Blissful company

What’s so funny about peace, love and understanding? The fiftieth anniversary of the Summer of Love might be a good time to reconsider Nick Lowe’s rhetorical demand. In these harshly polarised times, we might look back with wonder on a brief era when a young generation commanded the world’s headlines with a philosophy that was essentially generous, outward-looking and benevolent.

What’s so funny about peace, love and understanding? The fiftieth anniversary of the Summer of Love might be a good time to reconsider Nick Lowe’s rhetorical demand. In these harshly polarised times, we might look back with wonder on a brief era when a young generation commanded the world’s headlines with a philosophy that was essentially generous, outward-looking and benevolent.

Quintessence were purveyors of Indian sounds and philosophies to the heads of Ladbroke Grove between 1969 and 1971. A lot of their material, some of it previously unreleased, has been unearthed in recent years on several albums compiled for the Hux label by the author and researcher Colin Harper, including a terrific live recording of their memorable 1970 concert at St Pancras Town Hall, released in 2009 as Cosmic Energy. Now their first three studio albums, recorded for Island, are compiled on Move into the Light, a two-CD set on Cherry Red’s Esoteric imprint.

Naturally, being an underground band, they were featured in IT and ZigZag, but they had their fans in the straight music press, too. I wrote favourably about them in the Melody Maker at the time, as did my friend Rob Partridge in Record Mirror. I remember their flautist and leader, Raja Ram (born Ron Rothfield in Australia), telling me that he’d studied in New York with the great jazz pianist Lennie Tristano: “A dollar a minute, but believe me it was worth it.” Their singer, Shiva, another Australian, had been a star back home leading a blues-rock band under his birth name, Phil Jones. The excellent drummer, Jake Milton, was Canadian. Alan Mostert, the lead guitarist, was from Mauritius. The bass guitarist, Shambhu (Richard Vaughan), was American. Their rhythm guitarist, Maha Dev (Dave Codling), was British. The band’s manager, the somewhat intense Stanley Barr, was a poet.

They became regulars at places like the Roundhouse, Friars in Aylesbury, the Temple (formerly the Flamingo) in Soho and elsewhere before graduating to bigger venues around the country, including the Albert Hall, which they filled in December 1971. A disagreement over a deal to release their album in the United States provoked a rupture with Island, but they were already starting to disintegrate by the time they moved on to RCA, with whom they released their fourth and fifth albums in 1972.

The beatific preachiness of their lyrics would draw the odd chuckle today, and there’s a certain amount of 1970-style clumpiness in the rhythms, but much of the music on the three albums making up Move into the Light (In Blissful Company, Quintessence and Dive Deep, all produced by John Barham), still sounds pretty good. Taking their cue from the Grateful Dead and Quicksilver Messenger Service, they mixed songs and extended jams as effectively as any band in Britain at the time, with confident flute and guitar solos.

But how things have changed in the part of London they once called home. “We’re getting it straight on Notting Hill Gate / We all sit around and meditate,” Shiva sings on a track from the first album. The hedge fund managers and investment bankers who nowadays populate the once shabby and affordable streets of London W11 might have their own variant on that refrain: “We’re getting it straight on Notting Hill Gate / We sit around and rig the LIBOR rate…”

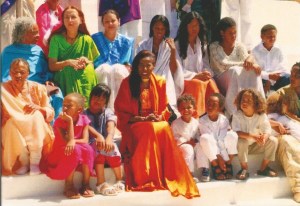

There’s more peace, love and understanding on The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane, the first volume in a series on the Luaka Bop label titled “World Spirituality Classics”. This is music made by John Coltrane’s widow for semi-private circulation after ending her recording career with commercial labels and taking herself off to become the spiritual director of an ashram in Malibu, California, where she was known as Turiyasangitananda.

Between 1982 and 1995 she made four cassettes available to initiates: Turiya Sings, Divine Songs, Infinite Chants and Glorious Chants. The Luaka Bop CD is a compilation drawn from those recordings (the vinyl edition, a double album, has two extra tracks), featuring individual and choral chants, based on drones created by various keyboards — harmonium, organ, synthesiser — and harp, strings, sitars and tamburas, sometimes accompanied by hand percussion. The result achieves a quietly glowing blend of South Indian timbres and tonalities and African American spirituals.

