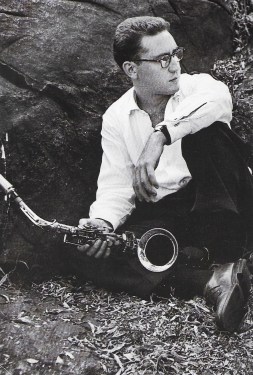

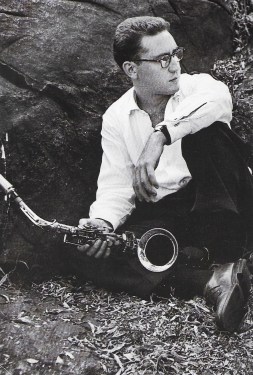

One of the things we value most about jazz is the way it encourages — even relies on — the expression of individual character. A musician’s “sound” (a combination of factors, including tone, phrasing, attack and harmonic sense) is as personal as a fingerprint. Learning to differentiate between them is one of the tests and pleasures of being a young fan. Lee Konitz, who has died at the age of 92 from the effects of the coronavirus, had a more identifiable sound than most right from the start, but what was different about him was that he never allowed it to harden into a series of familiar gestures. Instead he showed a willingness to allow his style to evolve naturally as time passed.

There was a good example one night in 1992, when Gerry Mulligan arrived in London with a version of what is thought of as the Miles Davis Birth of the Cool nonet, containing several original members (with Lew Soloff playing Miles’s role). Konitz had joined up for their European tour, and at the Queen Elizabeth Hall it was noticeable that the altoist was the only one who, when his solos came round, did not in any way attempt to reproduce his work on the original recordings 40-odd years earlier. His timbre had thickened and his lines no longer flew with the blithe adroitness of someone who could play whatever lay under his fingers, but there was a deeper kind of thought in every weighted phrase.

He was the most open of musicians: a career that began with Claude Thornhill and Lennie Tristano ended in collaborations with Brad Mehldau and Ethan Iverson. En route he played with an astonishing cornucopia of musicians, from Warne Marsh and Chet Baker through Jimmy Giuffre, Charles Mingus, Bill Evans, Elvin Jones, Henry Grimes, Paul Motian, Charlie Haden, Gary Peacock, Bill Frisell and countless others. He played with Charlie Parker, on tour with Stan Kenton in 1953, and with Ornette Coleman at the 1998 Umbria Jazz Festival. He was great in a formal setting, playing Gil Evans’s charts with Thornhill’s big band or Miles’s nine-piece, and he could be even better with an unfamiliar pick-up rhythm section, using the most mundane of formats to explore the extensions of melody and harmony.

During an earlier visit to London, in June 1983, on an otherwise perfectly ordinary night in a perfectly ordinary jazz club, in front of a perfectly ordinary audience, he produced one of the most extraordinary jazz performances I’ve ever heard. Here’s what I wrote about it a few years later, in the introduction to Jazz Portraits, a book of photographs:

On this night, a few evenings into a fortnight’s season that was part of a typical American jazz musician’s summer spent moving between the clubs and festivals of Europe, Konitz was working with three British players: Bob Cornford, a classically trained composer and pianist; Paul Morgan, a young double bassist; and Trevor Tompkins, a highly experienced drummer. Within a month of this engagement, the quiet, unemphatic Cornford, who revered Béla Bartók and Bill Evans in equal measure, would be dead of a heart attack at the age of 43, his immense promise unfulfilled, his gifts revealed only to a handful of his peers.

Konitz, like all of Tristano’s pupils, was known for his reliance on the chord sequences of standard Broadway ballads. They had been good enough for Lester Young and Charlie Parker, Tristano’s twin avatars of improvisation, and they were good enough for Lee Konitz. But this set on this particular night began with what seemed like a free improvisation: brief snatches of elliptical melody, angular and discontinuous, connected to each other only by the most tenuous logic. Or so it seemed. But gradually, with Cornford, Morgan and Tompkins following every step, the saxophonist’s phrases began to form more explicit links, even starting to describe familiar shapes. Slowly, as if from a pale mist, a tune emerged.

The process described in that paragraph may have taken five minutes, or it may have taken fifteen. No one was keeping score, and one of the special properties of improvisation — and not just jazz improvisation — is that it can take hold of chronological time and distort it: speeding it up, slowing it down, bending it, stopping it altogether. Now Konitz briefly ruled time, making it obey his commands as he lingered over the revealed contours of his design, sprinting forwards and pulling back until he judged the moment right to unveil the unmistakable shape of a standard.

Imagine a three-dimensional jigsaw, made out of glass, assembling itself in mid-air. Such was the quiet strength of Konitz’s creative conviction that his partners in the rhythm section never felt the lack of specific directions or signposts. When the tune of “On Green Dolphin Street” finally emerged as a more or less complete entity, it was the product of an organic process. Unlike most improvisers of his generation, who take the material and reassemble it into something of their own, Konitz had reversed the process.

A dozen years later, it was impossible to recall specific phrases from a piece of music that disappeared into the air as soon as it had been played. But the sound and the shape of the music, and the quality of absolute uniqueness that they gave to this apparently mundane event, were etched indelibly upon the memory.

Today I’ll listen to Konitz on Gil Evans’s recasting of “Yardbird Suite” for Claude Thornhill in 1947, to his participation in Lennie Tristano’s “Intuition”, the first attempt at pure collective improvisation in modern jazz in 1949, to his sound colouring the texture of the Davis/Evans version of “Moon Dreams” in 1950, to this “All the Things You Are” with the Gerry Mulligan Quartet at the Haig Club in LA in 1953, to this “All of You” with Sonny Dallas on bass and Elvin Jones on drums from 1961, and this “Alone Together” with Brad Mehldau and Charlie Haden from a great Blue Note trio album of the same name, recorded in 1996.

* The photograph of Lee Konitz was taken by William Claxton and appeared in Jazz Portraits (Studio, 1994). Andy Hamilton’s book Lee Konitz: Conversations on the Improviser’s Art (University of Michigan Press, 2007) is highly recommended.