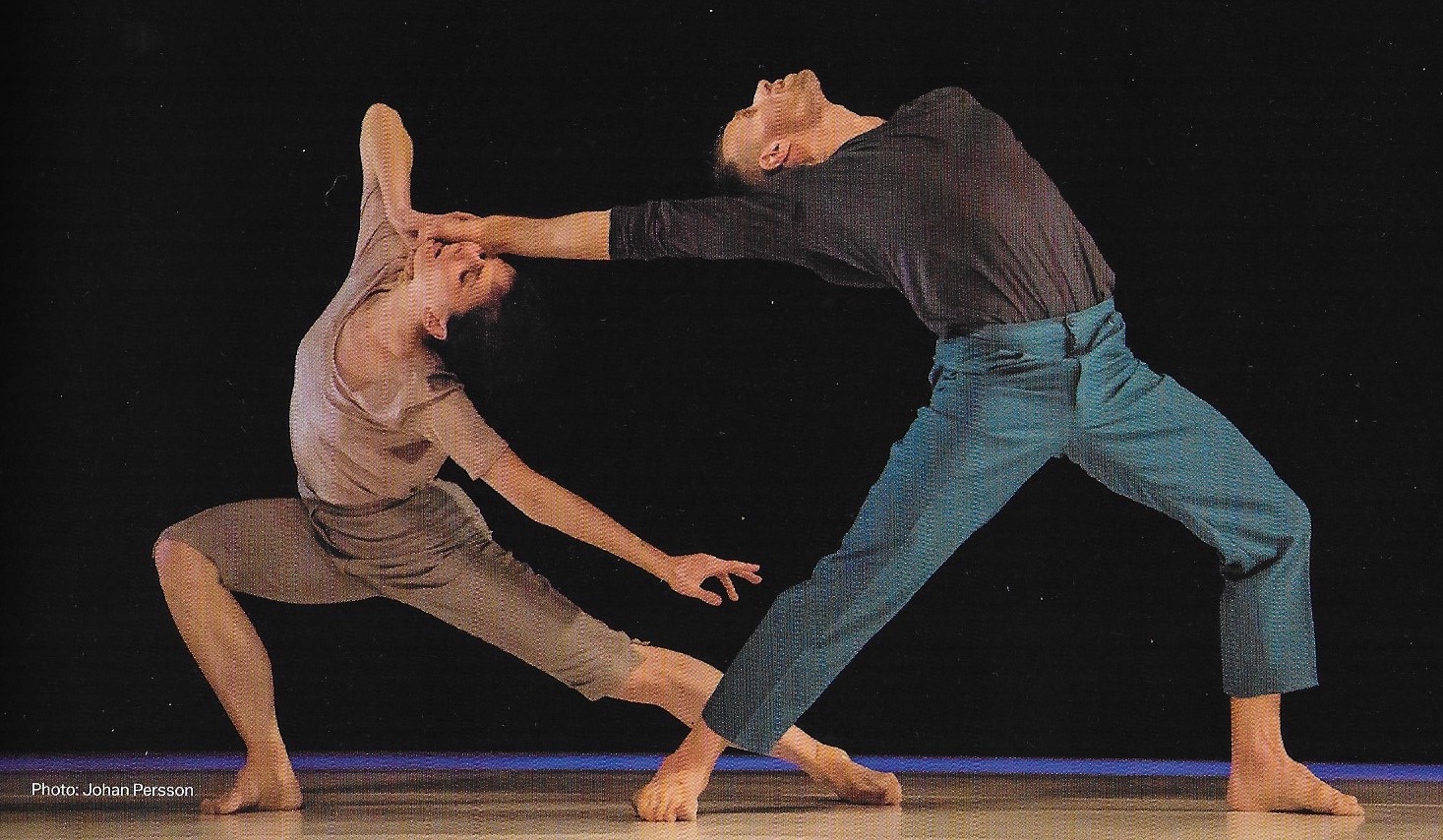

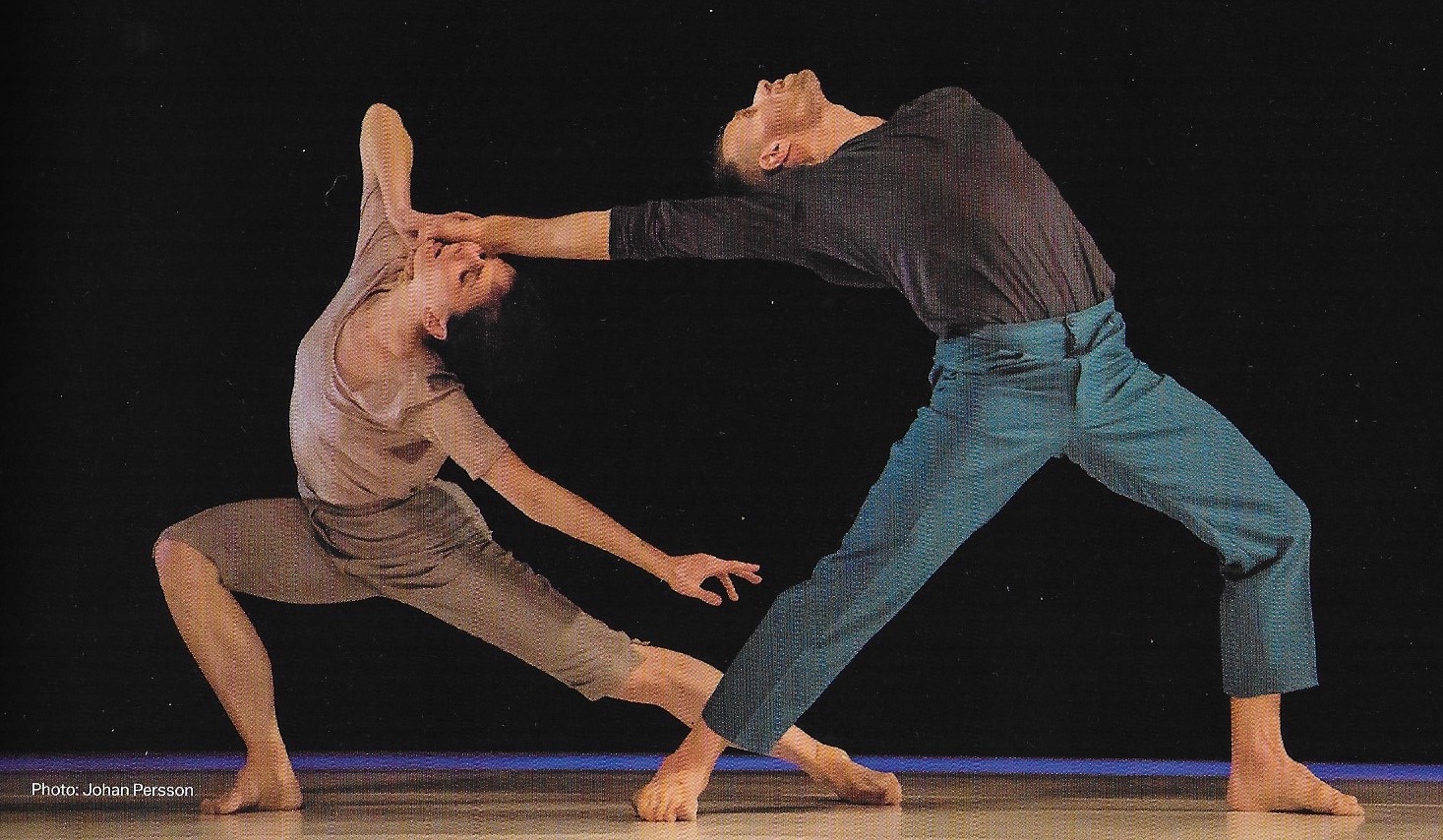

It’s a source of lingering personal regret that I haven’t spent more time at the ballet. Over the years, rare outings to see the Nederlands Dans Theater performing Twice (Sock It to Me) to James Brown’s music at Sadler’s Wells in 1970, Mikhail Baryshnikov and Gelsey Kirkland with American Ballet Theatre at the Coliseum in 1977, Twyla Tharp’s Nine Sinatra Songs at the Riverside Studios in 1994 and Matthew Bourne’s all-male Swan Lake at Sadler’s Wells in 1996 felt like journeys into a universe where the air was very different. This year’s adventure was another visit to Sadler’s Wells to see Natalia Osipova, the Bolshoi-trained principal dancer with the Royal Ballet, presenting Pure Dance, a programme of seven short pieces from different choreographers.

Among them was Six Years Later, created by Roy Assaf and danced by Osipova with Jason Kittelberger. Over the course of 22 minutes, it depicted the moods and responses of two people meeting after a lengthy estrangement: the range of gestures was considerable, from fond touches and entwinings to pushing, slapping and shoulder-barging. The first music was Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata, played straight but eventually treated (with great subtlety) by Deefly, twisting into a brief electronic episode that led to a big surprise: the strummed intro to “Reflections of My Life”, the 1969 hit by the Marmalade, the Scottish pop band who loitered successfully on the fringes of psychedelia. That in turn gave way to the final section and a third piece of music: Handel’s Dove Sei, Amato Bene? sung by Marilyn Horne. I found the emotional arc engrossing and the understated fluidity of the dancers’ movements compelling in their fluctuations between intimacy and distance. The real ballet critics were indifferent, so what do I know?

Beyond category

Amazing Grace: Aretha Franklin with James Cleveland and the Southern California Community Choir (dir. Sidney Pollack & Alan Elliott)

