Motown part 2 (of 3): The white guy’s story

The name of Barney Ales became a familiar one to those who took a close interest in the evolution of Motown Records in the 1960s. Ales didn’t sing, or write songs, or produce sessions. He wasn’t a musician or a choreographer or a voice coach. He was the guy hired by Berry Gordy Jr in 1961 as national sales manager and promotion director. And now he is the co-author, with the music historian Adam White, of Motown: The Sound of Young America, a lavishly produced history of the label.

Ales had worked for Capitol Records before joining Motown at the age of 27. His job was to get the records played on the radio and to ensure not just that they were distributed efficiently to record stores around the country but that the invoices got paid. Almost as much as the quality of the music, that was the secret of Gordy’s operation: business had to be taken care of with a different attitude from that of most black-owned labels. He needed someone who could talk to white disc jockeys and record distributors without the barrier, conscious or unconscious, of race.

One can assume that, having worked with the founder almost from the beginning and ending up as a vice-president before leaving in 1978, Ales knows a few secrets behind Gordy’s struggle to establish the label and extend its success beyond the boundaries of black America. Perhaps those with fond memories of Number One With a Bullet, the novelised version of the Motown story written by Elaine Jesmer, a former publicist, and never republished after its original appearance in 1974, will come to Ales’s memoir hoping for true-life confessions. That would be a mistake. This is a version of the tale that passes lightly over the darker episodes, while containing much detail that will be useful to those wanting to know more about Gordy’s triumph.

There are many books about Motown, including the autobiographies of Gordy, Smokey Robinson, Otis Williams and Mary Wilson. My own favourite is one of the more modest efforts: Susan Whitall’s Women of Motown, an oral history based on interviews with Martha Reeves, Claudette Robinson, Kim Weston, Brenda Holloway, Mable John, Carolyn “Cal” Gill and others, published in the US by Avon Books in 1998. White and Ales give us a view from a different perspective, and a valuable one.

The narrative begins in an interestingly unorthodox way with a long and well illustrated account of the Detroit riot of 1967, which devastated clubs and record stores as well as homes and other businesses. It came perilously close to the Motown headquarters on West Grand Boulevard, where bullet holes in the flower pots outside the entrance were the only sign of damage to what, with gross income of $20m the previous year, was on the way to becoming America’s biggest black-owned business. The significance is that, only a month after the fires in the ghetto had finally been extinguished, Gordy and Ales had the courage to go ahead with Motown’s first-ever national sales conference, with a gala concert at the Roostertail Club on the banks of the Detroit River featuring the Supremes, Gladys Knight, Stevie Wonder, Chris Clark and the Spinners. Fifteen new albums were announced at the conference; on the day of the launch, the sales department was able to count a record $4m in orders, or 20 per cent of the preceding year’s revenue.

That’s typical of the kind of detail Ales provides. His description of his dealings with Morris Levy, the heavily Mob-connected boss of Roulette Records, contains the fascinating story of how Mary Wells’ “My Guy” was bootlegged in the New York area by Gordy’s ex-wife, Raynoma Liles, who had moved to the city to open an office for the company’s song-publishing division, only to have the funding cut off by her former husband. As she told it in her own autobiography (Berry, Me and Motown, published in the US by Contemporary Books in 1990), she had 5,000 copies pressed up and sold them to a distributor for 50 cents apiece in order to raise the money to keep the office open. It was unfortunate for Liles — an important figure in the early days of the company, as an arranger and musical director — that by selling counterfeit copies of the Wells hit, she was depriving Levy of income. Her own account does not mention him, perhaps because he was still alive when she wrote it.

All this, and much more, is extremely well told and to be enjoyed alongside the wonderful illustrations, including contact sheets, album jackets, picture sleeves and advertising material in this large-format publication. My favourite of the many fabulous photographs is one by Bruce Davidson, the great Magnum photographer, who catches the Supremes backstage in New York in 1965, sitting alongside each other in their dressing room, bathed in pink light, surrounded by make-up pots, perfume bottles and ashtrays. Davidson shoots from above and behind the three women, catching their reflections: Flo Ballard using a tissue to blot her mascara and Mary Wilson touching up her hair, both sharing a single mirror, while Diana Ross, with her own individual mirror, stares straight into his lens.

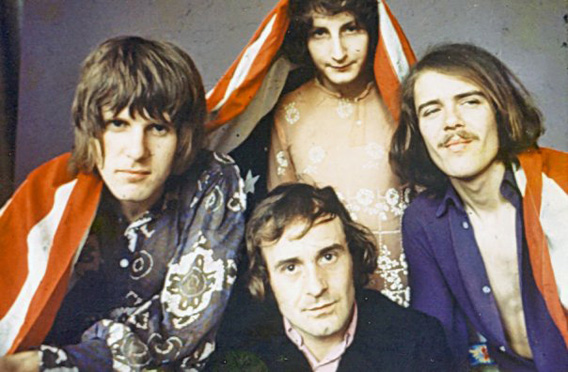

* In the photograph above, Barney Ales (standing, extreme left) is hosting a group of Detroit radio personalities at the Roostertail Club. It can be found in Motown: The Sound of Young America, which is published by Thames & Hudson, price £39.95.

It’s 14 years since Jessica Ferber, who had just graduated in sociology and photography from the University of Vermont, was handed a few boxes of photographic prints and negatives and other bits and pieces left by a recently deceased resident of a homeless shelter. She was asked if she wanted to do something with them. They would occupy much of her time for the next decade as she sorted through the material, began the painstaking process of restoration, and then raised funds via Kickstarter to complete the work and to secure publication in book form.

