Starless and bible black

To begin at the beginning:

It is spring, moonless night in the small town, starless

and bible-black, the cobblestreets silent and the hunched,

courters’-and-rabbits’ wood limping invisible down to the

sloeblack, slow, black, crowblack, fishingboatbobbing sea.

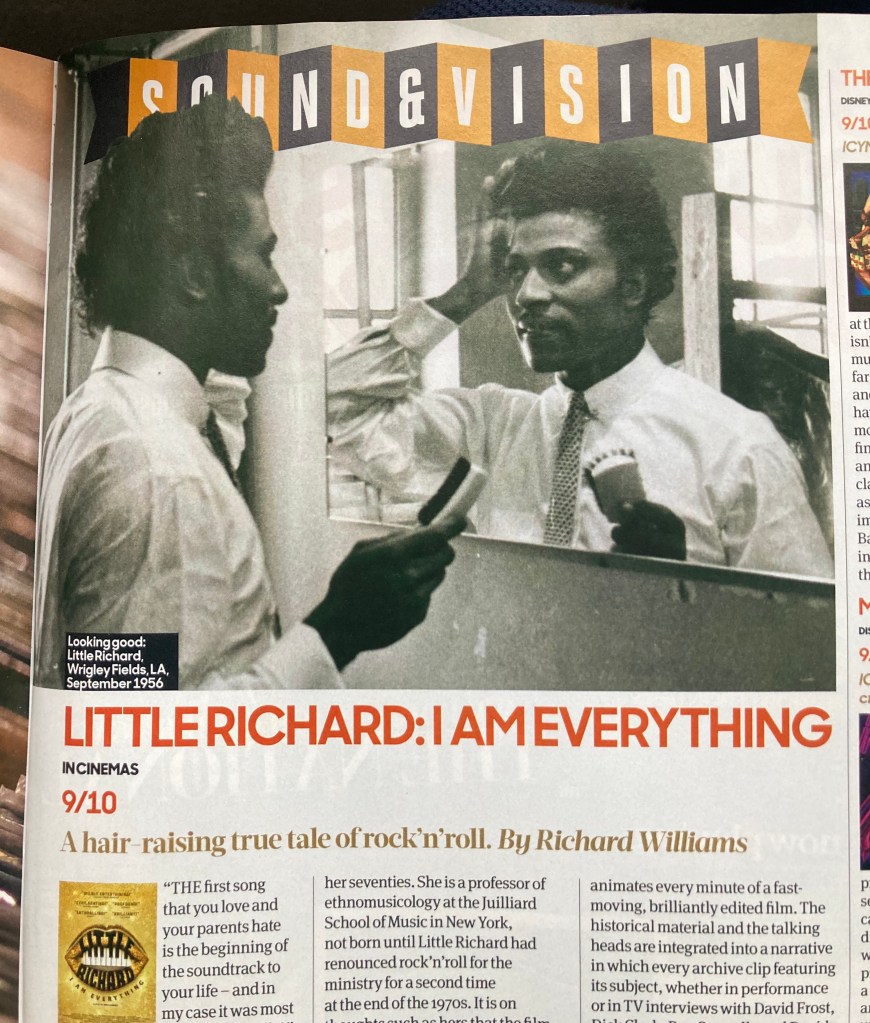

That’s how Dylan Thomas opened Under Milk Wood at his first readings of the drama in 1953. They were presented at venues from the Poetry Centre in the 92nd Street Y in New York City — with a full cast before an audience numbering 1,000 — to a solo performance for a local arts club at the Salad Bowl Café in Tenby on the south-west Wales coast. His health was deteriorating fast and he had died, aged 39, while back in New York for further performances — staying at the Chelsea Hotel, drinking at the White Horse Tavern — by the time Richard Burton read those words the following year in a famous BBC Radio production. Two years later the Caedmon label, which specialised in spoken-word recordings, issued a vinyl double-album of the Poetry Centre production, recorded using a single microphone.