Live performances

1 Rhiannon Giddens / The Ensemble (HM Prison Wormwood Scrubs, Nov)

2 Royal Academy of Music alumni & soloists: Gil Evans’s Porgy & Bess (St John, Smith Square, Nov)

3 Binker Golding Quartet (Cockpit Theatre, Oct)

4 Nik Bärtsch / Sophie Clements (Barbican, Nov)

5 Soweto Kinch’s The Black Peril (Hackney EartH, Nov)

6 Bill Frisell + Harmony (Cadogan Hall, Oct)

7 Julia Hülsmann Quartet (Purcell Room, Nov)

8 Punkt.Vrt.Plastik (Vortex, Oct)

9 The Necks (Hackney EartH, May; St John, Bethnal Green, Oct)

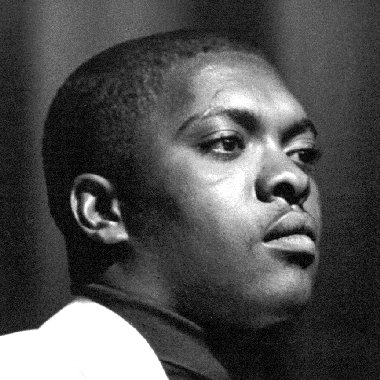

10 Louis Moholo-Moholo’s Five Blokes (Cafe Oto, Aug)

11 Lucia Cadotsch’s Speak Low (Purcell Room, Nov)

12 Kim Myhr (Kilden, Oslo, Sept)

13 Zbigniew Namysłowski (JazzCafé POSK, Dec)

14 Thurston Moore (Kick Scene, Oslo, Sept)

15 Erland Apneseth Trio (Spice of Life, Nov)

New albums

1 Terri Lyne Carrington + Social Science: Waiting Game (Motéma)

2 Matana Roberts: Coin Coin Chapter 4: Memphis (Constellation)

3 Tyshawn Sorey + Marilyn Crispell: The Adornment of Time (Pi)

4 SEED Ensemble: Driftglass (jazz:refreshed)

5 Christian Lillinger: Open Form for Society (Plaist Music)

6 Kronos Quartet / Terry Riley: Sun Rings (Nonesuch)

7 Solange: When I Get Home (Columbia)

8 Arve Henriksen: The Timeless Nowhere (Rune Grammofon)

9 Guillermo Klein & Los Guachos: Cristal (Sunnyside)

10 Isildurs Bane & Peter Hammill: In Amazonia (Ataraxia)

11 Michael Kiwanuka: Kiwanuka (Polydor)

12 Giovanni Guidi: Avec le temps (ECM)

13 P. P. Arnold: The New Adventures of P. P. Arnold (e*a*r)

14 Laura Jurd: Stepping Back, Jumping In (Edition)

15 Angélique Kidjo: Celia (Verve)

16 Art Ensemble of Chicago: We Are on the Edge (Pi)

17 Que Vola?: Que Vola? (Nø Førmat)

18 Beth Gibbons / Polish NRO / Penderecki: Górecki’s Symphony No 3 (Domino)

19 Allison Moorer: Blood (Autotelic)

20 Gebhard Ullmann’s Basement Research: Impromptus & Other Short Works (WhyPlayJazz)

21 Wadada Leo Smith: Rosa Parks / Pure Love (TUM)

22 Nérija: Blume (Domino)

23 Jaimie Branch: Fly or Die II: Bird Dogs of Paradise (International Anthem)

