On Kate Mossman’s ‘Men of a Certain Age’

(For the last decade and a half, Kate Mossman has written clever, funny, perceptive and quite candid interviews with ageing rock stars. They are, she admits, her speciality. Discussing Journey’s Steve Perry, she says: “I was drawn to him for his ageing vulnerability, his giant ego and his extreme oddness… the perfect combination for me.” She’s just published a collection of the interviews, with commentary and reflections. But I wasn’t very interested in my own opinion of her book. I wanted to know what a woman music journalist of my generation, who interviewed some of the same musicians when they were in their young prime, and for whom being hit on by male musicians was a largely unremarked fact of life, made of the views of a woman born in 1980. So I invited a friend whom I first met in 1969, when I’d just arrived at the Melody Maker and she was already well established along the corridor at Disc & Music Echo, to read the book and, if so moved, to give me her thoughts. She said yes, and here they are. — RW)

By CAROLINE BOUCHER

Is it a good idea to meet your heroes? I’ve met most of mine and the jury’s still out, and I think it’s probably the same for Kate Mossman.

In Men of a Certain Age Mossman meets 19 of them – pieces previously published in The Word and the New Statesman. The subjects are all elderly, as were those chosen by Rolling Stone’s founding editor, Jann Wenner, when he published a selection of interviews claiming, justifiably, that only in their senior years do rock stars attain articulacy and eloquence (and, rather more controversially, that no women at all qualified under those criteria).

Mossman kicks off with the unashamed obsession with Queen’s drummer, Roger Taylor, that meant her teenage family holidays in Cornwall became a pilgrimage to every site connected with him, so that when she was finally granted an interview at his house she could have found it blindfold. Fortunately she reeled away from that confrontation still enamoured.

As she points out: “Rock journalism is unique in that it’s the only place where writers are also obsessive fans, though part of the art is pretending not to be.” A chunk of her early wages was spent on airfares to America where she’d travel to gigs by Greyhound buses or, in the case of a 5,000-mile pilgrimage to meet Glen Campbell in California, walking for three hours down the edge of a freeway.

I’m in awe of her fluid writing style, and jealous of the editorial freedom that now allows her to tell it like it is. By the time she meets Gene Simmons, Kiss have been in the business for 44 years. She likens his hair to “loft insulation”. Or on Trans-Siberian Orchestra’s Paul O’Neill (I know, who he?), who has amassed an extraordinary collection of first-edition books (one signed by Queen Victoria to Kitchener): “He wanders out on to the patio, where the sun beats down so strongly that he must be melting in his leathers… and for a moment he epitomises the contradiction at the heart of rock ‘n’ roll wealth: the baby boomers who bought the lifestyles of the landed aristocracy but insist on looking like pickled versions of the boys they were when they first picked up a guitar.”

Her subjects are a fascinating mix – not all of them out front onstage. For me, the most interesting was Cary Raditz, Joni Mitchell’s former lover and “mean old daddy” from “Carey”, the song named after him. It’s a vivid and fascinating portrayal of the two characters– who initially lived in a cave, and drifted in and out of each other’s lives as Mitchell’s star ascended.

When I was on a music paper in the late Sixties we helped peddle lies. I can still feel the boiling disappointment after an interview with the Byrds who were rude, arrogant and condescending, yet I wrote a bland piece. Syd Barrett was slumped out cold for the entire hour of my interview slot; he couldn’t utter a word. I can’t remember how I got round it, but my editor insisted on filling half a page and afterwards EMI sent me a congratulatory telegram.

An Engelbert Humperdinck review bore no mention of his chauffeur chasing me down the seafront to bring me back for some “entertainment’” Nor did a Mick Jagger interview betray my difficulty taking shorthand notes as his head was resting on my (fully clothed) chest.

