Mind on the Run

It was with regret that I had to leave Hull after only 24 hours of Mind on the Run, the weekend festival celebrating the life and work of Basil Kirchin, the visionary composer who spent three decades in the city, working in complete obscurity until his death in 2005, aged 77.

It was with regret that I had to leave Hull after only 24 hours of Mind on the Run, the weekend festival celebrating the life and work of Basil Kirchin, the visionary composer who spent three decades in the city, working in complete obscurity until his death in 2005, aged 77.

When the Guardian asked me to write a piece about the event, the first call I made was to Brian Eno. I had introduced the two men in 1973, while preparing the release of the second volume of Basil’s World Within Worlds on Island’s HELP label. Eno immediately recognised the value of his work with manipulated tapes of organic sounds, and more than 40 years later he was happy to talk about the impression it made.

The festival, held in the City Hall as part of Hull’s 2017 UK City of Culture programme, was quite brilliantly curated to include contributions from Matthew Herbert, Goldfrapp’s Will Gregory (with a contingent of the BBC Concert Orchestra, conducted by Clark Rundell), Wilco’s Jim O’Rourke, Bob Stanley and Pete Wiggs of Saint Etienne, Evan Parker with Adam Linson and Matt Wright of his Electro-Acoustic Ensemble and Ashley Wales and John Coxon of Spring Heel Jack, and a DJ set of Kirchin’s library music by Jerry Dammers.

On the first evening I heard a spirited set by a local five-piece band led by DJ Revenu (Liam van Rijn), heavy on imaginative electronics. That was followed by the High Llamas’ Sean O’Hagan with a piece inspired by several of Basil’s themes and performed by an nonet — including the outstanding harpist Serafina Steer — in a style that made me think of what might happen were Steve Reich to get it into his head to reinterpret those miniature tone poems that Brian Wilson used to drop into mid-period Beach Boys albums: things like “Fall Breaks and Back to Winter” from Smiley Smile and the title track of Pet Sounds. O’Hagan’s music was minimalist, lyrical, unhurried and unrhetorical, with a fragile charm. (Just after it had finished I told a friend that I was particularly attracted to the way the music felt, even now and then, as though it might be about to fall apart; during a conversation an hour or so later O’Hagan mentioned, unprompted, that this was precisely the effect he’d been after.)

I enjoyed taking part in one of the panel discussions, alongside Bob Stanley and Jonny Trunk, and listening to another that featured Matt Stephenson, co-director (with Alan Jones and Harriet Jones) of a 45-minute documentary film which did an excellent job of summarising Basil’s extraordinary life through interviews with those who had known him at various stages of his career. It also featured a wonderful film clip of the Ivor Kirchin Band in the early ’50s, with the leader’s young son as the featured drummer, from a time when dance band musicians wore cardigans and sensible slacks. (When someone in the audience likened Basil’s skin-pounding, cymbal-flaying antics to those of Animal from the Muppet Show, Matt was able to regale us with the priceless information that the real drummer of the Muppets had been the great session man Ronnie Verrell — who, in an earlier incarnation, had replaced the man who replaced Basil on the drum stool in Ivor’s band…)

Trunk, who has done so much over the past decade to create interest in Basil’s work, also mentioned that the handful of CDs released on his label represent no more than a glimpse of the tip of the iceberg. There is much more to come from the archive of Kirchin soundtracks and library music.

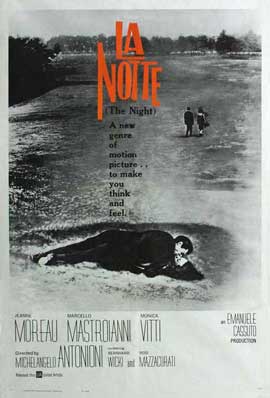

Among Basil’s credits was the score to The Abominable Dr Phibes, the truly bizarre 1971 British horror film in which Vincent Price played the eponymous villain, who celebrated his dreadful deeds by letting loose on a pipe organ. The film was screened on Friday night, with the figure of a caped Alexander Hawkins emerging through a gauze screen from time to time, playing the music live on the City Hall’s mighty organ: the third largest in England, it is said, and the possessor of a massive 64ft pipe which, if unleashed at full volume, would probably turn the Victorian building’s foundations to dust.

Before leaving Hull I also managed to creep into the soundcheck of Joe Acheson’s Hidden Orchestra (pictured above), and was beguiled by the grooves and textures of a band featuring two drummers, violin, cello, harp, trumpet and keyboards. If you want to know more about that performance, and others, read Tony Dudley-Evans’s report for the London Jazz News website.

It was interesting to discover how Hull, a victim first of the Luftwaffe and then of the Cod Wars, is making use of the opportunity to present a new face to those lured by the year of cultural events. There are five excellent Francis Bacons on temporary loan at the refurbished Ferens Gallery in the main square, which is dramatically spanned until March 18 by a 75-metre aluminium wind-turbine blade created by Nayan Kulkarni. An exhibition devoted to the story of COUM Transmissions, the renegade art collective founded in Hull in the early ’70s by Genesis P. Orridge, Cosey Fanni Tutti and others, is at the Humber Art Gallery in the streets of the former Fruit Market, where all sorts of hipster enterprises are springing up.

It’s not all great, of course. Take a bow, “Sir” Philip Green, for the vacant hulk of the striking early-’60s building until recently occupied by British Home Stores. But if you can imagine a cross between Copenhagen and Hoxton, that seems to be how Hull is attempting to reshape itself, and the audiences who flocked to Mind on the Run demonstrated the potential of this culture-led Humberside renaissance. I hadn’t been to the city since a single visit in 1965. Now I can’t wait to go back and do some more exploring.

There’s an hour-long Arena documentary about Chrissie Hynde on BBC4 this week. During a preview of a longer 90-minute version the other day, I remembered that what I always liked about her was the subtlety underlying the ferocious four-piece rock and roll attack of the Pretenders’ music. It was present in February 1979, when — at the urging of my friend and Melody Maker colleague Mark Williams — I went to see them at the Railway Arms in West Hampstead, a room once known as Klooks Kleek but then renamed the Moonlight Club.

There’s an hour-long Arena documentary about Chrissie Hynde on BBC4 this week. During a preview of a longer 90-minute version the other day, I remembered that what I always liked about her was the subtlety underlying the ferocious four-piece rock and roll attack of the Pretenders’ music. It was present in February 1979, when — at the urging of my friend and Melody Maker colleague Mark Williams — I went to see them at the Railway Arms in West Hampstead, a room once known as Klooks Kleek but then renamed the Moonlight Club.

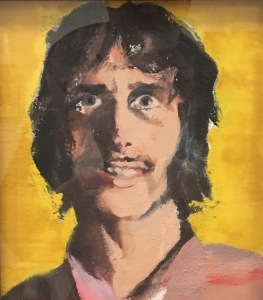

It came as a bit of a surprise to walk into a high-end London art gallery this week and discover a small portrait of Arthur Brown, the madcap rocker of the late ’60s, taking its place in an extensive exhibition of the work of the late English painter Michael Andrews.

It came as a bit of a surprise to walk into a high-end London art gallery this week and discover a small portrait of Arthur Brown, the madcap rocker of the late ’60s, taking its place in an extensive exhibition of the work of the late English painter Michael Andrews.