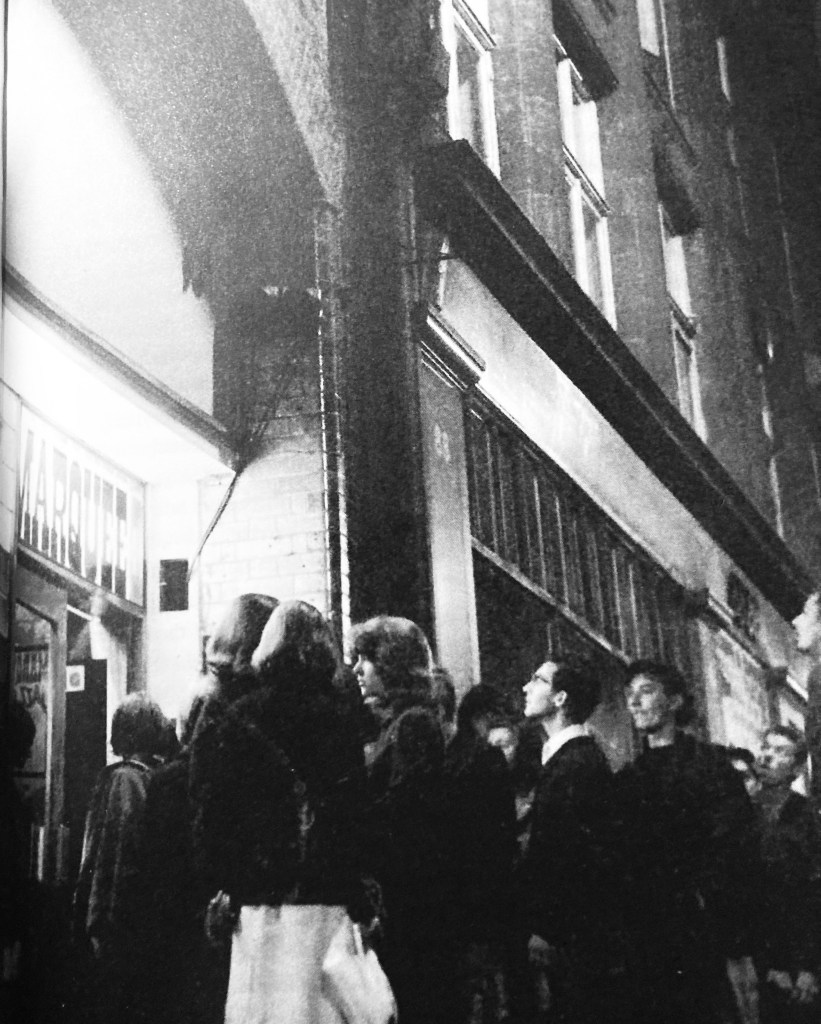

The British pianist and composer Stan Tracey was so impressed by Under Milk Wood that he made it the inspiration for a suite recorded with his quartet in London in 1965. He started by jotting down some titles while listening to the play, then wrote the music to go with them. The producer Denis Preston supervised the recording at his Lansdowne Studios in Notting Hill, and it was released on EMI’s Columbia label the following year, to great acclaim. As an example of jazz arising directly from a literary or dramatic source, it has seldom been equalled.

More specifically, the album contains a track which has sometimes been called the greatest recording in the history of British jazz. That’s a big claim, and probably an absurdly unrealistic one, but the fact remains that “Starless and Bible Black”, the track in question, is a thing of unearthly and profound beauty, its simplicity of means and its relatively brevity (three minutes and 45 seconds) serving only to highlight its extraordinary nature and the intensity of its mood, preserved in a misty penumbra of reverb by the engineer Adrian Kerridge.

