The Japanese for ‘pathos’

The hip Sonny Clark album, as everyone knows, is Cool Struttin’, a quintet date from 1958 which has come to epitomise what we think of as the Blue Note style: relaxed but compact hard bop, rooted in a deep swing and with the blues never far away. Clark died of a heroin overdose in 1963, aged 31, with nothing to his name beyond his appearances on some exceptional recordings. He would no doubt be astonished to learn that his most celebrated album would sell over 200,000 copies between 1991 and 2009 — almost 180,000 of those copies in Japan, where Cool Struttin’ mysteriously became one of the biggest jazz albums of all time.

My favourite Clark album is something different: a trio session that didn’t see the light of day until its release in Japan more than three decades after the pianist’s death. Blues in the Night is a comparatively modest effort: only 26 minutes long, or 33 minutes if you count the alternate take of the title track. Presumably that’s why it wasn’t released at the time: simply not enough music to make a full 12-inch LP.

Clark was a fine composer, but Blues in the Night is all standards: “Can’t We Be Friends”, “I Cover the Waterfront”, “Somebody Loves Me”, “Dancing in the Dark”, “All of You”. It’s a supper-club set, with nothing to upset the horses. But it’s also, in its quiet and unassuming way, pure treasure. With the great Paul Chambers on bass and Wes Landers — otherwise unknown to me — on drums, Clark makes his way through these tunes at a variety of comfortable tempos with a wonderful touch perfectly highlighted by the simplicity of the setting. I can listen to it all the way through just concentrating on how he articulates a triad: putting down his fingers in a way that makes the chord far more than three notes being played at the same time, the minute unsynchronisations that make it human. And what he finds, I suppose, is a sweet spot between Bud Powell’s probing, restless single-note lines and the swinging, transparently joyful lyricism of Wynton Kelly. Which is a place I’m very happy to be.

I’m indebted for the Cool Struttin’ sales figure to an extraordinary chapter devoted to Clark in a book by Sam Stephenson called Gene Smith’s Sink, a kind of discursive biographical appendix to The Jazz Loft, an earlier book in which Stephenson gave a detailed history of the rackety loft apartment on New York City’s Sixth Avenue, in what used to be called the Flower District, where the great photographer W. Eugene Smith kept a kind of open house for beatniks and other outsiders, recording all their comings and goings on camera film and reel-to-reel tape. From 1957 to 1965 Smith’s loft was the location of an endless jam session featuring the likes of Thelonious Monk and Zoot Sims. Sara Fishko’s 2015 documentary film, The Jazz Loft According to W. Eugene Smith, is based on the book and is highly recommended.

Clark was a regular at the loft, and in Gene’s Sink the author recounts how Smith’s obsession with recording everything around him — even TV and radio news bulletins — extended to the sound of the pianist barely surviving another overdose. Stephenson himself fell in love with Clark’s playing when hearing another posthumous Blue Note release, Grant Green’s The Complete Quartets with Sonny Clark. He writes about him with enormous sensitivity, piecing together the story of a life that began as the youngest of a family of children in a Pennsylvania town called Herminie No 2, named after the mineshaft that gave the place its reason for existence.

If you’re interested in Sonny Clark’s progress from Pennsylvania coal country via Southern California to the New York jazz scene of the late 1950s, Stephenson’s beautiful piece of writing is the thing to read. And it was while following in Gene Smith’s footsteps to Japan (where the photographer documented the horrendous effects of mercury poisoning on the people of the fishing village of Minamata in the 1970s) that the author came across the ideograms most commonly used by Japanese jazz critics in discussions of Clark’s playing: they can be translated as “sad and melancholy”, “sympathetic and touching”, “suppressed feelings”, and one which combines the symbols for “grieving”, “autumn” and “the heart” to suggest “a mysterious atmosphere of pathos and sorrow”.

That mood isn’t really reflected in my favourite Sonny Clark record. What I hear, funnily enough, is an expression of pleasure in being alive to play the music he loved and for which he had such a precocious talent. I’m guessing he sometimes felt like that, too.

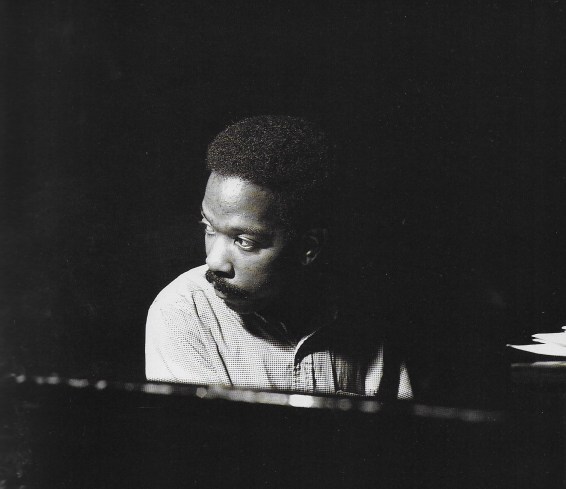

* Sam Stephenson’s Gene’s Sink: A Wide-Angle View was published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2017. The Jazz Loft Project was published by Knopf Doubleday in 2012. The portrait of Sonny Clark is from Blue Note Jazz Photography of Francis Wolff, by Michael Cuscuna, Charlie Lourie and Oscar Schnider, published by Universe in 2000 (photo © Mosaic Images). Clark’s Blues in the Night was first released in Japan in 1979 and issued on CD in 1996. The tracks are also available on Clark’s Standards CD, released in 1998.