A night of two halves

Two great pianist-composers were at work within 400 yards of each other in Dalston last night. It was a tough call, so I compromised. The first half of the evening was spent at the Vortex in the company of the Christian Wallumrod Ensemble. The rest was devoted to a set by the Keith Tippett Octet at the Cafe Oto. Wallumrod was playing compositions from Outstairs, his latest ECM album, while Tippett was performing a recently commissioned suite, The Nine Dances of Patrick O’Gonogon. I was worried that by trying to catch both, I’d miss the best of either. But these were two such exalted experiences that by the end of the night I could only think what a extraordinary feeling it must be to create such music in your head and on paper and then have it brought to life by gifted and dedicated musicians.

Two great pianist-composers were at work within 400 yards of each other in Dalston last night. It was a tough call, so I compromised. The first half of the evening was spent at the Vortex in the company of the Christian Wallumrod Ensemble. The rest was devoted to a set by the Keith Tippett Octet at the Cafe Oto. Wallumrod was playing compositions from Outstairs, his latest ECM album, while Tippett was performing a recently commissioned suite, The Nine Dances of Patrick O’Gonogon. I was worried that by trying to catch both, I’d miss the best of either. But these were two such exalted experiences that by the end of the night I could only think what a extraordinary feeling it must be to create such music in your head and on paper and then have it brought to life by gifted and dedicated musicians.

Wallumrod’s six-piece band — with Eivind Lonning on trumpet, Espen Reinertsen on tenor, Gjermund Larsen on violin, viola and Hardanger fiddle, Tove Torngren on cello and Per Oddvar Johansen on drums — made a much greater impression on me in person than on record. Or perhaps it would be more sensible to say that they sent me back to Outstairs with a better understanding of what it is they’re doing. But I do think that in this case the live performance provides a vital extra dimension.

This is understated, reflective music, making great use of its Norwegian heritage (many of the themes sound as though they are inspired by folk songs), but the quiet power of the music’s physicality came as a surprise: when you actually witness Wallumrod gently pumping his portable harmonium, or Larsen playing soft-grained double-stops on the Hardanger fiddle, or Reinertsen discreetly using a slap-tongue technique to turn his saxophone into an extra percussion instrument, or Lonning brushing the mouthpiece across his lips as he exhales to produce shushing sounds and bringing out a four-rotary-valve piccolo trumpet to add a new texture, it helps to bring it to life. A long track from the album, called “Bunadsbangla”, featured Johansen using his hands and a slack-tuned bass drum to produce a kind of Scandinavian Bo Diddley rhythm behind a beautifully structured and voiced horns-and-strings line; I think I speak for everyone in the room when I say that we’d have been happy for that one to have gone on all night.

A quick dash down from Gillett Square to Ashwin Street meant that I missed only the first couple of minutes of Tippett’s octet set; the band was already in full roiling Mingusian mode. This was the third performance of the work, written for Keith’s terrific new London-based band, mostly consisting of recent graduates: trombonists Kieran McLeod and Rob Harvey, saxophonists Sam Mayne and James Gardiner-Bateman, bassist Tom McCredie and the veteran drummer Peter Fairclough, with Ruben Fowler depping for Fulvio Sigurta on trumpet and flugelhorn. For me, the format of an octet often seems to locate the perfect middle ground between the flexibility of a smaller horns-and-rhythm combo and the mass and strength of a conventional big band. Tippett, who is writing and playing with a greater range and eloquence than at any time in his 45-year career, knows how best to exploit its potential to the full.

The nine movements were full of contrast, varying in mood from raucous shout-ups to a tiny, exquisite piano coda, enfolding a hymn-like horn chorale framing short unaccompanied piano improvisations, a kind of jig, and something that roared along at 80 bars per minute (that’s 320 of your “beats”, children), a tempo at which it is hard enough to think, never mind improvise coherently. I particularly loved Sam Mayne’s show-stopping alto, a flugel solo on which Fowler reminded me of the late, great Shake Keane, McLeod’s agile, thoughtful trombone, and the impressive maturity of McCredie, who coped nimbly with the demanding score but was always playing with his heart open. A sense of passion characterised the whole band as they negotiated a composition in which Tippett’s defining streak of lyricism never flagged, even when the music’s operating temperature was at its height.

They’ll be back in Dalston to play the piece again on April 11, this time at the Vortex. Keith is still waiting to hear whether the producers of the BBC’s Jazz on 3 are interested in broadcasting the piece. When he asked them, the response was that they wanted him to send a tape. After four decades in which his consistently distinguished work has brought him acclaim around the world, from Italy and France to Russia and India and South Africa, the gatekeepers of Britain’s jazz principal broadcasting outlet seem to be expecting him to audition. If he felt insulted by such a response, it would be hardly surprising or unjustified.

Last night, anyway, Wallumrod and Tippett — who share a gift for bringing the lessons learnt from jazz to bear on their respective native cultures — received the sort of response they deserve: sustained ovations from attentive listeners who know great music when they hear it, and are properly grateful for the experience.

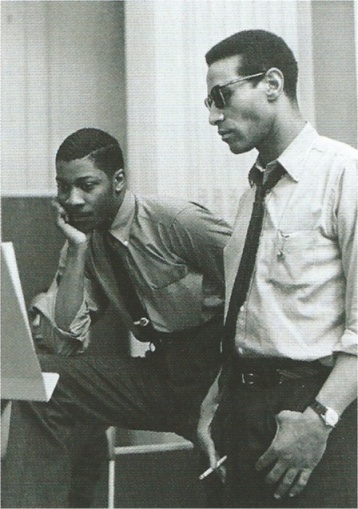

* The photograph of the Christian Wallumrod Ensemble was taken by Christopher Tribble at Kings Place on their visit to London last year.