The opening track, “Om Rama”, gets straight under your skin, synths whooshing and skirling around an infectious group chant that changes gear and develops a gospel-music edge, featuring an impassioned male lead singer who reminds me a little of Philippé Wynne. There’s some poised solo singing — by Alice Coltrane herself, I’d guess — on “Rama Rama”, and “Er Ra” is a short piece for her solo harp, almost koto-like in its delicacy, and voice. A 10-minute version of “Journey in Satchidananda” (which had been the title track of one of her Impulse albums in 1970) is almost as stately and uplifting as one of her late husband’s musical prayers. She died in 2007, aged 69, having outlived John by 40 years. But when you listen to this music it’s easy to convince yourself that neither of them is really gone.

A few years ago, in response to a realisation that a phenomenon was under way, I reorganised my jazz CDs to provide a special alphabeticised section for piano trios. There were a lot of them, going back to Teddy Wilson, Art Tatum, Bud Powell, Thelonious Monk and Bill Evans and incorporating Herbie Nichols, Elmo Hope, René Urtreger, Mike Taylor, Martial Solal, Howard Riley, Bobo Stenson and many others, and the number grew fast as the influence of Keith Jarrett, Brad Mehldau, the Necks, EST and the Bad Plus took hold on the younger musicians who formed trios such as Phronesis and GoGo Penguin. Like the string quartet in classical music and the two-guitars–bass-and-drums group in rock and roll, its components are held together in perfect structural tension and offer limitless flexibility.

A few years ago, in response to a realisation that a phenomenon was under way, I reorganised my jazz CDs to provide a special alphabeticised section for piano trios. There were a lot of them, going back to Teddy Wilson, Art Tatum, Bud Powell, Thelonious Monk and Bill Evans and incorporating Herbie Nichols, Elmo Hope, René Urtreger, Mike Taylor, Martial Solal, Howard Riley, Bobo Stenson and many others, and the number grew fast as the influence of Keith Jarrett, Brad Mehldau, the Necks, EST and the Bad Plus took hold on the younger musicians who formed trios such as Phronesis and GoGo Penguin. Like the string quartet in classical music and the two-guitars–bass-and-drums group in rock and roll, its components are held together in perfect structural tension and offer limitless flexibility. Everyone has their own Sun Ra. Mine is the one who made the Heliocentric Worlds albums for the ESP label in the mid-’60s, and whom I saw a few times in the early ’70s — at the Berlin Philharmonie, the Festival Hall and the Village Gate. Jez Nelson, the host of the monthly Jazz in the Round series at the Cockpit Theatre, had barely heard of him before interviewing him for Jazz FM in 1990, but quickly embraced the whole Sun Ra trip and gave us some lovely stories at the tribute evening he organised on Monday, as did Gilles Peterson, who came along with a bag full of rare Ra vinyl to play in the bar during the interval.

Everyone has their own Sun Ra. Mine is the one who made the Heliocentric Worlds albums for the ESP label in the mid-’60s, and whom I saw a few times in the early ’70s — at the Berlin Philharmonie, the Festival Hall and the Village Gate. Jez Nelson, the host of the monthly Jazz in the Round series at the Cockpit Theatre, had barely heard of him before interviewing him for Jazz FM in 1990, but quickly embraced the whole Sun Ra trip and gave us some lovely stories at the tribute evening he organised on Monday, as did Gilles Peterson, who came along with a bag full of rare Ra vinyl to play in the bar during the interval. After Peterson’s DJ set came Where Pathways Meet, a nine-piece band comprising Axel Kaner-Lidstrom (trumpet), Joe Elliot (alto), James Mollison (tenor), Amané Suganami (keyboards and electronics), Maria Osuchowska (electric harp), Mark Mollison (guitar), Mutale Shashi (bass guitar), Jake Long (drums) and Kianja Harvey Elliot (voice). Named after a Sun Ra tune, and dedicated to making music animated by a reverence for his spirit, they went about their work with energy and enthusiasm. Any rawness in the execution seemed unimportant by comparison with the good feeling they imparted.