Tracey’s gentle outlining of the modal structure (the chords strummed almost as if by a harp), Bobby Wellins’s hushed tenor saxophone, Jeff Clyne’s bowed bass, and Jackie Dougan’s mallets on his tom-toms immediately recall the only possible model for this piece: John Coltrane’s immortal “Alabama”, recorded in 1963. But whereas Coltrane’s sombre threnody was recorded in response to the murder of four schoolgirls in the racist bombing of a church, Tracey’s tone poem issues from very different emotional source. It’s the sound of a small Welsh cockle-fishing village at night, the silence of its dark streets penetrated only by the dreams of its inhabitants — Captain Cat, Rosie Probert, Mrs Ogmore-Pritchard, Dai Bread, the Reverend Eli Jenkins, Organ Morgan and the rest of Thomas’s motley cast.

The remainder of the album consists of seven rather more conventional but still very worthwhile pieces, their titles, including “No Good Boyo”, “Llareggub” and “Cockle Row”, referencing Thomas’s play. Full of spirit and inventiveness, they display Tracey’s creative response to the stimulus of his two primary musical influences, Ellington and Monk. This particular quartet was one of the finest groups of the pianist’s long and illustrious career, affording a particularly welcome chance to listen at length to the marvellous Wellins, who was among the greatest of Scotland’s many distinguished jazz musicians.

