Harmolodics: the truth at last

So I’m wandering into Mayfair on Monday, on my way to the launch party for this year’s EFG London Jazz Festival, and I have 10 minutes to spare. On Dover Street there’s an antiquarian book shop called Peter Harrington. I’ve never been in there before but there’s some nice stuff in the window so I open the door.

So I’m wandering into Mayfair on Monday, on my way to the launch party for this year’s EFG London Jazz Festival, and I have 10 minutes to spare. On Dover Street there’s an antiquarian book shop called Peter Harrington. I’ve never been in there before but there’s some nice stuff in the window so I open the door.

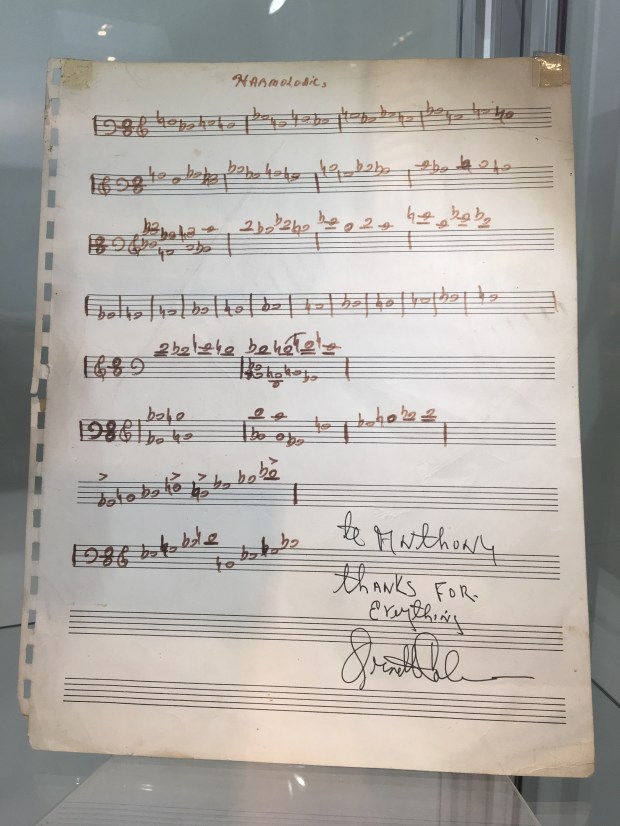

Within a couple of minutes I’ve forgotten all about the stuff in the window. There are clues to what’s about to happen in a shelf of jazz-related publications, including Johnny Otis’s Listen to the Lambs, a signed copy of Dizzy Gillespie’s To Be or Not to Bop. and a complete set of Les Cahiers du Jazz, 1959-64. But then I see a display case. Inside it — alongside a signed photograph of Sonny Rollins mowing a lawn in Sweden, taken by the famous jazz critic Randi Hultin, rather incongruously juxtaposed with an autographed and dedicated copy of Marc Bolan’s volume of poetry, The Warlock of Love — is a sheet of manuscript paper. The word scrawled at the top is “Harmolodics”. The signature at the bottom is that of Ornette Coleman.

Harmolodics was Ornette’s system of musical organisation — one apparently based on a highly personal disregard of regular methods of transposition for wind instruments. You knew it when you heard it: it was what made his music sound the way it did. But whenever interviewers asked him to explain it — and I was among their number myself — the answer was so gnomic and cryptic as to be beyond normal comprehension. Which was certainly not to say that there was anything wrong with it.

Anyway, this piece of manuscript paper headed “Harmolodics” contains eight staves of musical annotation and looked as if it might explain something. Seeking enlightenment, I sent my snapshot of it to the pianist Alexander Hawkins, who shot back a reply within an hour. It turned out that, by coincidence, he had just been transcribing some chords from Prime Design/Time Design, Ornette’s piece for string quartet and drums, dedicated to Buckminster Fuller and recorded in 1985 at the Caravan of Dreams festival in Fort Worth. Interestingly, he was immediately struck by certain similarities. Here’s an extract from his reply:

On the third line up from the bottom on the Ornette manuscript, that Eb-Gb minor 10th/compound minor third interval… is embedded in the string quartet harmony. Ornette’s chromatic scale (4th stave down) yields this harmony when it is read with different clefs. So that first pitch (the flattened note on the bottom line of the staff) of course reads as the Eb in the treble clef, and as a Gb in the bass clef. If you then invert that interval of the minor third, you get a major sixth; and sure enough, a major sixth is the voicing between the ‘cello and viola in the quartet… This system of ‘equivalences’ you can also see in Ornette’s bottom two staves. The arpeggio which he spells out – bottom line, first four notes – reads Eb – G – Bb – D in the bass clef, or Cb (=B) – E – Gb – B in the treble clef. Hence, perhaps, the next four notes on that bottom line, which in the bass clef read of course B – Eb – Gb – Bb. (Although I can’t at present explain with this isn’t B – E natural – Gb – B natural: it seems unlikely that Ornette would slip up on two accidentals)…