It’s 14 years since Jessica Ferber, who had just graduated in sociology and photography from the University of Vermont, was handed a few boxes of photographic prints and negatives and other bits and pieces left by a recently deceased resident of a homeless shelter. She was asked if she wanted to do something with them. They would occupy much of her time for the next decade as she sorted through the material, began the painstaking process of restoration, and then raised funds via Kickstarter to complete the work and to secure publication in book form.

Keith Emerson died the other day, aged 71, apparently by his own hand. According to Mari Kawaguchi, his partner of more than 20 years, he had been thrown into a depression by the effect of nerve damage on his ability to play his keyboard instruments, with a series of concerts in prospect. Whatever one’s opinion of Emerson’s work, it is extraordinarily sad that his career should seemingly have ended in that particular form of defeat. Of one thing there was no doubt: his love of music.

Keith Emerson died the other day, aged 71, apparently by his own hand. According to Mari Kawaguchi, his partner of more than 20 years, he had been thrown into a depression by the effect of nerve damage on his ability to play his keyboard instruments, with a series of concerts in prospect. Whatever one’s opinion of Emerson’s work, it is extraordinarily sad that his career should seemingly have ended in that particular form of defeat. Of one thing there was no doubt: his love of music. Forty five summers ago, George Martin granted me a long interview for the Melody Maker. It was a very enjoyable experience: he was most courteous of men, and his answers were full of fascinating detail, with the occasional gentle indiscretion. He spoke in some depth about his experience of working with the Beatles, all the way from “Love Me Do” to Abbey Road, and the result was published in three parts, on August 21 and 28 and September 4, 1971. Lennon and McCartney were at war with each other that year, and some of what he said got up John’s sensitive nose, provoking a couple of letters from New York, the first of which you can see above. But when I asked Martin about the making of “A Day in the Life”, he responded with a very thorough and interesting description, giving a vivid snapshot of the creative relationship between the producer and the four young men he always referred to as “the boys”, a partnership based on his willingness to entertain their interest in taking risks and their respect for his experience and integrity. Had he, I asked, been responsible — as rumour then had it — for sweeping up several seemingly disconnected musical episodes from the studio floor and sticking them together to create a masterpiece?

Forty five summers ago, George Martin granted me a long interview for the Melody Maker. It was a very enjoyable experience: he was most courteous of men, and his answers were full of fascinating detail, with the occasional gentle indiscretion. He spoke in some depth about his experience of working with the Beatles, all the way from “Love Me Do” to Abbey Road, and the result was published in three parts, on August 21 and 28 and September 4, 1971. Lennon and McCartney were at war with each other that year, and some of what he said got up John’s sensitive nose, provoking a couple of letters from New York, the first of which you can see above. But when I asked Martin about the making of “A Day in the Life”, he responded with a very thorough and interesting description, giving a vivid snapshot of the creative relationship between the producer and the four young men he always referred to as “the boys”, a partnership based on his willingness to entertain their interest in taking risks and their respect for his experience and integrity. Had he, I asked, been responsible — as rumour then had it — for sweeping up several seemingly disconnected musical episodes from the studio floor and sticking them together to create a masterpiece? It’s pretty strange that the man best known for “Ahab the Arab”, “Bridget the Midget” and “Everything is Beautiful” should have written and recorded one of the most striking protest songs of the 1960s. That, at least, is how I’ve always thought of Ray Stevens’ “Mr Businessman”.

It’s pretty strange that the man best known for “Ahab the Arab”, “Bridget the Midget” and “Everything is Beautiful” should have written and recorded one of the most striking protest songs of the 1960s. That, at least, is how I’ve always thought of Ray Stevens’ “Mr Businessman”. It’s 30 years today since Richard Manuel took his own life in his room at the Quality Inn motel, Winter Park, Florida, a few hours after a gig. Born 42 years earlier in Stratford, Ontario, Manuel was both the owner of one of the most emotionally direct and affecting voices in the history of rock and roll and a member of what had been, by common agreement of most of the people I know, its finest band.

It’s 30 years today since Richard Manuel took his own life in his room at the Quality Inn motel, Winter Park, Florida, a few hours after a gig. Born 42 years earlier in Stratford, Ontario, Manuel was both the owner of one of the most emotionally direct and affecting voices in the history of rock and roll and a member of what had been, by common agreement of most of the people I know, its finest band. Jez Nelson’s monthly Jazz in the Round nights at the Cockpit Theatre in Marylebone are as good a way to hear improvised music in London as anyone has yet devised. A couple of hundred listeners settle themselves down in mini-bleachers on all four sides of the floor, where the musicians set up to face each other, creating an unusual degree of intimacy radiating through 360 degrees. As a member of Empirical — I think it was Nathaniel Facey, the alto saxophonist — told last night’s audience, it makes you play differently. In a good way.

Jez Nelson’s monthly Jazz in the Round nights at the Cockpit Theatre in Marylebone are as good a way to hear improvised music in London as anyone has yet devised. A couple of hundred listeners settle themselves down in mini-bleachers on all four sides of the floor, where the musicians set up to face each other, creating an unusual degree of intimacy radiating through 360 degrees. As a member of Empirical — I think it was Nathaniel Facey, the alto saxophonist — told last night’s audience, it makes you play differently. In a good way.