1965: Annus mirabilis

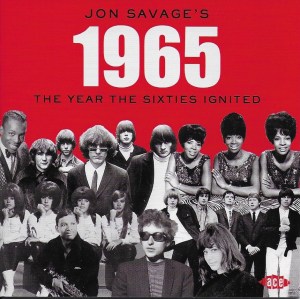

When Jon Savage compiled his excellent 2-CD sets of hits and curiosities from 1966 and 1967 for Ace Records, he was just clearing his throat. Now, with 1965: The Year the Sixties Ignited, he arrives at the real point of the exercise: a celebration of the best year in the history of popular music. OK, I’m biased: I was 18, which is a pretty important age to be. Jon’s selection of 48 tracks on two discs is characteristically idiosyncratic and stimulating; mine would be very different. I loved 1965 while it was happening, and I’ve felt that way ever since. Twenty years ago I wrote a piece about it for the Independent on Sunday’s Review section, and then expanded it slightly for inclusion in a collection of my music pieces titled Long Distance Call. Here, because you almost certainly won’t have read it in either form, is a truncated version.

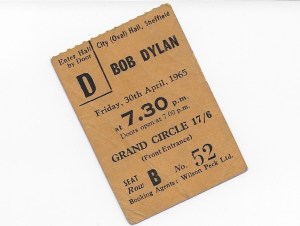

IT’S A FRIDAY evening in the spring of 1965. In a house in the Midlands, an 18-year-old boy is waiting to take a 17-year-girl to the opening night of Bob Dylan’s first British concert tour. He has two tickets in his pocket. Sheffield City Hall, grand circle, second row, seven shillings and sixpence each.

The television is on as they prepare to leave her parents’ house. It’s Ready Steady Go!, live from London, the weekly hotline to the heart of whatever’s hip. One of the presenters — either the dollybird Cathy McGowan or the incongruously avuncular Keith Fordyce — announces the appearance of a new group. They’re from America, they’re called the Walker Brothers, and this is their first time on British TV. Their song is called “Love Her”.

On the small black and white screen, the face of a fallen angel appears. The boy and the girl are already cutting things fine for Dylan, but still the girl freezes in the act of putting on her coat and, as if in slow motion, sits down to watch the 21-year-old Scott Engel, clutching the microphone as though it were a crucifix, delivering the straining, heavily orchestrated teen ballad in a dark brown voice borrowed from the romantic hero of a comic strip in Romeo or Valentine.

As the song ends and the image fades, the girl shakes herself lightly, refocuses on her surroundings and pulls on her coat. OK, she says. Ready to go.

A COUPLE OF hours later they would be among the first people in Britain to feel the impact of the new songs that were still a fortnight away from release on Dylan’s fifth album, Bringing It All Back Home. With “It’s Alright Ma”, “Gates of Eden”, “Love Minus Zero”, “Mr Tambourine Man” and “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”, a flood of dazzling images and ideas was released. “The lamp post stands with folded arms, its iron claws attached…” “He not busy being born is busy dying…” “To dance beneath the diamond sky / With one hand waving free… ” He was bringing the unformed thoughts of his audience into focus, inventing new emotions and redefining old ones.

Reeling out into the night, speechless with awe, saturated by those visions, they couldn’t know that Dylan was already bored with the way he’d been presenting himself up. The Beatles, Rolling Stones and Animals may have worshipped him, but he wanted what they’d got. Less than two months after opening that tour in Sheffield, he would convene a full-tilt rock and roll band in a New York studio to record “Like a Rolling Stone”, the first six-minute 45. In July he took a band with him on to the stage at the Newport Folk Festival, where he had been a hero in previous years but was now reviled for his supposed act of heresy. Highway 61 Revisited and “Positively 4th Street” followed, in all their ornate mystery.

But although his change of direction was a shock, it was not a surprise. Because in 1965 change was expected: every month, every week, almost every day. Every time you walked into a record shop, opened a book, bought a magazine, turned on the TV. Between picking up your coat and putting it on.

THE YEAR 1965 started with the Righteous Brothers’ “You’ve Lost that Lovin’ Feelin'” (the greatest of all orchestral pop records) and ended with the Beatles’ Rubber Soul (their most satisfying album) and contained so much great music that it would take a year to listen to it, even now. In the sense that pop musicians were still waking up to the reality of their own economic power, and had not yet taken the logical step of attempting to control the means of production, this was also the last year of innocence.