As Mossman is meeting her idols in the twilight of their careers the testosterone has ebbed somewhat, although Kevin Ayers gives it a half-hearted try at his dusty French home. His self-belief seemed to be as strong as ever and I can wholeheartedly attest to how irritating he was when I had briefly turned gamekeeper from poacher and was doing PR for Elton John’s office. At the time Elton’s manager, John Reid, signed Ayers, so I flew some journalists out to Paris to see him perform and then talk to him over supper. I knew things were about to go spectacularly wrong when, from my balcony seat, I could see a blonde, cloaked figure at the side of the stage and recognised Richard Branson’s wife, Kristen, with whom Ayers was having an affair. We were spared a Daily Mail front page as fortunately none of the hacks knew who she was and were anyway spared interviews as he went straight back to the hotel with her.

Mossman’s original interviews are pre-Covid, each topped with an explanatory introduction, and many of the subjects have since died, but it’s an excellent read. Previously I had had no interest in many of her heroes — Terence Trent D’Arby, Bruce Hornsby, Jon Bon Jovi, and I’d never even heard of the Trans-Siberian Orchestra — yet those, for me, were the most interesting and insightful pieces.

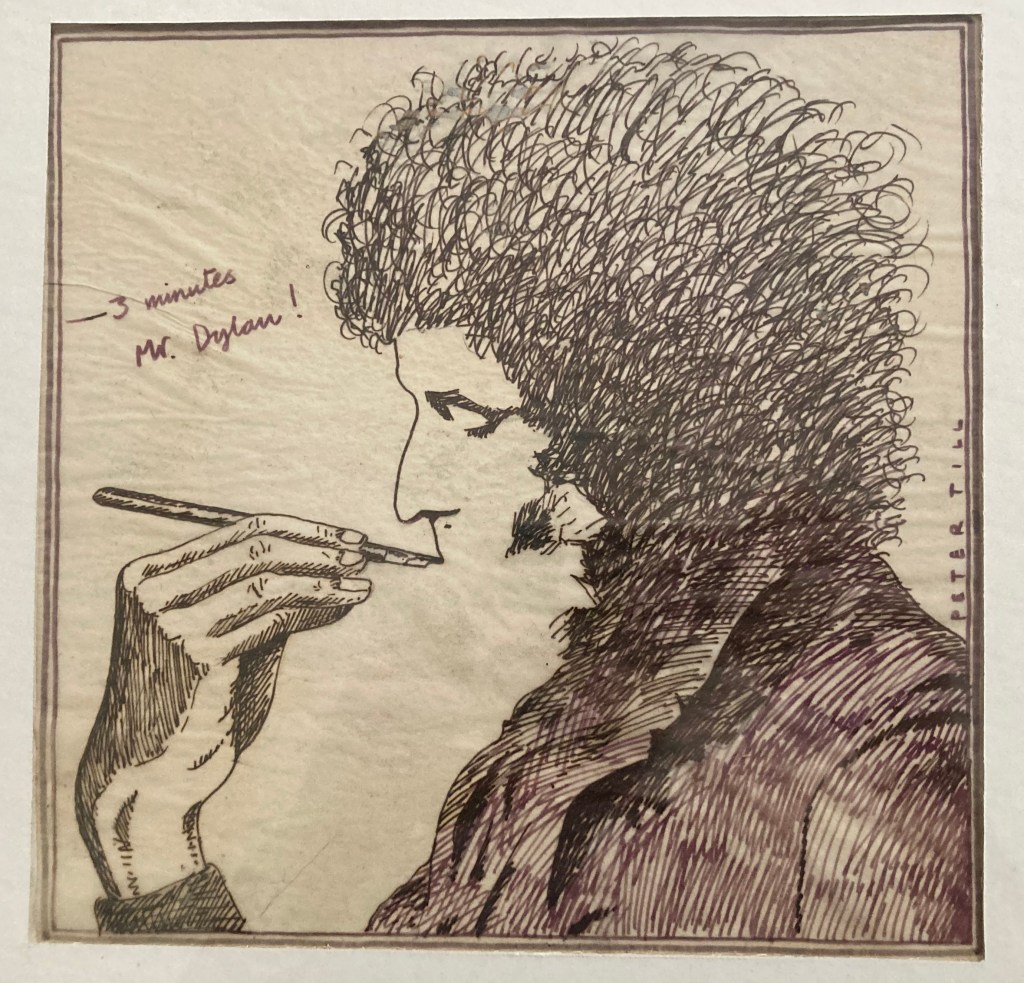

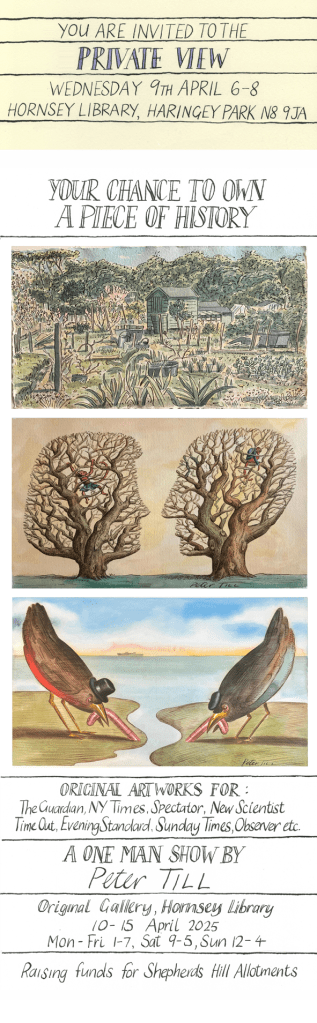

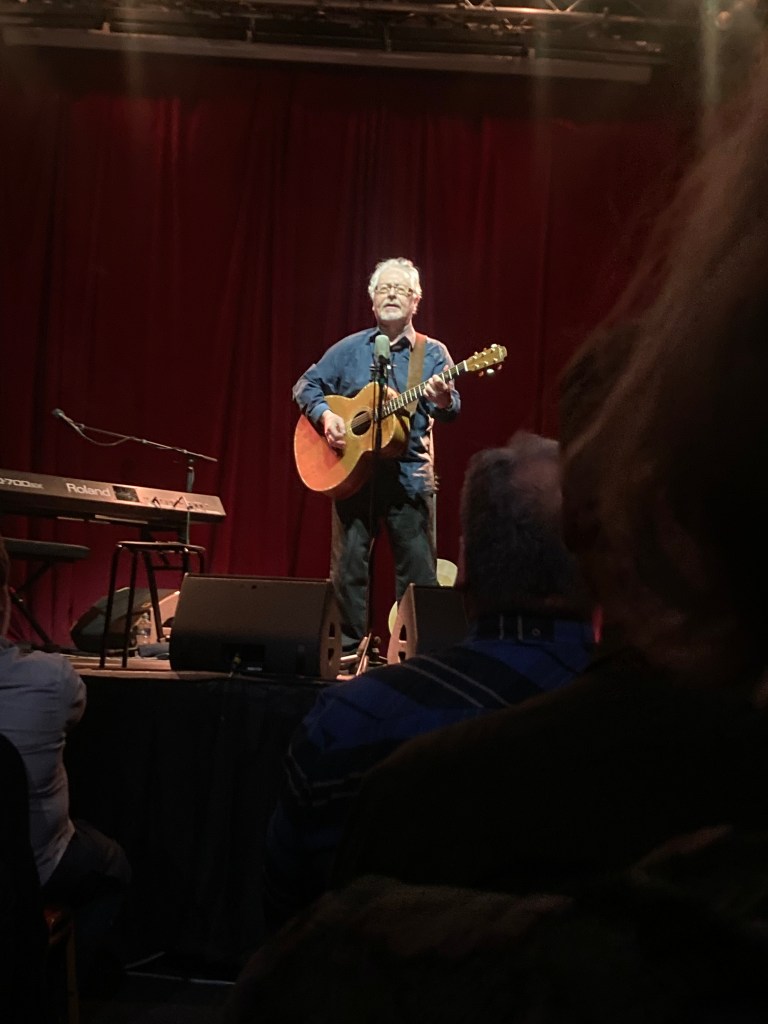

* After Caroline Boucher left Disc, she worked at Rocket Records and was then for many years at the Observer. Kate Mossman’s Men of a Certain Age is published by Nine Eight Books (£22). The photograph of Mossman with Kiss is from the book jacket.