A night at Silent Green

Last summer I was blown away by the latest album from Catherine Christer Hennix, the 68-year-old Swedish-American composer, singer and keyboardist who studied with La Monte Young and Pandit Pran Nath before striking out on her own exploration of sound, light, drones, spirituality and just intonation. Last night I got the chance to see her perform during Berlin’s Maerzmusik festival, at a converted crematorium church in the Wedding district.

Last summer I was blown away by the latest album from Catherine Christer Hennix, the 68-year-old Swedish-American composer, singer and keyboardist who studied with La Monte Young and Pandit Pran Nath before striking out on her own exploration of sound, light, drones, spirituality and just intonation. Last night I got the chance to see her perform during Berlin’s Maerzmusik festival, at a converted crematorium church in the Wedding district.

Now named Silent Green, it’s an octagonal space with two circular balconies. The floor was covered with oriental rugs, on which the majority of the audience reclined or assumed yoga-style positions. Hennix was positioned alongside one wall, seated at a two-manual electronic keyboard, flanked by the mixing equipment and other devices operated by Stefan Tiedje, her sound engineer and computer programmer. The rest of the audience had chairs on the first balcony. Above us in the upper balcony were five brass players: Amir ElSaffar (trumpet), Paul Schwingenschlögl (trumpet and flügelhorn), Hillary Jeffery (trombone), Elena Kakaliagou (French horn), and Robin Hayward (microtonal tuba).

Together they performed a piece called “Raag Sura Shruti”, which began with quiet drones from Henna’s voice and keyboard, gradually increasing in intensity until the brass players joined in, coming and going as the music flowed and ebbed and flowed again. If you wanted a shorthand description, you could say that it was as though Terry Riley’s “Persian Surgery Dervishes” had been reorchestrated by Giovanni Gabrieli for the brass choir he had at his disposal in St Mark’s, Venice in the 16th century.

That part of the concert lasted three hours. Not every member of the audience stayed with it. I was fascinated by the slowly changing colours and the stately arc of the music’s evolving narrative. Sometimes it was very beautiful: lustrous, resonant, ambiguous in its tonal movement (thanks to the use of the non-tempered scale), at one point reaching the sort of lung-crushing decibel count normally encountered in another part of the city at Berghain, the techno club with the world-famous sound system. There were other times, understandably enough, when the underlying drones seemed to be hanging around, waiting for something to happen.

Maybe it was my interest in the arrangement of the moving parts that prevented me from achieving the sort of transcendence that this music is ostensibly about. Perhaps I should have been lying down, eyes closed, on one of the Persian rugs, giving myself up to the waves of sound in a non-analytical way. But that didn’t prevent me from enjoying the experience thoroughly and admiring the music greatly, even if it didn’t quite reach the peaks scaled during the New York concert preserved on last year’s album.

Just when the last drone had diminished to a whisper and almost faded away completely, and the musicians had got up from their balcony seats and left the arena, Hennix took over with a closing 15-minute solo improvisation on the keyboard. As she crunched her fingers and fists on the keys, setting up brief, spidery phrases and then splintering them, I thought of how a Chinese boogie-woogie pianist might sound if invited to play a Philip Glass piano étude on one of Sun Ra’s early electronic instruments — the Rocksichord, wasn’t it? — in the style of Cecil Taylor, with an intermittently malfunctioning power supply. An excellent evening all round.

I suppose I’ve always thought of the man who shouted “Judas!” at Bob Dylan in Manchester in 1966 as a dull-witted denier of truth and progress. To my astonishment, however, after spending the last couple of months listening, on and off, to the 36-disc box of the surviving music from that tour, I’ve come to see things a little differently.

I suppose I’ve always thought of the man who shouted “Judas!” at Bob Dylan in Manchester in 1966 as a dull-witted denier of truth and progress. To my astonishment, however, after spending the last couple of months listening, on and off, to the 36-disc box of the surviving music from that tour, I’ve come to see things a little differently. There’s an interesting new poem by Michael Hofmann in the latest issue of the New Yorker. It’s called “Lisburn Road” and it’s about surveying the scattered detritus of a life. In the final stanza there’s a reference that might be puzzling to some of the magazine’s readers: The ‘Porky Prime Cut’ greetings etched in the lead-off grooves…

There’s an interesting new poem by Michael Hofmann in the latest issue of the New Yorker. It’s called “Lisburn Road” and it’s about surveying the scattered detritus of a life. In the final stanza there’s a reference that might be puzzling to some of the magazine’s readers: The ‘Porky Prime Cut’ greetings etched in the lead-off grooves… It was with regret that I had to leave Hull after only 24 hours of Mind on the Run, the weekend festival celebrating the life and work of Basil Kirchin, the visionary composer who spent three decades in the city, working in complete obscurity until his death in 2005, aged 77.

