I’ve lived in London since the last days of the 1960s, and I’m still not sure how I feel about it. But there are certainly bits of the city, usually individual streets, where I feel at home. The photo above is of Meard Street, which joins Wardour Street to Dean Street in Soho. If I could, I’d live in one of the Georgian houses on the right-hand side, dating from around 1720. On the left, at No 6, under the blue awning, is the shop of the tailor John Pearse, who opened Granny Takes a Trip at World’s End on the King’s Road in 1966. Beyond it is what was until not all that long ago, and very obviously, a bordello. On the same side of the road, on the corner of Dean Street, was the club first known as Billy’s and then as Gossips, which hosted the weekly Gaz’s Rockin Blues sessions, run by John Mayall’s DJ son, from 1980 to 1995.

That’s the historic London I cherish. Billy’s and Gossips weren’t my scene but on Meard Street I’m a minute or two’s stroll away from the sites of the 2 Is, the Flamingo, the Marquee, the Pizza Express jazz basement on Dean Street, the 100 Club, the Astoria, Les Cousins, Ronnie Scott’s original and current clubs, Bill Lewington’s and Macari’s instrument shops, the record stores of long-gone days — Dobell’s on Charing Cross Road, James Asman’s on New Row, Collet’s on New Oxford Street and its successor, Ray’s Jazz, on Shaftesbury Avenue, One Stop and Harlequin on Berwick Street, and Transat Imports on Lisle Street — and the newsagents on Old Compton Street where you could buy the latest Down Beat.

Two new books — Robert Elms’s Live! and Peter Watts’s Denmark Street — deal, in very different but equally enjoyable ways, with London’s musical history. Elms is best known as a long-standing host on BBC Radio London whose show was unaccountably moved, a couple of years ago, from its daily slot to the weekends. Unlike most people who could be described as professional Londoners, he’s never boring on the subject of his home city. He’s the ideal host: genial without being effusive, genuinely interested in what his guests have to say. And on his show you’re never far away from an excellent piece of music.

He started his career writing for The Face and the NME before becoming a prime mover of the New Romantic movement. We won’t hold that against him. Had he been born 10 years earlier, he would have been a perfect Mod. And his tastes evolved to include all sorts of music, including reggae, jazz, flamenco and tango, all of which he writes about in his new book.

Live! — subtitled Why We Go Out — is an account of his gig-going career filled with the characteristic enthusiasm of a man who describes himself as a gadfly. “I’ve been an honorary member of every passing trouser tribe,” he writes, “sported every silly haircut imaginable and enjoyed almost every style of music, bar heavy metal and opera.”

