Antony Price 1945-2025

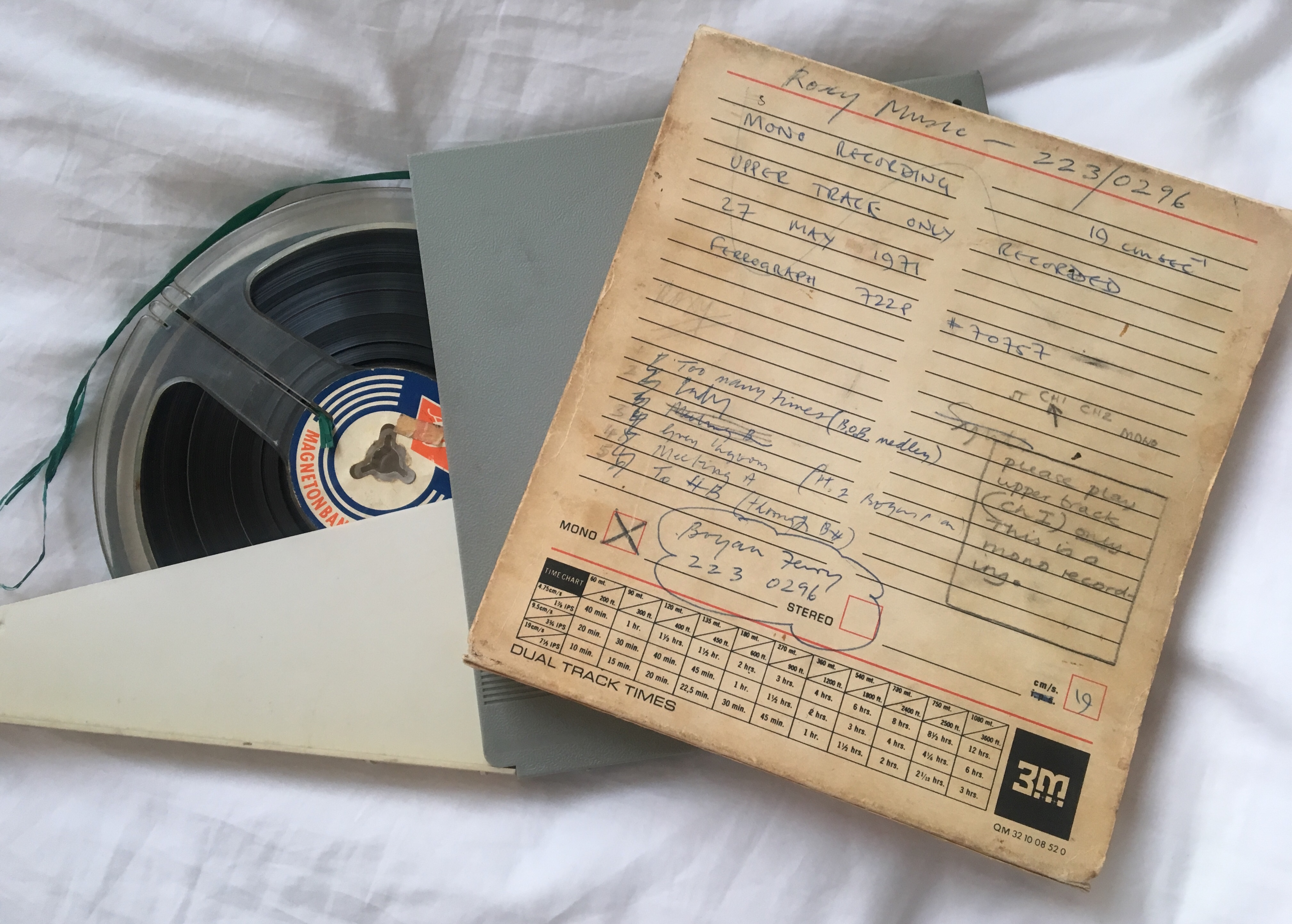

Of course there was the shock of the music, exquisite to some and befuddling to others. But it was the list of credit on the cover of the first Roxy Music album that really got people going. Concept by Bryan Ferry. Art by Nicholas de Ville. Photography by Karl Stoecker. Clothes, make-up and hair by Antony Price. Something different was going on here.

A lot of it had to do with Antony Price, a Yorkshire-born former Royal College of Art student who got together with Bryan Ferry to devise the group’s look. Price died this week, aged 80, having made a significant contribution to the way the culture around the music evolved in the 1970s. Price made the ruffled satin swimsuit in which Kari-Ann Moller posed on the wraparound gatefold cover image of that debut album, the strapless sheath dress that Amanda Lear wore on the front of For Your Pleasure, and so on all the way through Roxy’s eight studio albums.

Here’s Phil Manzanera, talking to me a few years ago about joining the band in 1972. “I remember getting on the 137 bus from Clapham to go to the photo session for the first album and of course I had no idea about style. My mum sewed some diamante on to a white shirt and I turned up at the session and Antony takes one look at me and says, ‘No, no, no!’ He hands me the bug-eye glasses. ‘Stick these on! And here’s a leather jacket!’ Job done. Fantastic. Antony was a bloody genius.”