It was filled with perfect examples of what we think of as ’60s moments. David Bailey wore a crewneck sweater to marry Catherine Deneuve. Mods and rockers spent the Easter holiday hurling deckchairs at each other on the Brighton seafront. Marianne Faithfull, much to her own surprise, turned down Bob Dylan’s advances (she was pregnant and about to marry a man who owned a bookshop and art gallery). Julie Christie starred in John Schlesinger’s Darling and Jane Birkin flitted in and out of Richard Lester’s The Knack, giving us two defining images of Swinging London. The Beatles reunited with Lester to make Help!, played Shea Stadium, visited Elvis at home in Beverly Hills, and went to Buckingham Palace to receive their MBEs and smoke dope in the lavatories — not quite all on the same day, but almost. Liverpool, probably not coincidentally, won the FA Cup for the first time. Jean Shrimpton (whose sister was going out with Mick Jagger) lived with Terence Stamp (whose brother was managing the Who) and horrified Australian society by turning up to the Melbourne Cup in a simple shift dress that terminated four inches above her knees.

That’s how easy it was to shock people in those days. When a small rip opened up in the weakened crotch seam of the American singer P. J. Proby’s velvet trousers on stage in Croydon in January, he was banned by the ABC theatre chain and excoriated by the newspapers. When three of the Stones — Jagger, Richards and Wyman — were reported to have urinated against a wall at a petrol station on the way home from a show in Romford, they made the front pages and were fined £5 each. There was a fuss about these incidents but under the outrage, much of it bogus, there was a sense that they were adding to the gaiety of the nation.

In what was left of the real world of Great Britain, the Kray twins were being remanded, the Moors Murderers were charged, Harold Wilson’s government announced an “experimental” 70mph speed limit, legal blood-alcohol limits for drivers were brought in, and incitement to racial hatred was banned. Heath succeeded Home as Tory leader and declared his intention to take Britain into the Common Market — to which, in any case, the government had just applied for a £500 million loan. Internationally, the big issues were the Vietnam war and civil rights, both of which spilled over the frontiers of the United States and commanded the attention and concern of young people throughout the world.

In January, Lyndon Johnson sent the B-52s to bomb North Vietnam. In June, the first American troops went into action on the ground against Vietcong bases near Saigon; by the time they got there, the VC had vanished. The President’s answer: send more troops. the Rev Dr Martin Luther King was arrested during a voter-registration protest in Selma, Alabama; eight weeks later he marched back into town at the head of 25,000 people, protected by 3,000 federal troops and the camera crews of the world’s television networks. Between times, Malcolm X had met an assassin’s bullet in New York. In August, 28 people died and 676 were injured when Watts exploded in three days of rioting.

Everything seemed connected, somehow or other. When Cassius Clay beat Sonny Liston to take the heavyweight championship of the world, even that was part of the bigger deal: the youthquake, black power, the generalised feeling that the Establishment was there for the taking. Liston and Floyd Patterson, against whom Clay subsequently defended his title, were black, too, but other, older kinds of black. Clay was Dylan’s age, Jagger’s age, Lennon’s age. Our age.

And ours was also a visual age. Coming between the studied sloppiness of the Beat generation — sandals and shapeless sweaters — and the romantic self-indulgence of the hippies, it was the time of the mods, whose aesthetic may have ended up with the skinheads of the British Movement but had begun with better intentions in the jazz clubs of Soho, the tailors of Whitechapel and the liberal atmosphere of the London art colleges, among people who knew about Fellini and Jasper Johns.

Much of that came together in the Who, who began the year with the terse, staccato chords of their first single, “I Can’t Explain”. They ended it with the thrillingly anarchic feedback of “My Generation”. In between came “Anyway Anyhow Anywhere”, described by Pete Townshend, its composer, as “anti-middle age, anti-boss class, and anti-young marrieds”. If the Who had packed it all in at Christmas, after those three 45s, they’d have been regarded as the greatest rock group of all time, no contest.

British rock music, high on its own huge success in the US and fuelled by a profound admiration of Bob Dylan’s wilful unpredictability, was moving away from covers of Chess and Motown records and beginning to explore its creative potential. The Beatles started to enter the regions beyond two-dimensional love songs, distilling the darker complexities of “Help!” and “Norwegian Wood”, both indelibly marked by Dylan’s influence on Lennon, while George Martin’s experience enabled Paul McCartney to achieve the imaginative leap that led to “Yesterday”.