After Peterson’s DJ set came Where Pathways Meet, a nine-piece band comprising Axel Kaner-Lidstrom (trumpet), Joe Elliot (alto), James Mollison (tenor), Amané Suganami (keyboards and electronics), Maria Osuchowska (electric harp), Mark Mollison (guitar), Mutale Shashi (bass guitar), Jake Long (drums) and Kianja Harvey Elliot (voice). Named after a Sun Ra tune, and dedicated to making music animated by a reverence for his spirit, they went about their work with energy and enthusiasm. Any rawness in the execution seemed unimportant by comparison with the good feeling they imparted. For two hours on Friday night, Caetano Veloso invited us into his living room. Well, the Barbican Hall, actually, but that’s how he made it seem. His guests were the singer Teresa Cristina and the guitarist Carlinhos Sete Cordas, who began the evening by performing songs from their recent album, a collection of duets on pieces by the late samba composer Angenor de Oliveira, better known as Cartola (the album is titled Canta Cartola).

For two hours on Friday night, Caetano Veloso invited us into his living room. Well, the Barbican Hall, actually, but that’s how he made it seem. His guests were the singer Teresa Cristina and the guitarist Carlinhos Sete Cordas, who began the evening by performing songs from their recent album, a collection of duets on pieces by the late samba composer Angenor de Oliveira, better known as Cartola (the album is titled Canta Cartola). Record Store Day seems to have made a natural partnership with the vinyl revival, and one excellent way of marking tomorrow’s 10th anniversary of a very worthwhile institution would be to invest in the specially timed 12-inch 33 1/3rd rpm release of Smokin’ in Seattle, 50-odd minutes of newly discovered 1966 club recordings by the trio of the pianist Wynton Kelly, with Ron McClure on bass and Jimmy Cobb on drums, plus their special guest, the nonpareil guitarist Wes Montgomery.

Record Store Day seems to have made a natural partnership with the vinyl revival, and one excellent way of marking tomorrow’s 10th anniversary of a very worthwhile institution would be to invest in the specially timed 12-inch 33 1/3rd rpm release of Smokin’ in Seattle, 50-odd minutes of newly discovered 1966 club recordings by the trio of the pianist Wynton Kelly, with Ron McClure on bass and Jimmy Cobb on drums, plus their special guest, the nonpareil guitarist Wes Montgomery. A packed house celebrating the 70th birthday of the bassist and composer Barry Guy provided the best possible start to the Swiss record label Intakt’s 11-day festival at the Vortex on Sunday night. The opening evening showcased Guy in dialogues with three of his closest collaborators across a 50-year career: the violinist Maya Homburger, the saxophonist Evan Parker and the pianist Howard Riley.

A packed house celebrating the 70th birthday of the bassist and composer Barry Guy provided the best possible start to the Swiss record label Intakt’s 11-day festival at the Vortex on Sunday night. The opening evening showcased Guy in dialogues with three of his closest collaborators across a 50-year career: the violinist Maya Homburger, the saxophonist Evan Parker and the pianist Howard Riley. They’ve kept Studio 2 at Abbey Road looking much the way it did in 1967. The walls and movable screens are still covered with the sort of perforated acoustic pasteboard once found in record-shop listening booths. If you look up, you’ll see the window high in the wall through which George Martin looked down from the control room on “the boys”, as he always called them. Behind the cupboard doors you might even find random things to scrape or shake, as the need arises. There are scuffs and stains; like the interior of a vintage car, it has a patina.

They’ve kept Studio 2 at Abbey Road looking much the way it did in 1967. The walls and movable screens are still covered with the sort of perforated acoustic pasteboard once found in record-shop listening booths. If you look up, you’ll see the window high in the wall through which George Martin looked down from the control room on “the boys”, as he always called them. Behind the cupboard doors you might even find random things to scrape or shake, as the need arises. There are scuffs and stains; like the interior of a vintage car, it has a patina. Like the Jaynetts’ “Sally Go ‘Round the Roses”, the Dixie Cups’ “Iko Iko” and Shirley Ellis’s “The Name Game” and “The Clapping Song”, Rufus Thomas’s “Walking the Dog” was one of a bunch of early-’60s hits that made reference to playground songs. It was also a great R&B record, one of those that all British groups of the time had to learn.

Like the Jaynetts’ “Sally Go ‘Round the Roses”, the Dixie Cups’ “Iko Iko” and Shirley Ellis’s “The Name Game” and “The Clapping Song”, Rufus Thomas’s “Walking the Dog” was one of a bunch of early-’60s hits that made reference to playground songs. It was also a great R&B record, one of those that all British groups of the time had to learn.

The man who took the photograph that appeared on the cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan died on March 18, aged 88.

The man who took the photograph that appeared on the cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan died on March 18, aged 88.