The essential Terri Lyne Carrington

What does it mean when a critic describes an album as “essential”? After all, you can live a full and satisfying life without ever hearing A Love Supreme, Eli & the Thirteenth Confession or Blood on the Tracks, all of which would justify the conventional use of that epithet. But sometimes it’s the word that’s closest to what you want to suggest. And that’s how it is with Waiting Game by Terri Lyne Carrington + Social Science, an album which looks deep into the soul of 21st century America and comes up with something that, like all the best protest music, locates sparks of hope amid the darkness and despair it portrays.

For those unfamiliar with Carrington, she is a 54-year-old drummer, composer and bandleader noted for her work with Cassandra Wilson, Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock and many others. She began playing drums at home in Massachusetts, aged seven, on a kit handed down from her grandfather, who had played with Fats Waller. At 11 she received a scholarship to Berklee College of Music in Boston; at 18 she was in New York and playing at the highest level.

Waiting Game is a suite that, blending songs of protest with cutting-edge African American music, takes its place in the line stretching from Max Roach’s We Insist: Freedom Now Suite through Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On to Ambrose Akinmusire’s Origami Harvest. To the core six-piece Social Science band — Debo Ray (vocals), Kassa Overall (MC), Morgan Guerin (saxophones, bass, EWI), Matthew Stevens (guitar) and Aaron Parks (piano and keyboards) — Carrington adds guest appearances from singers, rappers and MCs including Mark Kibble, Rapsody, Meshell Ndegeocello, Raydar Ellis and Maimouna Youssef, plus the trumpeter Nicholas Payton, the bassists Esperanza Spalding and Derrick Hodge, and others.

The songs are contributed by all the members of the group. Although the words — dealing with oppression and the rights of women, gay people, Native Americans, political prisoners (in the widest definition of the term) and others — are often confrontational, the music is easy to love. The grooves are slinky, the textures have a warm glow, the voices often soothe and seduce. While Rapsody fires up “The Anthem” with righteous fervour, Debo Ray croons Joni Mitchell’s “Love” (which applies gender reassignment to the famous verses from 1 Corinthians Ch. 13) with the sweetness of a Minnie Riperton. Stevens’s lucid guitar improvisations are a frequent delight, particularly on his own composition “Over and Sons”, which runs on the kind of perfectly lubricated rollers that would have Donald Fagen purring.

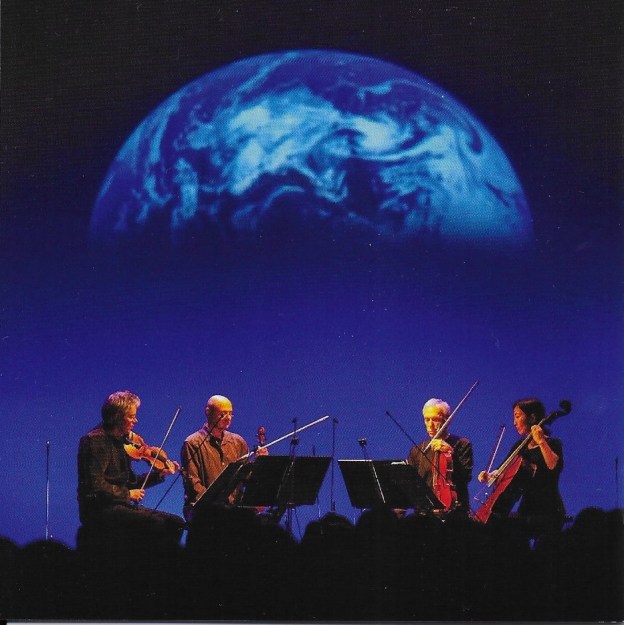

That’s the first CD. There’s a second, containing a 42-minute instrumental suite in four sections, titled “Dreams and Desperate Measures”. It seems to have been improvised by Carrington, Parks, Stevens, Guerin and Spalding, with the addition of a very spare orchestration — by Edmar Colón — for three violinists, a cellist, a clarinetist and a flautist. Ebbing and flowing quite beautifully, slowly changing with the light, it quietly compels the listener’s attention. You feel like you’re sitting in the middle of an intimate conversation, or — in places — a chamber-music version of Bitches Brew.

“Music transcends, breaks barriers, strengthens us, and heals old wounds,” Carrington says in a statement accompanying the album. If that’s a proposition which can ever be proved, here — in an album as good as anything I’ve heard all year — is some persuasive evidence.

* Terri Lyne Carrington will be at Kings Place on Saturday as part of the EFG London Jazz festival, she and Social Science Community performing Waiting Game at a 7pm concert before being joined by British guests — including the saxophonist Soweto Kinch and the trumpeter Emma-Jane Thackray — for a 9pm show. Information: efglondonjazzfestival.org.uk