The Stones, with Jagger and Richards forced into the role of composers by their manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, who recognised the value of copyrights, used the influence of Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters to create the template for riff-based rock music with “The Last Time” and “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”, benefitting from Keith’s acquisition of something called a fuzz box and from the funkier ambiance of American studios. The Animals built a denser sound, more conscious of dynamics, with “We’ve Gotta Get Out of This Place” and “It’s My Life”. The Yardbirds were experimenting with mood and structure on “For Your Love” and the quasi-liturgical “Still I’m Sad”. Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames emerged from the Flamingo all-nighters with the finger-popping “Yeh Yeh”, the sound of an Ivy League jacket and a French crop. The Kinks progressed from the kinetic power chords of “Tired of Waiting for You” to the prophetic quasi-oriental drone of “See My Friends”, which anticipated raga-rock and a certain strand of psychedelia. The Small Faces (real, rather than art-school, mods) made their debut with the pugnacious “Whatcha Gonna Do About It?”, a healthy plundering of the chord-riff from Solomon Burke’s “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love”. Out of Belfast came the incomparably surly Them with “Baby Please Don’t Go”, a devastatingly supercharged version of a country-blues text, followed by “Here Comes the Night” and the opening chapter of the Van Morrison legend.

“Gloria”, the B-side of “Baby Please Don’t Go”, may have been the first punk-rock record. Or perhaps that was the pounding “I Want Candy” by the Strangeloves, a non-existent group created to counter the British invasion by a bunch of New York studio-hack writer-producers. Or possibly it was the magnificently silly “Wooly Bully” by Sam the Sham and the Pharoahs, or the Sir Douglas Quintet’s “She’s About a Mover”, out of Texas. Or, from New York once more, the McCoys’ “Hang on Sloopy”, a kind of punk-bubblegum hybrid based on the Vibrations’ vastly superior “My Girl Sloopy”. The year was full of one-offs like these as American groups (and the commercial interests behind them) fought back, producing guitar-driven music to counter that coming from the other side of the ocean.

The Byrds — not a one-off — took an electric 12-string guitar to his “Mr Tambourine Man” and invented jangling folk-rock (refined later in the year with “Turn Turn Turn”, their version of Pete Seeger’s take on the Book of Ecclesiastes). Music producer Lou Adler bought his staff songwriter Phil Sloan a corduroy Dylan cap, handed him a copy of Highway 61 Revisited and an acoustic guitar, and locked him in a Hollywood bungalow for a weekend. On the Monday morning Sloan handed Adler the demo tape of “Eve of Destruction”, an instant worldwide No 1 for the hoarse-voiced Barry McGuire.

Harold Battiste, a veteran of the New Orleans R&B scene, helped a couple of Hollywood brats, Salvatore Bono and Cherilyn LaPier, to become Sonny and Cher with “I Got You Babe”, a folk-rock minuet with an oboe where most records would have a guitar or a saxophone. Brian Wilson, fiddling about in his studio while the rest of the Beach Boys toured the world, pushed the enrichment button on surf music so hard that it turned into the sunlit symphonies of “Help Me Rhonda” and “California Girls”. The Everly Brothers, relics of pop’s first golden age, a duo with roots in the music of the Appalachian chain, were reborn with the crunching drive of “Love Is Strange”, as powerful a sound as any in the whole year,

In cities around America, soul music had reached its mature phase. Detroit’s Hitsville USA was in top gear with Marvin Gaye’s “Ain’t That Peculiar”, Martha and the Vandellas’ “Nowhere to Run”, Kim Weston’s “Take Me in Your Arms”, Jr Walker’s “Shotgun”, the Marvelettes’ “I’ll Keep Holding On”, Stevie Wonder’s “Uptight”, the Four Tops’ “I Can’t Help Myself” and “It’s the Same Old Song”, the Supremes’ “Stop! In the Name of Love” and “Back in My Arms Again”, and half a dozen Smokey Robinson masterpieces: three for the Temptations (“My Girl”, “It’s Growing” and “Since I Lost My Baby”) and three for his own group, the Miracles (“Ooo Baby Baby”, “Goin’ to A Go-Go” and the incomparable “Tracks of My Tears”). In Chicago, Curtis Mayfield was using the memory of his grandmother’s Sunday morning church sermons to create “People Get Ready”. In Memphis, the Stax house band was launching Wilson Pickett into “In the Midnight Hour” and Otis Redding into “Respect”. James Brown stopped off while touring to record “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” in Charlotte, North Carolina and “I Got You (I Feel Good)” in Miami, Florida.