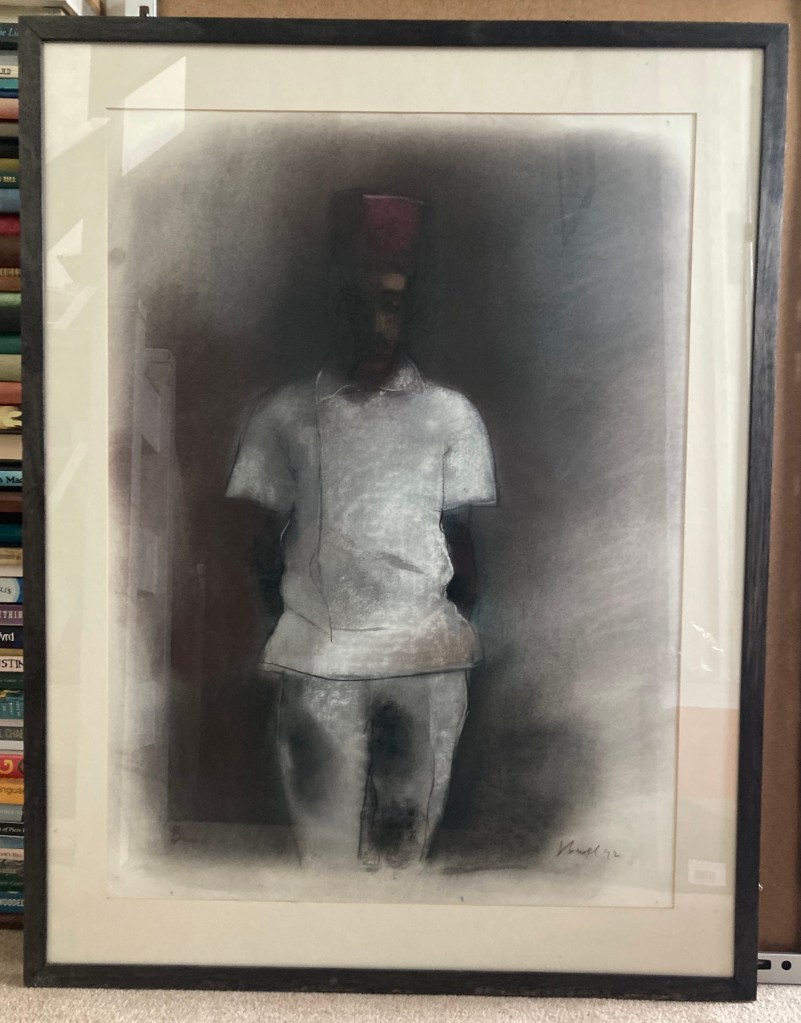

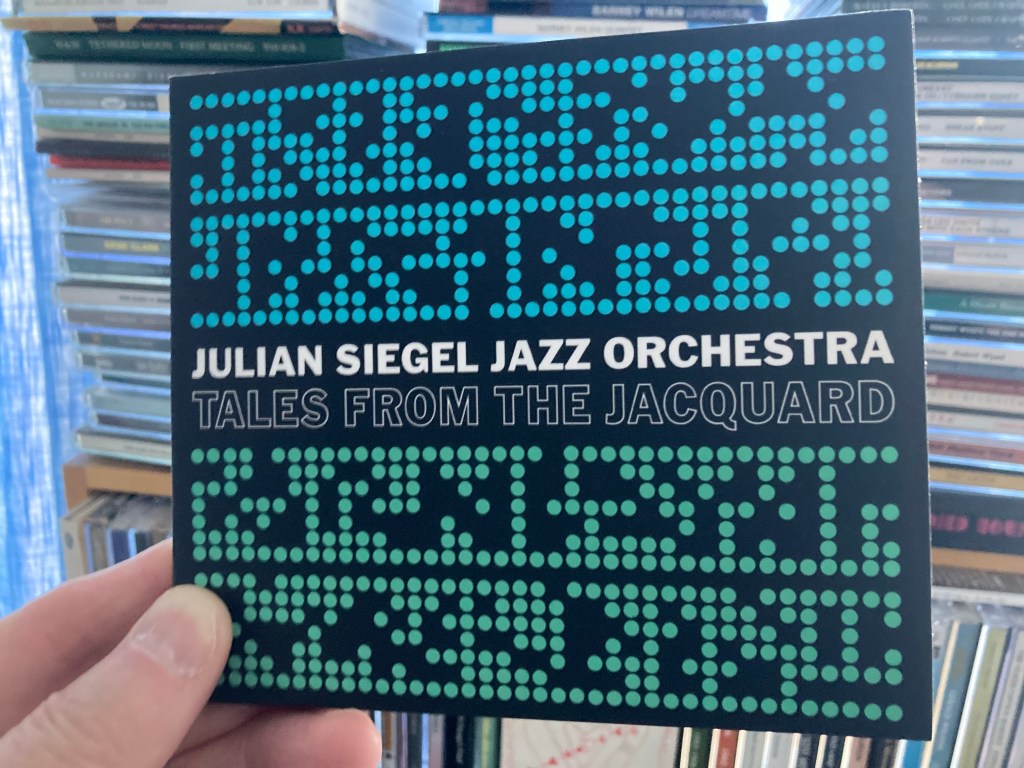

Next Sunday, 14 May, is International Dylan Thomas Day, marking the anniversary — the 70th, on this occasion — of the first performance of Under Milk Wood in New York. I was reminded of this by Hilly Janes, an old colleague at The Times whose artist father, Alfred Janes, was a friend of Dylan’s and painted his portrait at various stages of his career — including, in 1953, the one above. It appears on the cover of Hilly’s excellent and warmly received biography of Thomas, first published in 2014, now in paperback, and containing a vivid description of the poet’s final year. Happily coinciding with the anniversary is the first vinyl reissue of Tracey’s album since 1976, remastered and with a new sleeve note by his son, the drummer and bandleader Clark Tracey.

Hilly also sent me someone’s playlist of other records inspired by Dylan, including John Cale’s “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” and “A Child’s Christmas in Wales”, “Dylan & Caitlin” by the Manic Street Preachers, “Eli Jenkins’ Prayer” by the Morriston Orpheus Choir, Simon and Garfunkel’s “A Simple Desultory Philippic” and, of course, King Crimson’s very different idea of “Starless and Bible Black”. But on Sunday, to accompany the remembrance of a genius, the Stan Tracey Quartet’s album will be all the soundtrack you need.

* The vinyl reissue of Stan Tracey’s Jazz Suite Inspired by Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood is on Resteamed Records. Hilly Janes’s The Three Lives of Dylan Thomas is published by Parthian Books. The portrait of Thomas by Alfred Janes is reproduced by permission of the Harry Ransom Centre, University of Texas at Austin, and is the copyright of the artist’s estate.