24 Lana Del Rey: NFR! (Interscope)

25 Corey Mwamba: Nth (Discus)

Archive & reissue albums

1 Various: This is Lowrider Soul (Kent)

2 John Coltrane: Blue World (Impulse)

3 Various: Further Perspectives & Distortions: An Encyclopedia of British Experimental and Avant-Garde Music 1976-84 (Cherry Red)

4 Wes Montgomery: Back on Indiana Avenue: The Carroll DeCamp Recordings (Resonance)

5 John Coltrane: Impressions / Graz 1962 (ezz-thetic)

6 Anne Briggs: Anne Briggs (Topic Treasures)

7 Jan Garbarek / Bobo Stenson Quartet: Witchi-Tai-To (ECM)

8 Various: Yesterday Has Gone: The Songs of Teddy Randazzo (Ace)

9 Bob Dylan: The Rolling Thunder Review / The 1975 Live Recordings (CBS Legacy)

10 Various: Dave Godin’s Deep Soul Treasures Vol 5 (Kent)

11 Johnny Burch Octet: Jazz Beat (Rhythm and Blues)

12 Nat King Cole: Hittin’ the Ramp (Resonance)

13 Various: Sacred Sounds: Dave Hamilton’s Raw Detroit Gospel 1969-74 (Kent)

14 Bob Dylan: Travelin’ Thru 1967-69 (CBS Legacy)

15 Don Cherry / Ed Blackwell: El Corazón (ECM)

Films

1 Varda by Agnès (dir. Agnès Varda)

2 The Image Book (dir. Jean Luc Godard)

3 The Irishman (dir. Martin Scorsese)

Music documentaries

1 Country Music (dir. Ken Burns)

2 Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool (dir. Stanley Nelson)

3 Hitsville: The Making of Motown (dir. Benjamin Turner & Gabe Turner)

Books about music

1 Booker T. Jones: Time Is Tight (Omnibus)

2 David Toop: Flutter Echo (Ecstatic Peace Library)

3 Emma John: Wayfaring Stranger (Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

4 James Pettifer: Meet You in Atlantic City (Signal)

5= Will Birch: Cruel to Be Kind: The Life & Music of Nick Lowe (Constable)

5= Ian Penman: It Gets Me Home, This Curving Track (Fitzcarraldo Editions)

Exhibitions

1 Ivon Hitchens (Garden Museum, London & Pallant House, Chichester)

2 Lee Krasner: Living Colour (Barbican)

3 Natalie Daoust: Korean Dreams (Beecroft Gallery, Southend)

4 Ed Ruscha (Tate Modern)

5 Various: Another Me (South Bank Arts Centre)