That’s to say nothing of Barbara Mason’s swooning “Yes I’m Ready”, the Dixie Cups’ “Iko Iko” and Shirley Ellis’s “The Clapping Song” (which both found new uses for children’s playground songs), Lou Christie’s falsetto tour de force on “Lightning Strikes”, Betty Everett’s “Getting Mighty Crowded”, Tom Jones’s “It’s Not Unusual”, the Shangri-Las’ “I Can Never Go Home Any More”, the Ronettes’ “Born to Be Together” (their finest moment), the Drifters’ “At the Club”, Dusty Springfield’s glowing “Some of Your Loving”, Petula Clark’s “Downtown”, and the boiling, gospel-driven “Heartbeat Pts 1 and 2” by Gloria Jones. Or Dionne Warwick’s staggering “(Here I Go Again) Looking With My Eyes (Seeing With My Heart)”, the Searchers’ “What Have They Done to the Rain”, Wayne Fontana’s “Game of Love”, Fontella Bass’s “Rescue Me”, the Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Do You Believe in Magic?”, Dobie Gray’s “The ‘In’ Crowd”, Little Richard’s utterly magnificent “I Don’t Know What You Go But It’s Got Me Pts 1 and 2”, and, to get back to where we started, two further Walker Brothers classics, “Make It Easy on Yourself” and “My Ship Is Coming In”. All of them — and many others — still played and recognised today.

MOST SIGNIFICANTLY, though, and paradoxically in the light of all this frantic activity, 1965 was the year in which pop music started to slow down. First there was the way in which the working process itself became more leisurely, a result of increasing affluence among musicians who had started out two or three years earlier traipsing up and down the M1 crammed into Transit vans, and the freedom it gave those who had previously been the slaves of managers and record companies. And there was the accompanying desire to spend more time creating records in the studio, exploring the potential of both the developing technology and the musicians’ own imaginations.

In 1965 the Beatles, as they had every year since signing with EMI, released two albums, Help! and Rubber Soul. The Stones released No. 2 and Out of Our Heads. The Beach Boys released Today and Summer Days (and Summer Nights!). That was the standard working schedule. But in 1965 the sense of artistic competitiveness was growing fast. The Beatles would hear the new Beach Boys single and know they had to top it. The only way was to spend more time in the laboratory. The following year, there would be only one album from each of these three leading bands: Revolver, Aftermath and Pet Sounds. And that would remain the pattern.

The music also slowed down in a more literal and far-reaching sense, thanks to the combined influence of James Brown and Andy Warhol. Together, the effect of Brown’s one-chord funk in the clubs and the influence of Warhol’s image-repetition in the art colleges began to thin out the music’s layers, simplifying its structure and reducing the density of its content. This was the birth of pop minimalism, and it also led directly to the inversion of what might be called the music’s weight distribution. Where the aural focus had been on the lead voice(s) — an emphasis reflecting the old “Vocal with rhythm accompaniment” tag that used to be printed on the labels of pre-war 78s, under the singer’s name — now the bottom end of the rhythm section began to take greater prominence. This shift of balance arrived hand in hand with technological developments allowing discothèques to install sound systems which played extra emphasis on the elements of the music that made people dance: the bass and drums. In that sense the most important records of 1965 were not “Satisfaction”, “Ticket to Ride” or “My Generation”, but “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” and “I Got You (I Feel Good)”, whose long-term effect on the time-frame and event-horizon of popular music is all around us today — in disco and house music, hip-hop, drum ‘n’ bass, trance, and just about everything else.

Buried within 1965, then, were the seeds of 1966, which also included the debut of Jefferson Airplane at the Matrix in San Francisco and of the Grateful Dead at the first Acid Tests. In November, the two bands shared the bill at the opening night of Bill Graham’s Fillmore Auditorium. That same month, on the east coast, Lou Reed and John Cale gave their new band a name under which they played their first gigs in a New Jersey high school auditorium. Around the corner of the new year lay Cream, Pet Sounds, “Paint It Black”, “Eleanor Rigby”, the aloof visions of Blonde on Blonde and the tumultuous tour that prefaced Dylan’s motorcycle crash. And The Velvet Underground and Nico, with which another future would begin.

Free improvisation is a complex business. Is the idea to create something from nothing that nevertheless sounds as though it was pre-composed? Surely not, although that can be an occasional effect. The reissue of Karyōbin, the SME’s second album, taped in February 1968, shows the music in an embryonic state, when individuals were still mixing and matching their discoveries and feeling their way towards a true group music.

Free improvisation is a complex business. Is the idea to create something from nothing that nevertheless sounds as though it was pre-composed? Surely not, although that can be an occasional effect. The reissue of Karyōbin, the SME’s second album, taped in February 1968, shows the music in an embryonic state, when individuals were still mixing and matching their discoveries and feeling their way towards a true group music. One of the nicer things that happened to me in 2017 was an encounter with Corinne Drewery and Andy Connell, otherwise known as Swing Out Sister. The circumstances — the funeral in Grimsby of Corinne’s dad, the lead singer and bass guitarist with the R&B band in which I played during the mid-’60s — could have been happier. But it was fun to tell her about the band, about the nights we supported Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and Tom Jones, and about how Rae, her dad, was always on at me — quite correctly — to stick to a simple backbeat rather than trying to lay Elvin Jones licks all over the 12-bar blues of Jimmy Reed and Howlin’ Wolf.