It was with regret that I had to leave Hull after only 24 hours of Mind on the Run, the weekend festival celebrating the life and work of Basil Kirchin, the visionary composer who spent three decades in the city, working in complete obscurity until his death in 2005, aged 77.

There’s an hour-long Arena documentary about Chrissie Hynde on BBC4 this week. During a preview of a longer 90-minute version the other day, I remembered that what I always liked about her was the subtlety underlying the ferocious four-piece rock and roll attack of the Pretenders’ music. It was present in February 1979, when — at the urging of my friend and Melody Maker colleague Mark Williams — I went to see them at the Railway Arms in West Hampstead, a room once known as Klooks Kleek but then renamed the Moonlight Club.

There’s an hour-long Arena documentary about Chrissie Hynde on BBC4 this week. During a preview of a longer 90-minute version the other day, I remembered that what I always liked about her was the subtlety underlying the ferocious four-piece rock and roll attack of the Pretenders’ music. It was present in February 1979, when — at the urging of my friend and Melody Maker colleague Mark Williams — I went to see them at the Railway Arms in West Hampstead, a room once known as Klooks Kleek but then renamed the Moonlight Club.

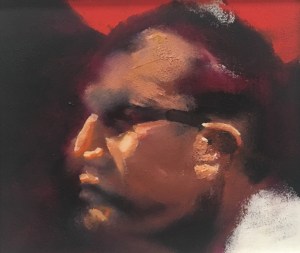

It came as a bit of a surprise to walk into a high-end London art gallery this week and discover a small portrait of Arthur Brown, the madcap rocker of the late ’60s, taking its place in an extensive exhibition of the work of the late English painter Michael Andrews.

It came as a bit of a surprise to walk into a high-end London art gallery this week and discover a small portrait of Arthur Brown, the madcap rocker of the late ’60s, taking its place in an extensive exhibition of the work of the late English painter Michael Andrews.

Dennis Coffey is still playing Tuesday nights at a Detroit club called the Northern Lights Lounge. It’s what he and his 1963 Gibson Birdland have been doing for the best part of 50 years. He started making a local reputation as a session man in the mid-’60s when he played on Darrell Banks’s “Open the Door to Your Heart” and the classic sides on the Golden World label by J. J. Barnes and others. Later in the decade he was absorbed into the Motown studio band, adding the rock-influenced sounds of a wah-wah pedal and a fuzz box to the more classic approaches of the established Hitsville USA guitarists: Robert White, Eddie Willis and Joe Messina.

Dennis Coffey is still playing Tuesday nights at a Detroit club called the Northern Lights Lounge. It’s what he and his 1963 Gibson Birdland have been doing for the best part of 50 years. He started making a local reputation as a session man in the mid-’60s when he played on Darrell Banks’s “Open the Door to Your Heart” and the classic sides on the Golden World label by J. J. Barnes and others. Later in the decade he was absorbed into the Motown studio band, adding the rock-influenced sounds of a wah-wah pedal and a fuzz box to the more classic approaches of the established Hitsville USA guitarists: Robert White, Eddie Willis and Joe Messina. With three hours to go until the inauguration of Donald J. Trump as the 45th president of the United States, the coffee shop I frequent was playing the Staple Singers’ “Respect Yourself”. That’s a record with a lot of American history in it, one way and another: a message delivered by a mixed group of black and white singers and musicians, showing how music can provide encouragement, comfort and even guidance.

With three hours to go until the inauguration of Donald J. Trump as the 45th president of the United States, the coffee shop I frequent was playing the Staple Singers’ “Respect Yourself”. That’s a record with a lot of American history in it, one way and another: a message delivered by a mixed group of black and white singers and musicians, showing how music can provide encouragement, comfort and even guidance.