Tammi Terrell 1945-1970

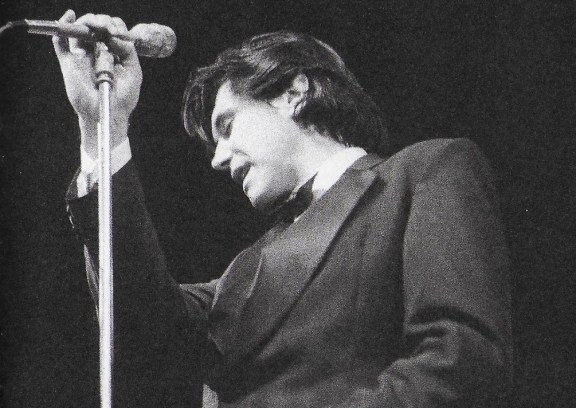

Fifty years ago, on March 16, 1970, Tammi Terrell died at the age of 24, following several operations for brain cancer. Her illness had become dramatically apparent on the night, two and a half years earlier, when she collapsed into the arms of her singing partner, Marvin Gaye, on stage at the Hampton-Sydney College in Virginia. Earlier in 1967 the teaming with Gaye had finally given her success: three consecutive Top 20 hits with “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough”, “Your Precious Love” and “If I Could Build My World Around You”. There would be others in the agonising months between that first collapse and her death, including “If This World Were Mine”, “Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing” and “You’re All I Need to Get By”.

Neither a diva nor a natural soul sister, Tammi Terrell was hard for the A&R and songwriting teams at Motown Records to place as a solo artist. She turned out to be a girlfriend, which is why her records with Gaye were so effective.

It’s also how she is remembered, which makes it interesting to listen to Come On and See Me: The Complete Solo Collections, a two-CD anthology compiled 10 years ago by Harry Weinger for the Hip-O Select label. Adding pre-Motown material and rare, unreleased and live tracks from her Hitsville USA days to her one solo album (titled Irresistible), the collection leaves the listener wondering why she never achieved success in her own right.

Born Thomasina Montgomery to a middle-class Philadelphia family, she won a talent contest at the age of 11. Four years later the New York producer Luther Dixon signed her to Scepter Records, whose headline artists included the Shirelles and Dionne Warwick. Scepter shared Motown’s habit of rotating the same backing track among different singers until a combination clicked. So it’s interesting to hear Tammy Montgomery — as she had become — singing to the same track of Dixon’s “If You See Bill” that would turn up on Warwick’s debut album two years later, and revoicing the Shirelles’ “Make the Night a Little Longer”, written by Gerry Goffin and Carole King. There’s also a version of Burt Bacharach and Bob Hilliard’s “Sinner’s Devotion” which virtually defines Scepter’s variation on the uptown soul sound.

In 1963 she joined James Brown’s touring company and recorded a couple of his songs, “I Cried” and “If You Don’t Think”, for his Try Me label. The association was ended, according to Daphne Brooks’ excellent sleeve note, when her family discovered that their daughter was in an abusive relationship with Brown. Back in New York she recorded four sides for Chess Records’ Checker subsidiary with the producer Bert Berns, including “If I Would Marry You”, a co-composition by the singer and the producer in which they attempt to reproduce the magic of Inez and Charlie Foxx’s “Mockingbird”. The anthology includes an unreleased version of the song in which Tammy is joined at the microphone by Jimmy Radcliffe (he of “Long After Tonight Is All Over”) in a pre-echo of her work with Gaye.

Tammy was performing at Detroit’s 20 Grand nightclub, a favourite of Motown artists and staff, when she was heard by Berry Gordy Jr, who promptly signed her up — maybe as a replacement for the recently departed Mary Wells, his first female star, perhaps glimpsing the potential to develop a similar girlish sweetness — and renamed her Tammi Terrell. She was put to work with the producer/songwriter team of the experienced Harvey Fuqua and the novice Johnny Bristol, but first two years with the label, 1965 and 1966, yielded only two singles: “I Can’t Believe That You Love Me” and “Come On and See Me”. Today it seems bizarre that neither was a hit — particularly the second of them, with its irresistible syncopated chorus and every other element of the classic mid-’60s Motown sound present and correct.

The 18 rare, unissued and unfinished studio tracks on the second disc contain plenty of further examples of Motown in its prime years, while demonstrating the efforts being made to establish an identity. On the driving “I Gotta Find a Way (To Get You Back)” the producer Norman Whitfield seems to be trying to cast her as the new Martha Reeves. She was even sent to Los Angeles to record “Oh How I’d Miss You” with Hal Davis and Frank Wilson and an unidentified male singer joining the chorus — another hint of things to come. A song called “Lone Lonely Town”, written and produced by Mickey Gentile and Mickey Stevenson, became a Northern Soul favourite when it escaped the vaults many years later. “Give In, You Just Can’t Win”, another Fuqua/Bristol effort, and “All I Do Is Think About You”, co-written (and later re-recorded) by Stevie Wonder, are such perfect Motown records that it’s hard to believe they didn’t make it past the label’s weekly quality control meeting.

Her time at Motown, however, was disrupted by an affair with David Ruffin, again accompanied by allegations of abuse. In Susan Whitall’s valuable oral history Women of Motown, Brenda Holloway remembered the woman she called her best friend at the label: “She was a very, very sad, sad little person who was looking for love, and she paid the price for the love she didn’t have. She was a beautiful woman, but she was looking for love and she paid the price. Maybe she felt guilty because of her looks. They feel guilty because they can get anyone they want. But once you get them, is this what you really want? After you find out about the person you’ve attracted, you can’t shake loose. And she just got attached to the wrong people. She was vulnerable because her heart was exposed.”

Before the hits with Gaye – written by Nick Ashford and Valerie Simpson — finally brought her into focus, Motown had certainly put some promotional muscle behind her solo career. The Hip-O Select set finishes with a recording made of part of her showcase appearance at the Roostertail, another popular Detroit night spot, on September 19, 1966. By opening with Lerner and Lowe’s “Almost Like Being in Love”, from the 1940s musical Brigadoon, she reminds us of Gordy’s desire to guide his female singers towards the middle of the road. A medley including “What a Difference a Day Makes”, “Runnin’ Out of Fools” and “Baby Love”, saluting Dinah Washington, Aretha Franklin and her labelmate Diana Ross, is also intended to show her versatility. But the live versions of her first two singles have the Motown road band and backing singers operating at full power behind a 21-year-old Tammi Terrell whose poised delivery suggests what she might have achieved, given time.