The bending of headlights

“We have a new very quiet album out,” Rickie Lee Jones said as she greeted a packed Jazz Café in London last night. I bought Pieces of Treasure, the album in question, a few weeks ago, played it three times, and filed it next to the rest of the evidence of her long and remarkable life in music. It was certainly nice to see her reunited with Russ Titelman, the co-producer of her unforgettable debut album back in 1979 and a careful curator of this new collection of standard songs, but it didn’t make a huge initial impression. Last night she brought it to life.

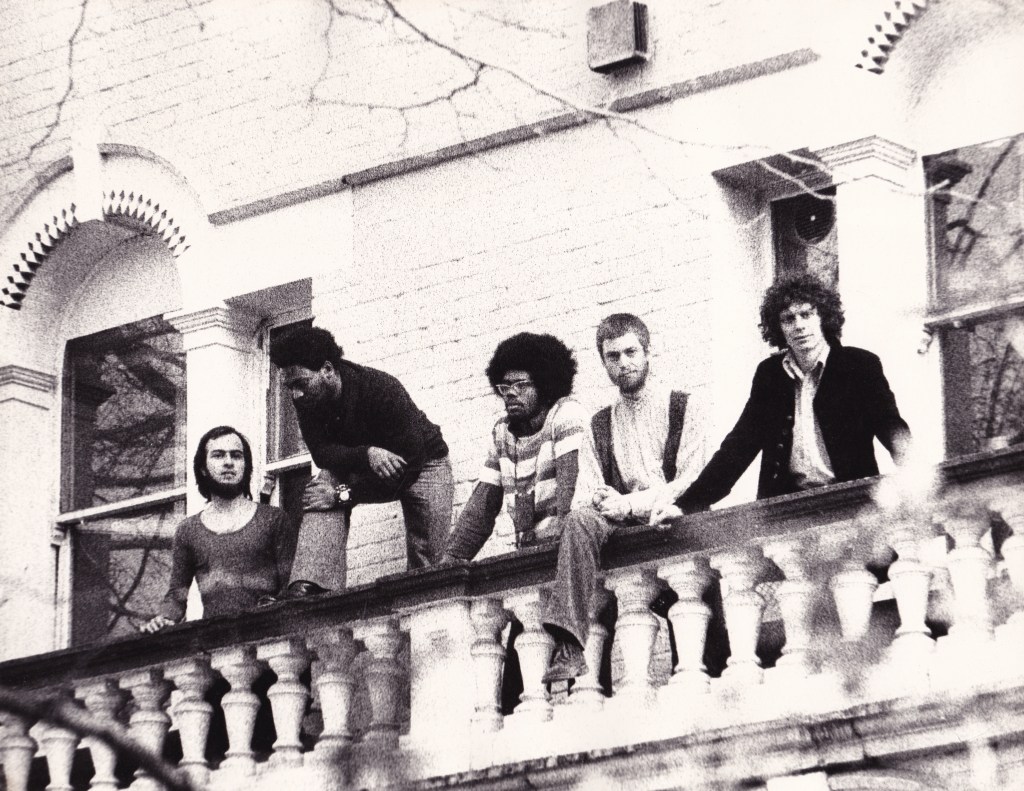

She’s travelling with a three-piece band: Ben Rosenblum on electric piano doubling accordion, Paul Nowinski on string bass and Vilray Bolles on electric guitar. For the first half of the 75-minute set she just sang a selection of standards, starting with a pin-drop “The Second Time Around”, which she recorded on Pop Pop in 1991, and continuing with “Just in Time”, “One for My Baby” and “September Song”, which are on the new one, then “Up a Lazy River” from 2000’s It’s Like This, “Hi-lili, Hi-lo” from Pop Pop (with the accordionist not just exquisitely replicating but actually improving on Dino Saluzzi’s bandoneon part on the original recording), and “Nature Boy” from the new one.

It didn’t take long to appreciate not just how well she was singing but how beautifully her musicians were creating a matrix for the way she was so thoroughly inhabiting the songs. You might have heard “September Song” a million times, interpreted by some of the greatest singers in the history of popular music, but by bringing herself so close to the song, by eliminating the distance between song and singer, she made you think, as if for the first time, about what it meant.

Later on she did the same with another song worn threadbare by repetition. “There will be other lips that I may kiss / How could they thrill me like yours used to do? / Oh, I may dream a million dreams / But how will they come true? / For there will never be another you.” It was as though she’d just written it.

The groove changed with Steely Dan’s “Show Biz Kids”, which she recorded on It’s Like This. The slinky funk-lite keyboard riff summoned a whole universe of laid-back rock and roll hipness, and the audience enjoyed singing along: “Show business kids makin’ movies of themselves / You know they don’t give a fuck about anybody else.” (And how prophetic was that, written by Walter Becker and Donald Fagen 50 years ago?) She did her father’s song, the lullaby-ballad “The Moon is Made of Gold”, and her own much loved “Weasel and the White Boys Cool”, and finished by returning to the new album for “On the Sunny Side of the Street”, a song her dad taught her in the summer of 1963 (“a big year for me” — she would have been eight years old, and he also taught her “My Funny Valentine” and “Bye Bye Blackbird”). She left to an ovation, on a wave of profound affection.

But earlier, after about an hour, when she had strapped on a guitar, there had been “The Last Chance Texaco”. Those two gentle chords, instantly recognisable, then: “A long stretch of headlights / Bends into I-9…” It’s a movie. It’s a poem. It’s a confessional. It’s a communion. It’s the song that defines her. The one that most fully draws us into her world. “(It) wasn’t like anything I’d ever written,” she remembered in her wonderful 2021 autobiography. “It wasn’t like anything I’d ever heard.” As she sang it, once again the space between then and now collapsed. And when the sound of the car on the highway faded to silence, I might not have been alone in discovering that my cheeks were suddenly damp.

* The photo of Rickie Lee Jones at the Jazz Café is by me. Pieces of Treasure is on BMG/Modern. Her autobiography, Last Chance Texaco, is published in paperback by Grove Press. Thanks to Allan Chase (see Comments) for identifying the musicians.