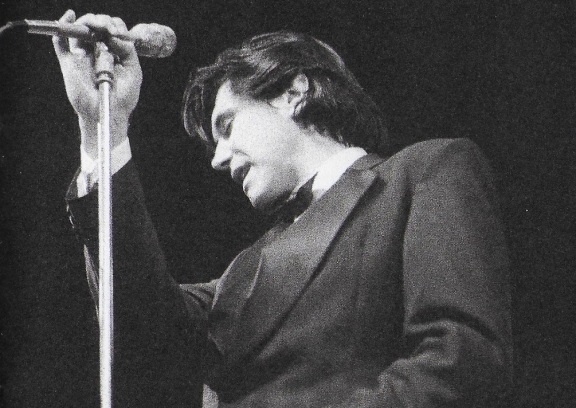

Revisiting Eric Burdon

The memory of hearing Eric Burdon sing “House of the Rising Sun” with the Animals at the Odeon, Nottingham one summer night in 1964 — a week or two before it was released as a single — is as clear as yesterday. In some ways it was the precursor of a new kind of rock music. But to Burdon, as he explains in a new biographical documentary shown on BBC4 this weekend, it meant something different. When Alan Price, the group’s organist, took credit for the words (traditional) and the arrangement (borrowed by Bob Dylan from Dave Van Ronk), it damaged the singer’s faith in music as a collective endeavour: all for one and one for all.

Luckily, although the animosity towards Price is still burning fiercely more than half a century later, it didn’t cause Burdon to end his career. As Patti Smith, Bruce Springsteen and Steve Van Zandt testify in the programme, post-Price Animals hits like “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” and “It’s My Life” were nothing short of inspirational to the next generation. But as the decades went by, there was always a sense that Burdon, one of the great English R&B voices of the ’60s, never quite recaptured the same level of fulfilment.

The hour-long Eric Burdon: Rock and Roll Animal, directed by Hannes Rossacher, is a co-production by the BBC with ZDF and Arte. There are interesting passages on his apprenticeship at the Club A Go Go in Newcastle, his relationship with Jimi Hendrix, his time in San Francisco and his collaboration with War — who dumped him, he claims, because he was the white guy in the band (there was actually another, the harmonica-player Lee Oskar). There’s quite a lot of stuff about his 50-odd years of living in California, and we see him cruising through the desert in some ’70s gas-guzzler or other.

We leave him, weathered but unbowed, with his new American band — new in 2018, anyway, when the film was made — preparing to record an album. He sings “Across the Borderline”, the great song written in 1981 by Ry Cooder with Jim Dickinson and John Hiatt for the soundtrack of Tony Richardson’s The Border, a film about immigrants. Originally sung by Freddie Fender, it subsequently found its way into the repertoires of Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Jackson Browne and Willie Nelson. It suits Eric Burdon just fine.

* The screen-grab is from Eric Burdon: Rock and Roll Animal, which can be watched on BBC iPlayer until the end of March.