‘Rhapsody in Blue’ at 100

The first public performance of George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” was given 100 years ago this week, on 12 February 1924, at the Aeolian Hall on West 43rd Street in New York City, by Paul Whiteman and his Concert Orchestra, with Gershwin himself at the piano. Whiteman had commissioned the piece from its composer specially for the evening, which was billed as ‘An Experiment in Modern Music’.

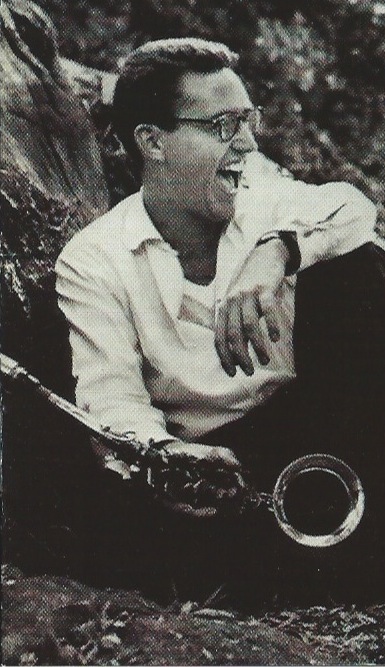

I first heard “Rhapsody in Blue” in childhood, played by the same Whiteman/Gershwin combination, on the 12-inch 78rpm record you see above, which my mother would have bought from a record shop in Barnsley, South Yorkshire, in the 1930s. Nine minutes long, it’s split over both sides of the disc. The gramophone — a Columbia Viva-Tonal Grafonola — is the one on which she played it, along with her other 78s.

To mark the centenary, the pianist Ethan Iverson started a lively debate the other day with a piece for the New York Times in which he examined the artistic impact, then and now, of what he called “a naive and corny” attempt to blend the superficial characteristics of jazz with European classical music. If “Rhapsody in Blue” is a masterpiece, he wrote, it’s surely “the worst masterpiece”: an uncomfortable compromise that blocked off the progress of what would later be called the Third Stream, and with which we are both “blessed and stuck”.

Thanks to my mother’s influence, I view it from a slightly different angle. For me, in childhood, it became a gateway drug. I loved the spectacular clarinet introduction, and the shifting melodies and the hints of syncopation, but more than anything I responded to the tonality that reflected its title, expressed in the exotic flattened thirds and sevenths of the blues scale.

It didn’t take very long before I was following a path that led to Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor, right up to the Vijay Iyers, Matana Robertses and Tyshawn Soreys of today’s jazz. Pretty soon I’d worked out that an ounce of Ellington was worth a ton of Gershwin’s instrumental music*, but I retain a respectful gratitude to “Rhapsody in Blue” and its role as a gateway, just as I do to The Glenn Miller Story and “Take Five”.

A few weeks after the world première Gershwin’s piece, F. Scott Fitzgerald and his young family would set off for France, where he spent the summer knocking the early draft of his third novel into shape. When The Great Gatsby was published the following April, it contained a vivid scene in which the society guests at one of Jay Gatsby’s Long Island parties were entertained by a band described by the author as “no thin five-piece affair, but a whole pitful of oboes and trombones and saxophones and viols and cornets and piccolos, and high and low drums.”

The bandleader — who is unnamed, but it’s easy to imagine him as Paul Whiteman, with his tuxedo, bow-tie and little moustache — makes an announcement. “At the request of Mr Gatsby,” he says, “we are going to play for you Mr Vladimir Tostoff’s latest work, which attracted so much attention at Carnegie Hall last May.” The piece is known, he adds, as “Vladimir Tostoff’s Jazz History of the World”. I’ve always idly wondered what it would sound like, but I imagine Mr George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue”, with its bustling bass saxophone eruptions and flamboyantly choked cymbal splashes, is as close as we’ll get.

* A few people have picked me up on this statement, and I tend to agree with them. I was trying to make a specific point, rather clumsily. George Gershwin was a genius songwriter, as any fule kno.