Heavy makes you happy

When it comes to heavy rock, I draw the line at Jimi Hendrix and the first Vanilla Fudge album: that’s a frontier beyond which I do not choose to venture. But a late-night gig at the Berlin Jazz Festival last weekend persuaded me that the Hedvig Mollestad Trio have found a way to make head-banging feel good.

When it comes to heavy rock, I draw the line at Jimi Hendrix and the first Vanilla Fudge album: that’s a frontier beyond which I do not choose to venture. But a late-night gig at the Berlin Jazz Festival last weekend persuaded me that the Hedvig Mollestad Trio have found a way to make head-banging feel good.

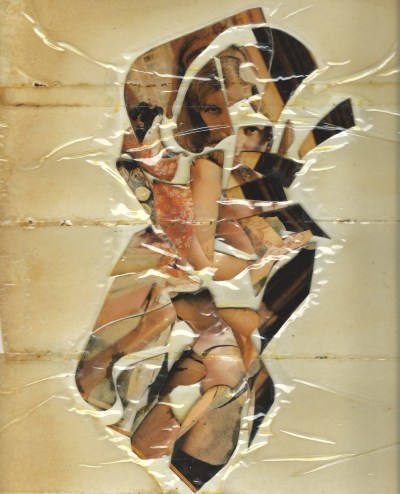

Mollestad, a guitarist with a Valkyrie’s blonde tresses and a sparkly red mini-dress, studied musicology at the University of Oslo before spending five years at the Norwegian Academy of Music. Evidently all that academic training didn’t get in the way of a desire to turn her amp up to 11. She and her trio — Ellen Brekken on bass and Ivar Loe Bjornstad on drums — wail away with such intensity and at such volume that ear-plugs were being offered at the entrance: a first for a jazz gig, in my experience.

I left my hearing unprotected, and I was glad I had. The conditions were ideal: a smallish darkened room with a bar and lots of standing room. It reminded me of the Marquee in the late ’60s, and so did the music — in a good way. The sound of Mollestad’s band might be that of heavy rock, the sort of thing that evolved from the British blues scene of the mid-’60s, but the heart is very different. Yes, there are riffs, but they’re not just riffs. Best of all, nobody tries to sing on top of such a hurricane of sound. And although this is a genre powerfully associated — thanks to a generation of British rockers — with gothic gloom, the trio make it sound like enormous fun (their energy is vivacious rather than bludgeoning), while making it clear that they’re serious about finding a new direction in which to take this music.

Mollestad met Brekken and Bjornstad during her time at the Academy, and all three bring to their work not just a high degree of technical command but a collective sense of imagination and, yes, subtlety. The leader uses her effects pedals to the full, but there’s always something wild and worthwhile happening in her solos, demonstrating a phenomenal deftness and gift for detail. Brakken plays both electric and acoustic basses with an impressive physicality, and it’s amusing that she drives the band just as hard on the latter instrument. Bjornstad can start a solo like a regular rock drummer, but then he flicks a switch and plays something of which Billy Higgins or Frank Butler would be proud. When they play a ballad, they’re so quiet that you strain forward to catch every nuance, as if that were Bill Evans, Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian up there on the stage.

I wrote about Tony Williams’ Lifetime in a piece on Jack Bruce a week or so back, and that’s the group of which, in some respects, they remind me — along with the early Experience, just a bit. Not at that level of invention, unsurprisingly, but on the right path. Others have made comparisons with John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra, Jeff Beck, Led Zeppelin, Motorhead and Black Sabbath, but I don’t hear those, except in the very crudest terms. I suppose the Trio of Doom, which briefly united Williams, McLaughlin and Jaco Pastorius in 1979, might be a point of comparison, but Mollestad’s band are much less egocentric and actually more genuinely creative within the form.

What’s particularly interesting is to hear this kind of music, traditionally associated with male guitar-hero posturing, completely stripped of its machismo while retaining every ounce of what I suppose one can only call its heaviness. And, naturally, all the better for it.

They’re supporting McLaughlin’s 4th Dimension at the EFG London Jazz Festival on November 20. I don’t expect the Festival Hall will provide as helpful an environment as a small dark room packed with fans, but they’ll give the great man some competition.

* The photograph of Hedvig Mollestad is © Per Ole Hagen. It is used by permission of the photographer, and all rights are reserved. It’s one of a set that can be seen on his website: http://artistpicturesblog.com.