Finding Lulu

Lulu was on a breakfast TV show the other day, talking about overcoming a drink problem that had its roots in her family background. She was engaging enough to make me want to read her newly published autobiography, If Only You Knew. Compiled with the help of a ghostwriter, Megan Lloyd Davies, it’s quite a surprise. Its 76 short chapters, plus prologue and epilogue, are not just extremely readable but full of interesting observations from a long career.

I was never a fan of her singing, but I’m a considerable fan of two of her songwriting efforts. They come from the opposite ends of the emotional spectrum. The first is “I Don’t Wanna Fight”, a hit for Tina Turner in 1993, a great pre-breakup song full of complex grown-up feelings — resignation, defiance — to which Tina could bring a sense of her own history. The second is “My Angel Is Here”, a track from Wynonna Judd’s 1996 album Revelations, a luminous love song of perfect simplicity.

Lulu didn’t write those songs alone. Her brother Billy Lawrie worked with her on both, with contributions from Steve DuBerry in the first case and Mark Stephen Cawley in the second. My guess is that, since she doesn’t play an instrument, her main contribution was to the lyrics. Anyway, they’re two of the best tracks of the ’90s, if you ask me.

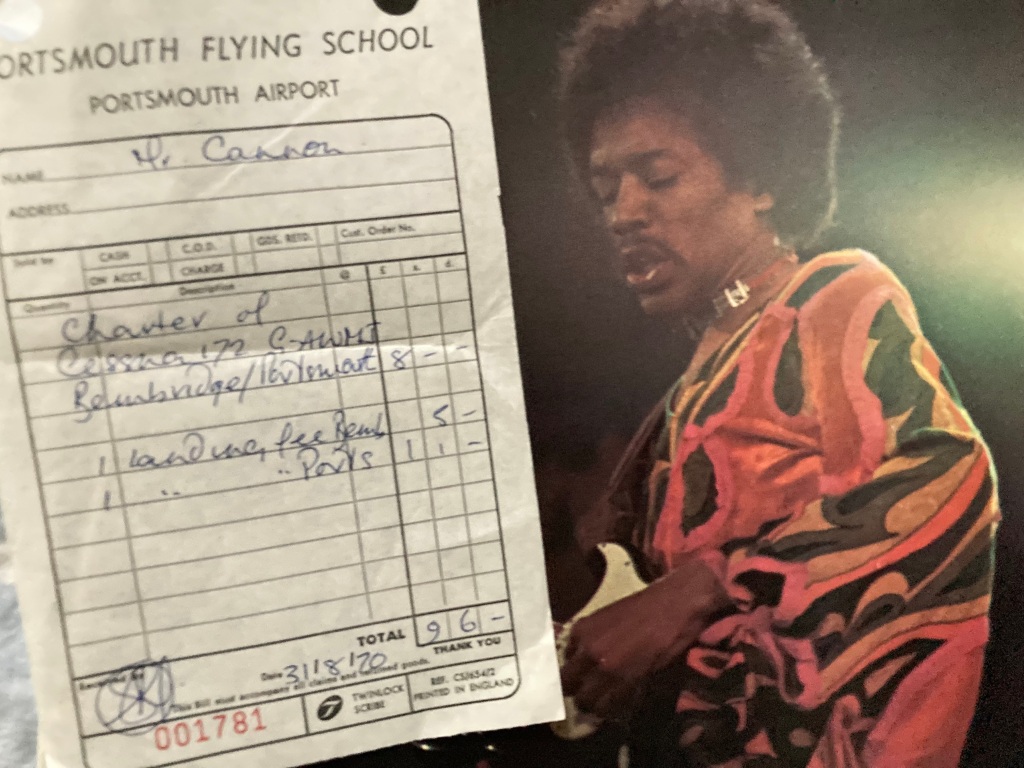

What’s good about her book? Its candid descriptions of her Glasgow childhood, for a start, as Marie Lawrie, the oldest of four children of an alcoholic father; of her audition at Decca in 1963, when the power of her voice blew a microphone; of the resulting decision to move down to London, aged 14, with her band; of her experiences in the ’60s scene, when there the absence of a real division between “rock” and “pop” meant that Jimi Hendrix was a very memorable guest on her Saturday-night BBC TV show; of her short-lived involvement, musical and personal, with David Bowie in 1973. And of her inability to say no to the schemes dreamed up by her devoted manager, Marian Massey, who steered her resolutely towards light entertainment and mostly away from the stuff she wanted to sing, resulting in pantomime seasons and the Eurovision-winning “Boom Bang-a-Bang”, which she clearly detested.

For me, the most interesting section deals with her experiences with Atlantic Records, to whom she was signed by Jerry Wexler in 1970 and with whom she recorded two albums, New Routes and Melody Fair, at Muscle Shoals and Miami’s Criteria Studios respectively. She leaves no doubt about how much this meant to her, in terms of moving closer to the music she loved. Wexler choosing the songs, Arif Mardin doing the arrangements, Tom Dowd at the mixing desk, the Swampers and the Dixie Flyers laying down the tracks: it seemed like the answer to her prayers, a guaranteed escape from the middle of the road.

But it didn’t work out, and I was curious enough to listen to tracks from both albums to try and understand why. The song choices aren’t great, which is weird when you consider that Wexler would have had access to material from the finest country-soul writers of the time, people like Dan Penn and Spooner Oldham. But it’s a mish-mash. The real problem, however, is that although Lulu had her first hit with a raucous cover of the Isley Brothers’ “Shout”, she isn’t a soul singer. She’s a pop singer. For all her ability to add a rasp to her voice, she skates across the surface of the songs. It’s not hard to imagine Wexler concluded quite early on that he’d made a mistake. She wasn’t an Evie Sands or a Merrilee Rush, and this wasn’t going to be a repeat of Dusty in Memphis.

The book’s later episodes include a success with Richard Eyre’s Guys and Dolls, touring with Take That, guest-starring in Absolutely Fabulous, and a grim experience on Strictly Come Dancing. And gradually, coming in like layers of cloud, the drinking that took a grip as she went through middle age, finally taking her into six weeks of rehab in an American clinic at the age of 65.

Yes, it’s a bit showbizzy in places, because that’s partly who she is, but she’s honest about things like her two marriages, for instance, which both ended in divorce, and her looks (“some Botox and filler around my jaw, plus some kind of eye lift”). She also at pains not to bore us: she never dwells too long on anything, which keeps the narrative rolling along.

It’s not normally the sort of book I’d choose to spend time with, but I’m quite glad I did. I suppose I was most genuinely moved by the description of how, while still in her teens, she horrified her family and their neighbours by her appearance in a TV soap ad, speaking in a voice from which, after four years in London, all traces of Glasgow had been smoothed away. “I sounded as if I’d grown up somewhere between Cheltenham and Chelsea,” she writes. “The erasure of Marie Lawrie, on the outside at least, was complete.” But, as we discover, that was very much not the whole story.

* Lulu’s If Only You Knew is published by Hodder & Stoughton.