Here’s how Ferry remembered putting that first cover together: “I think it was after the recording. Either we were still making, it, or just about finished. I remember calling Antony from a red phone box, I think in the King’s Road, which makes sense because I used to hang around EG (Management)’s offices. I was living in Battersea with Andy Mackay. I remember Antony saying, in his gruff way, ‘I want to hear what it sounds like!’ So I guess I went round to see him.

“Antony had this photographer friend who he’d already done a couple of things with, called Karl Stoecker, married to Errol Flynn’s daughter – a very handsome man, a real ladies’ man. We went to his studio and did this picture. Antony and I talked about it… (he) had this girl called Kari-Ann who he thought was ideal – I wanted a woman, dressed by him. It turned out to be the perfect thing to go with the music.”

What was the cover image saying? “All the ’50s references in the music, late ’50s, early ’60s, were being reflected. It wasn’t that long gone, but it seemed like an age. But although it was a cheesecake kind of thing, it was a bit more knowing. It was all in the details, I think… the make-up, everything, the gold disc – that was a conceit, a cheeky little thing. Yes, it was challenging – and she was looking in a challenging way. It was in the (pre-digital) days when you didn’t know if you had the picture at all. A week later you’d look at the prints. I was so excited.

“Then Andy Mackay found this piece of fabric which we used on the inside cover. Nick de Ville, I got him involved, he was a friend from art college. Finding typefaces and fiddling around with that. Then we liked the idea of the (band) pictures looking like postcards. It was a cottage industry, really. We did a session with Karl Stoecker and Antony, dolling us all up. Eno’s girlfriend made a shirt for him – Carol McNicoll, who was a really brilliant artist working in ceramics – she also did his outfits, the feather things later on. Great, like theatre costumes. Andy’s things were a bit more raunchy. Wendy Dagworthy did Phil’s outfit. And Paul was dressed like a caveman – his sound was quite primitive.”

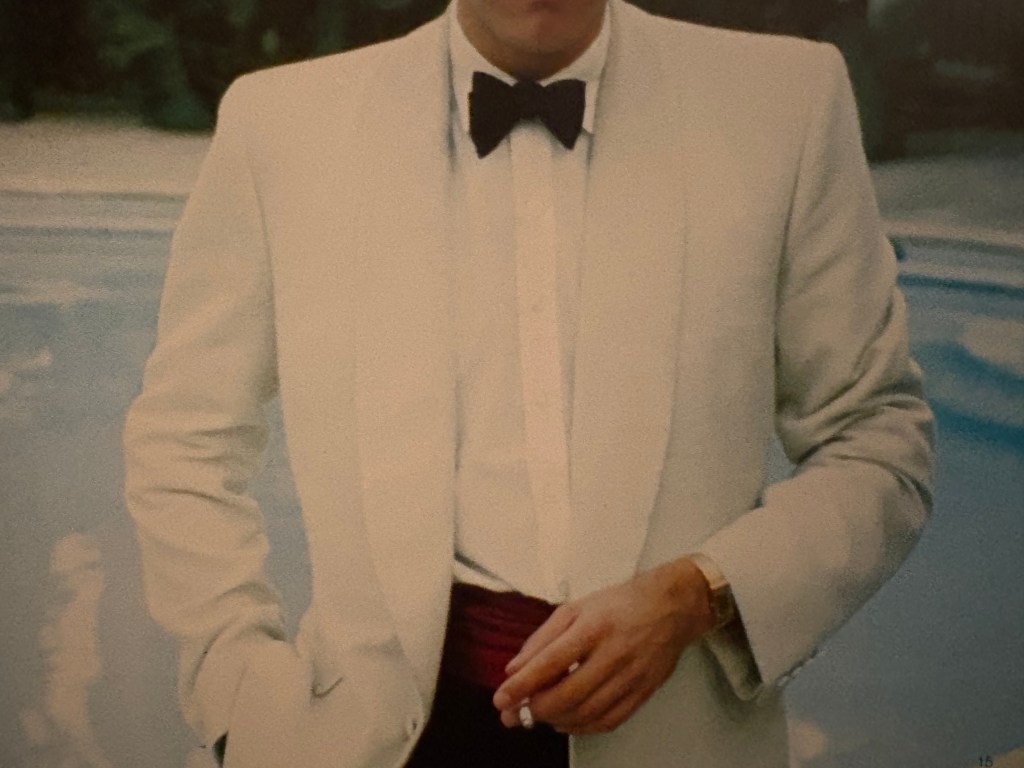

In 1974, for the cover of Another Time, Another Place, Ferry’s second solo album, Antony made two identical white dinner jackets — single-breasted, shawl-collared — for the cover shoot, taken by Eric Boman against a swimming pool, with elegant people in the background. That summer I was going to an Island Records party in the big studio at Basing Street and needed something to wear. Bryan lent me one of those jackets. Nothing has ever felt quite like it.