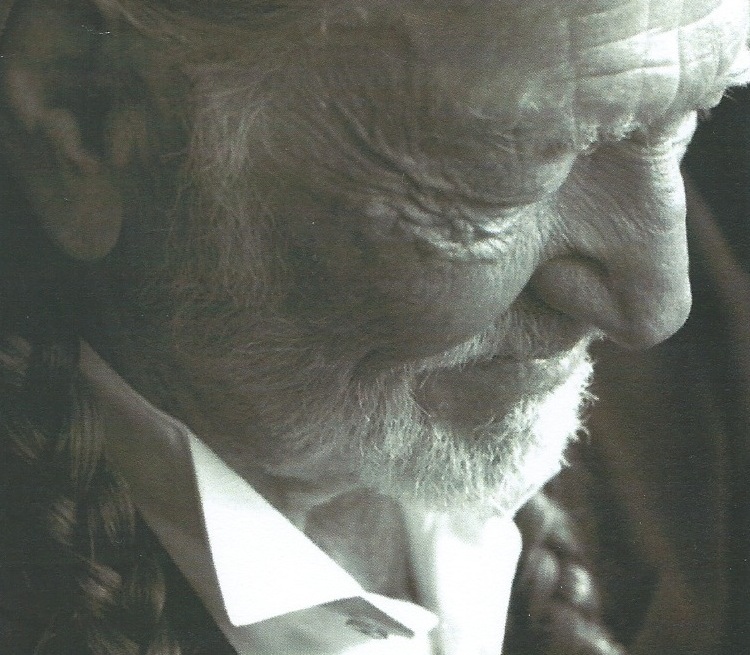

Lou Reed 1942-2013 (2)

You might feel you’ve read enough about Lou Reed in the last couple of days (and here is my Guardian obituary), but here are a few last thoughts.

1.

You’ll have heard a lot about how difficult it was to interview Lou successfully. Without wishing to criticise my colleagues, it always seemed to me that the journalists who had a hard time with him were the ones who felt he owed them answers to questions he had already been asked a million times. I mean, “Were you really on heroin when you wrote ‘Heroin’?” — asked 40 years after the fact — was unlikely to elicit a positive reaction.

Not to say that he was a little ray of sunshine even in the most propitious circumstances. But, like a lot of artists, he preferred contemplating the present and anticipating the future to raking over the past. He was proud of the early stuff, but you can tell just by reading the later interviews that he didn’t want to spend his life discussing it. He usually responded well to people who showed that they had taken the trouble to keep track of what he had been up to in the years since the achievements that brought him his legendary status. If an interviewer wanted to talk about Ornette Coleman (as Bob Elms did on Radio London) or Tibetan philosophy (as Mick Brown did in the Telegraph), he was likely to show genuine enthusiasm and engage in something resembling a real dialogue.

I suppose I was lucky to get to him before the period that began when Transformer and “Walk on the Wild Side” made him a hot act, the point at which large numbers of reporters started to interrogate him. He hadn’t yet met David Bowie — and might not even have heard of him — when I sat down with him at the Inn on the Park in London one day in mid-January, 1972.

He was in London to record his first solo album, accompanied by his producer, Richard Robinson, and Richard’s wife, Lisa, then the New York correspondent of Disc and Music Echo. The Robinsons were friends of mine and they knew I was a Velvet Underground fan of long standing, and soon after their arrival we all had lunch together at the hotel. Lou was quiet and a little preoccupied but perfectly good company.

A few weeks later, after they’d recorded and mixed most of the album with a very heterogeneous bunch of English musicians at Morgan Studios in Willesden (where Rod Stewart had cut Every Picture Tells a Story), I sat down with Lou in his room to listen to some of the near-completed tracks, with the intention of writing a piece for the Melody Maker. It was a very congenial experience. He was so relaxed and willing to talk about his past that when I read the piece now, I feel guilty that I didn’t convey more of his thoughts about the new material. As things turned out, the album — called Lou Reed — created barely a ripple of public interest; soon to be overshadowed by Transformer and his liaison with Bowie, it acquired the dismal aura of a failed project. Give it a proper listen today, however, and you’ll find that “Wild Child”, “Love Makes You Feel” and “Ride into the Sun” are more than worth their place in his canon.

At one point I asked him about the Velvets’ third album, and if he would be willing to support my theory, aired in a review when it came out in 1969, that its 10 songs constituted a single narrative. He seemed delighted. “I’ve never known whether it worked for other people,” he said. “I’ve always written with the idea of putting songs into concepts so that they relate to one another. I always thought of these like chapters in a novel, and that if you played the first three albums all in order, it would really make huge total sense. No one ever seemed to pick up on that, and why should they? I don’t put out that many albums anyway, so by the time Chapter Three arrived, you had to go running back to the archives to find where Chapter Two left off.”

When the song on Lou Reed called “Berlin” mutated, a couple of years later, into the entire album called Berlin, with its cast of characters and single continuous and coherent narrative, he seemed to have achieved his ambition to make a rock and roll album that worked like a novel.

2.

No doubt there will be a great deal of reassessment of Reed’s work in the coming years. Given the way the once-despised Berlin was rehabilitated, don’t bet against something similar happening to Lulu — his recent album with Metallica, even more voceriferously despised by US critics — one day. I’ve been listening to it over the past 24 hours, and it seems to me that anyone who claims to adore the harsher moments of White Light/White Heat yet dismisses this one needs to have a serious rethink.

A more likely beneficiary, however, could be Songs for Drella, the album he made with John Cale for Sire in 1990 as a farewell to Andy Warhol, their former patron. Originally performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, it’s a biography in music, beginning with Warhol’s origins as a youthful misfit in Pittsburgh and tracing the story through his early days as an advertising artist and his rise to prominence as a succes de scandale in the New York art world of the 1960s to Valerie Solanas’s attempt to kill him and his eventual death from a heart attack following gallbladder surgery in 1987.

Reed and Cale were close to Warhol, but their view of his world is as clear-sighted and illuminating as it is generous and affectionate. Musically, it gains impact from its sense of intimacy: the instrumentation is restricted to Reed’s guitars and Cale’s various keyboards and viola. They both sing, the simplicity of the surroundings highlighting the restrained emotion in their voices. There’s a lot of contrast, effectively employed, like the jump from the elegance of Cale accompanied by strings on the delicate “Style It Takes” to Reed’s rapid-fire delivery over the chattering keyboard and buzz-saw guitar of “Work”, but the whole song-cycle coheres beautifully, forming a perceptive and touching tribute to a man who played a significant role in their careers. It’s easy to imagine its reputation increasing as the years pass.

3.

If you don’t already know it, try to hear Lou’s version of Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman’s “This Magic Moment”, included in a CD called Till the Night Is Gone: A Tribute to Doc Pomus, issued in 1998 by Forward/Rhino. The album features a stellar cast — Dylan, B.B. King, Brian Wilson, Irma Thomas, Los Lobos, Roseanne Cash, Dr John, Aaron Neville, Dion, Solomon Burke, etc — but his track is a standout. Originally a Top 20 hit for the Drifters in 1960, it allows him to demonstrate both his deep affection for R&B and his gift for stripped-down rock and roll, his two guitar parts — one skirling, the other snarling — accompanied by Fernando Saunders on bass and George Recile on drums. And he really was among the most unorthodox and creative of rock guitarists, a fact often overlooked in the desire to acclaim his more headline-friendly characteristics.