I was told by the bookseller that the manuscript was the property of the dedicatee, a man who had helped Ornette with archiving his papers and had been given it as a present. It may have been lying around on Ornette’s floor; there’s what seems to be the faint trace of a footprint, possibly from a trainer, on the right-hand side.

In case you’re thinking that it might be a nice thing to have hanging on the wall, here’s the sticker price:

£10,000.

Wow – that’s magical.

Fascinating story! – hard to comment without seeing the chart but perhaps the convention that a part written in the bass clef concert key can be read by Eb instruments and sound correct ( Ornette being an alto player) just by imaginarily changing the clef …has something to do with it… ?

My comment above made purely on reading Alex Hawkin’s description… without seeing the photo until now: indeed with different bass and treble clefs written on the same stave. This could indicate a key element of his musical method – ie introduce a free choice ( each player picks his own note and clef) to improvise off introducing harmonic unpredictability but some unity or coherence in following the pattern of intervals up or down.

Those have played with him could surely give the definitive answer if they saw this!

Hi Adam – on the choice of clef thing – a really interesting analogy here is Braxton’s ‘diamond clef’, which behaves very similarly to the situation you describe. (Hope you’re really by the way – catch you soon I hope.)

Is the Anthony Braxton?

No, Geoff. It’s a man called Anthony Murrell.

Not in any way alienating for us non-musicians. Just like Dominic Lash’s thesis on (partly) Derek Bailey. Seek it out and scratch your head.

Good grief, what a price tag!

Very interesting though, Richard, a wonderful find.

This is amazing! Thanks

I believe this is indeed authentic, as there are lots of pieces of paper like this floating around NYC: I have one myself. You could get one by visiting Ornette and he would gladly write in your music notebook. The script can also be seen “published” in the liner notes to SOAPSUDS, SOAPSUDS and a few other places.

However page is unusually clean and fine in presentation!

I have many opinions about Harmolodics. Don’t know if I’m right but I wrote them up here:

From that essay:

“According to Ornette, every instrument has its own pitches. You can get a special kind of sound if you train yourself, as he did in his early days, to think your notes are not just your concert or transposed notes but also true to the written (untransposed) page.

“He also believed that a line of music written on the page (or taught by rote) should mean something different to every musician. When Ornette realized that the same note on a music staff meant different notes on different instruments, he found a way to give everybody the same basic melody but have every musician be heard with their own emotion.”

The above score shows some of this in action, as the notes are written for three clefs. However, the accidentals don’t change, a wildly improbable situation for conventional notation. As I also say in the essay:

“The most thorough documentation of the transposition logic is Skies of America, where a whole orchestra reads off of one line for the complete record. (Very occasional counterpoint is generated somehow, probably not by Ornette.) It is sort of ridiculous to have all those London Symphony players doing this, of course. They regarded it as undignified.

“(In general, Ornette’s transposition logic makes experienced musicians scream in exasperation.)

“But then again, I have heard hours and hours of orchestral music in my life, and most of it hasn’t stayed with me. Skies of America—that scorched-earth, post-apocalyptic mayhem—I’ll never forget that sound.”

This is also the sound of Prime Design/Time Design. Kudos to Alexander Hawkins for transcribing it!

Ethan – I wish I could say I’d taken it all down (now there’s a project…)…was more transcribing voicings here and there, and thinking about how the system could generate them from an otherwise ostensibly unison line! [On the subject of transcription: as one Hampton Hawes nut to another, thank you for sharing those ones!]

Ethan: The drummer on the original recording of The Skies of America was Tristan Fry, the orchestra’s tympanist. (He’s the answer to the popular question: who played with Ornette Coleman at Abbey Road and at the wedding of Prince William at Westminster Abbey 39 years later?) There’s a brief description of the recording session in London here: https://thebluemoment.com/?s=Ornette+Coleman+Skies+of+America You might know that John Giordano, the conductor of the Fort Worth SO, had a go at reorchestrating it in the early ’90s; I heard that version in London — and while it might have done the orchestra players some favours, it did none for the piece itself.