Lio sings Caymmi

Every now and then an album wanders in and becomes part of the furniture, always there in times of need. Lio Canta Caymmi, an album of songs by the Brazilian composer Dorival Caymmi interpreted by the Portuguese singer Lio, seems likely to become one of those.

Curiously, its predecessors for me include two albums of Brazilian music by female singers: The Astrud Gilberto Album from 1965 and Paula Morelenbaum’s Berimbaum from 2004. It’ll take a couple of years before I can be sure that Lio Canta Caymmi shares their status, but on the basis of a few weeks’ listening to an advance copy, I’ve got a feeling that it will.

The album was the idea of Jacques Duvall, a French lyricist who has worked with Lio and many other artists. Caymmi, who died in 2008 at the age of 94, was a key figure in the establishment of Brazilian popular music in the twentieth century. Although not as well known outside Brazil as Tom Jobim, his songs — many of them written in his twenties — helped lay the foundations for the arrival of bossa nova in the 1960s. Duvall enlisted the aid of his compatriot Christophe Vandeputte to create new settings that employ modest means — guitar, accordion, bass, drums, percussion, the occasional wash of synthesised strings — with great sensitivity.

Lio — born Vanda Maria Ribeiro Furtado Tavares de Vasconcelos in Lisbon — was a pop star in France and Belgium in the 1980s before becoming a film actress. Her earlier musical collaborators included Telex, Sparks and John Cale, but the extroversion apparent on YouTube clips from those days is held in check here. Her delivery of lovely songs such as “Tão Só” and “É Doce Morrer No Mar” (also a favourite of the late, great Cesária Évora) is restrained and unaffected, allowing the gentle, beautifully shaped melodies to shine through, along with the extra verse in French tacked on to each of the original Portuguese lyrics by Duvall. The arrangements include the occasional surprise: the beach sounds and laughter prefacing “Sábado em Copacabana”, a dab of organ making a late entry to underpin the delicate funky groove of “Nunca Mais”, hand-drums animating the humming bossa of “Samba da Minha Terra”.

Nothing here is going to rearrange your life, but it forms a graceful, imaginatively conceived and beautifully executed tribute to a great figure in Brazilian culture. And when you want to let a little sunlight into the room, it might be just the thing.

* Lio Canta Caymmi is released on March 30 by Crammed Discs. The photograph of Lio is by Jane Who.

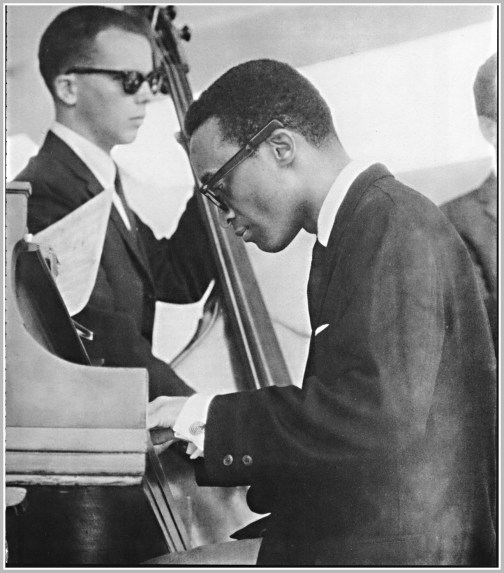

In the summer of 2000 I spent an hour across a table from Keith Jarrett in a rooftop restaurant overlooking the Baie des Anges in Nice. Infuriatingly, he chose to conduct the conversation while wearing mirror shades. An interviewer tries to establish some kind of rapport with his/her subject, in which eye contact plays a part; the shades meant that I spent the hour staring at reflections of myself. I thought it was discourteous, and possibly a bit passive-aggressive. Somewhat wryly, I thought back to the morning 30 years earlier when he had wandered unannounced into the offices of the Melody Maker, a couple of days after his appearance with Miles Davis at the Isle of Wight, hoping to persuade someone to interview him.

In the summer of 2000 I spent an hour across a table from Keith Jarrett in a rooftop restaurant overlooking the Baie des Anges in Nice. Infuriatingly, he chose to conduct the conversation while wearing mirror shades. An interviewer tries to establish some kind of rapport with his/her subject, in which eye contact plays a part; the shades meant that I spent the hour staring at reflections of myself. I thought it was discourteous, and possibly a bit passive-aggressive. Somewhat wryly, I thought back to the morning 30 years earlier when he had wandered unannounced into the offices of the Melody Maker, a couple of days after his appearance with Miles Davis at the Isle of Wight, hoping to persuade someone to interview him.

The architect Nicholas Hawksmoor completed St George’s, Bloomsbury, one of his half-dozen London churches, in 1730, at a time when the transport of slaves from Africa to the New World was booming, with Britain the biggest trafficker. It was built to serve a prosperous parish, although its tower can be glimpsed in the background of Hogarth’s ‘Gin Lane’ engraving of 1751, the artist’s depiction of the low-life inhabitants of the Rookery, as the tenements of nearby St Giles were known. More recently, in 1937, the church welcomed Emperor Haile Selassie at a requiem for the dead of the Second Italo-Abyssinian war, a particularly bloody three-year conflict featuring the use of mustard gas by Mussolini’s troops on the Ethiopian army.

The architect Nicholas Hawksmoor completed St George’s, Bloomsbury, one of his half-dozen London churches, in 1730, at a time when the transport of slaves from Africa to the New World was booming, with Britain the biggest trafficker. It was built to serve a prosperous parish, although its tower can be glimpsed in the background of Hogarth’s ‘Gin Lane’ engraving of 1751, the artist’s depiction of the low-life inhabitants of the Rookery, as the tenements of nearby St Giles were known. More recently, in 1937, the church welcomed Emperor Haile Selassie at a requiem for the dead of the Second Italo-Abyssinian war, a particularly bloody three-year conflict featuring the use of mustard gas by Mussolini’s troops on the Ethiopian army.