One of the nicer things that happened to me in 2017 was an encounter with Corinne Drewery and Andy Connell, otherwise known as Swing Out Sister. The circumstances — the funeral in Grimsby of Corinne’s dad, the lead singer and bass guitarist with the R&B band in which I played during the mid-’60s — could have been happier. But it was fun to tell her about the band, about the nights we supported Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and Tom Jones, and about how Rae, her dad, was always on at me — quite correctly — to stick to a simple backbeat rather than trying to lay Elvin Jones licks all over the 12-bar blues of Jimmy Reed and Howlin’ Wolf.

As soon as she made her first record with her family’s gospel-singing group in the early 1950s, Mavis Staples made it clear that she occupied a vocal and emotional register of her very own. At the age of 14, already she could invest the lines “Won’t be the water / But the fire next time” with an almighty dread. Today, at 78, she may have lost some of the range and raw power of her youth but she retains every ounce of the visceral impact. And in terms of its relevance to the state of the world, her new album, If All I Was Was Black, takes its place among the year’s most essential recordings.

As soon as she made her first record with her family’s gospel-singing group in the early 1950s, Mavis Staples made it clear that she occupied a vocal and emotional register of her very own. At the age of 14, already she could invest the lines “Won’t be the water / But the fire next time” with an almighty dread. Today, at 78, she may have lost some of the range and raw power of her youth but she retains every ounce of the visceral impact. And in terms of its relevance to the state of the world, her new album, If All I Was Was Black, takes its place among the year’s most essential recordings. Otis Redding died 50 years ago today, on December 10, 1967, when his light plane crashed into a lake near Madison, Wisconsin. Six others — the pilot, Otis’s valet, and four members of his band, the Bar-Kays — also lost their lives. A fifth musician, the trumpeter Ben Cauley, was the only survivor.

Otis Redding died 50 years ago today, on December 10, 1967, when his light plane crashed into a lake near Madison, Wisconsin. Six others — the pilot, Otis’s valet, and four members of his band, the Bar-Kays — also lost their lives. A fifth musician, the trumpeter Ben Cauley, was the only survivor. On this side of the English Channel, we spent decades laughing at Johnny Hallyday. He was the eternal proof that the French couldn’t do rock ‘n’ roll. At all. But if there was one quality that defined Johnny, apart from his obsession with American popular culture, it was persistence. And eventually I saw past the dreadful cover versions of US hits (“Viens danser le Twist”) and found myself starting to enjoy and even admire what he did.

On this side of the English Channel, we spent decades laughing at Johnny Hallyday. He was the eternal proof that the French couldn’t do rock ‘n’ roll. At all. But if there was one quality that defined Johnny, apart from his obsession with American popular culture, it was persistence. And eventually I saw past the dreadful cover versions of US hits (“Viens danser le Twist”) and found myself starting to enjoy and even admire what he did. This is the line of ticket-holders waiting to enter Cafe Oto for the Necks’ sold-out lunchtime concert today. It might have seemed an unusual time of day to experience the intensity of free collective improvisation, but the Australian trio’s music tends to work its unique magic at any time of day or night, in any location.

This is the line of ticket-holders waiting to enter Cafe Oto for the Necks’ sold-out lunchtime concert today. It might have seemed an unusual time of day to experience the intensity of free collective improvisation, but the Australian trio’s music tends to work its unique magic at any time of day or night, in any location. Abrahams began the first set with tentative piano figures, joined by Buck’s bass drum and, eventually, Swanton’s arco bass. The pianist tended to hold the initiative throughout, creating arpeggiated variations that slowly surged and receded, gradually building, with the aid of Buck’s thump and rattle and the keening of Swanton’s bow, to a roaring climax — including, from unspecified source among the three, a set of overtones that gave the illusion of the presence of a fourth musician — before tapering down to a perfectly poised landing.

Abrahams began the first set with tentative piano figures, joined by Buck’s bass drum and, eventually, Swanton’s arco bass. The pianist tended to hold the initiative throughout, creating arpeggiated variations that slowly surged and receded, gradually building, with the aid of Buck’s thump and rattle and the keening of Swanton’s bow, to a roaring climax — including, from unspecified source among the three, a set of overtones that gave the illusion of the presence of a fourth musician — before tapering down to a perfectly poised landing.