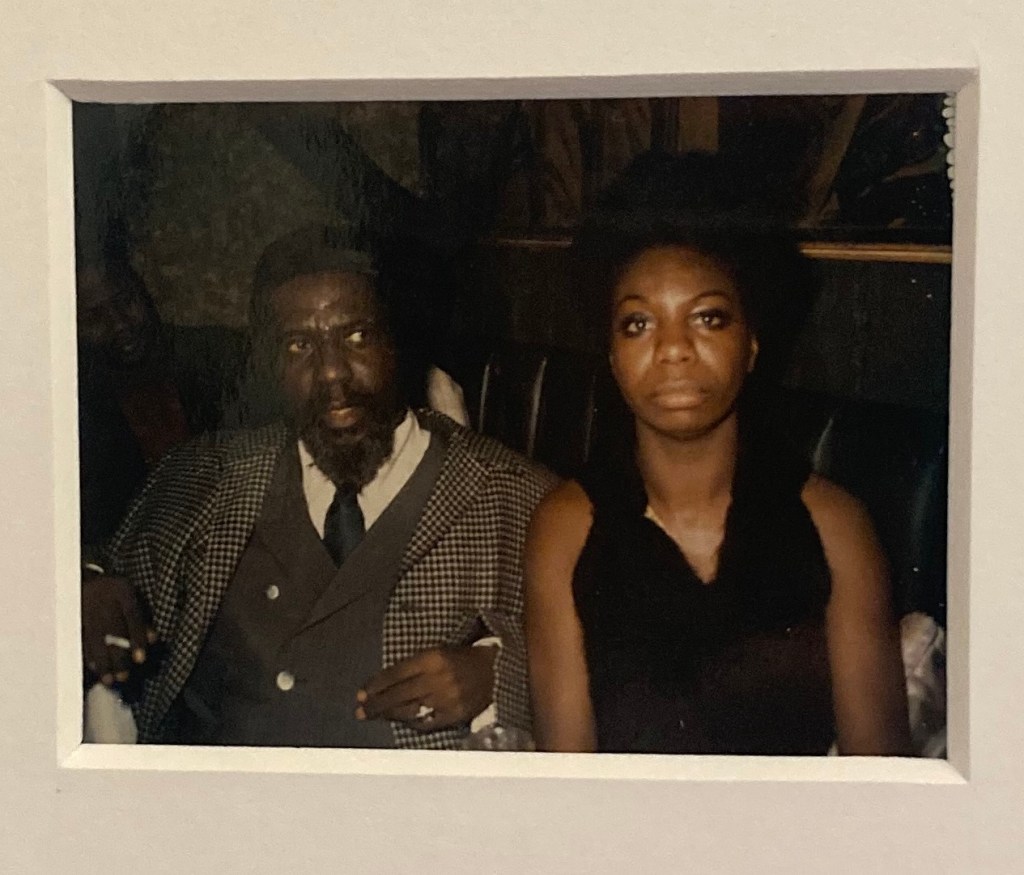

There are chapters on the time he almost became a member of Spandau Ballet, on his life as Sade Adu’s boyfriend when she was on the way up, on the eternal strangeness of Van Morrison, on his affection for and encounters with the Faces, Bruce Springsteen, Tom Waits, Paul Weller, and Gillian Welch and David Rawlings. He felt his life transformed by witnessing the Jackson 5 at Wembley Arena, saw Little Feat at the Rainbow and now regrets that doesn’t remember much about it, turned up to play football with Bob Marley wearing entirely the wrong sort of kit, listened to the young Amy Winehouse sing in his Radio London studio, and attended the last-ever gig by Dr Buzzard’s Original Savannah Band in New York (how I envy that).

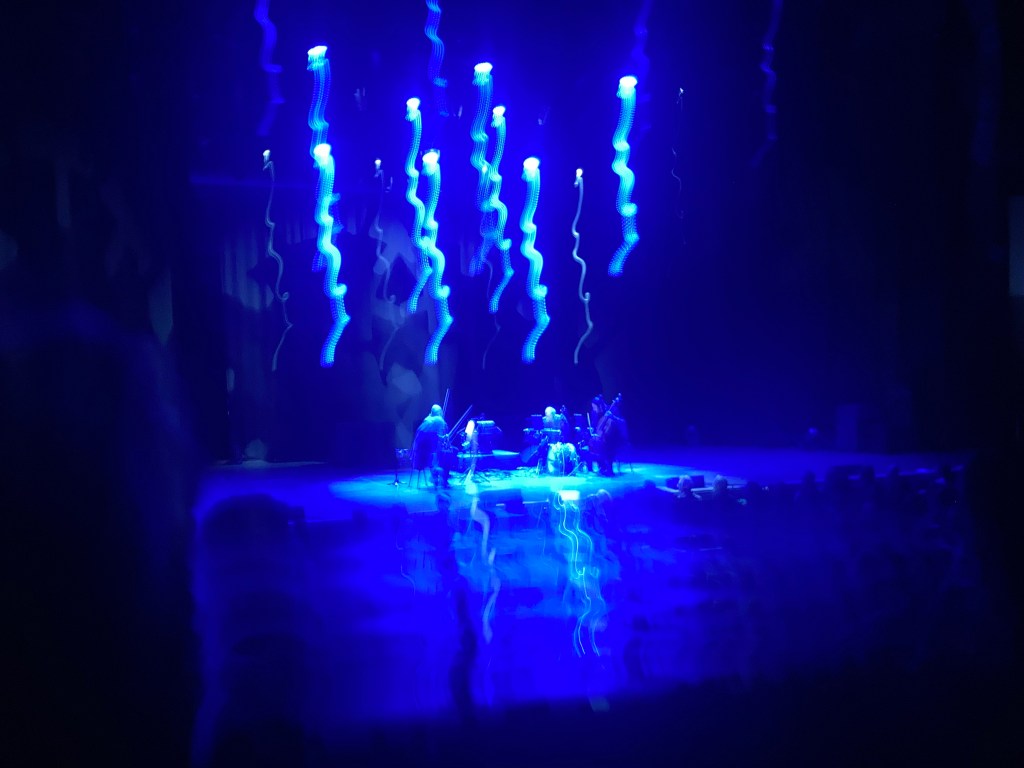

Elms isn’t Lester Bangs or Simon Reynolds. He doesn’t polemicise or analyse. What he’s good at is sharing the thrill of being in the right place at the right time. To me, nowhere is this better conveyed than in his descriptions of falling for flamenco music while living in Spain (he’s sent me off to listen to José Montje Cruz, known as Camarón de la Isla) and the music of Astor Piazzolla while visiting Buenos Aires. Now it’s my turn to make him jealous: when Piazzolla’s Quinteto Tango Nuevo played the Almeida Theatre in Islington for five nights in 1985, I was there for three of them, and the experience was unforgettable.

Peter Watts’s history of Denmark Street is a diligent but also lively and amusing trawl through the origins and evolution of London’s Tin Pan Alley, a narrow street in an area of ill repute in which Lawrence Wright became the first of many music publishers to open an office in 1911. Later, at No 19, Wright would start a weekly paper called the Melody Maker in 1926, followed in 1952 by the New Musical Express, founded by Maurice Kinn at No 5.

Other important addresses on the street were No 9, where a ground floor café called La Gioconda became a meeting place for ambitious young musicians; No 4, where the Rolling Stones recorded “Not Fade Away” and their first album at Regent Sound Studios in 1964; No 24, the home of KPM, specialists in jingles and library music; No 6, where Hipgnosis — Storm Thorgerson and Po Powell — designed elaborate album covers for Pink Floyd and 10cc and where the embryonic Sex Pistols lodged in a back room, later taken over by the embryonic Bananarama; and No 7, where the Tin Pan Alley Club offered a welcome to assorted crooks and gangsters.

Denmark Street: London’s Street of Sound preserves for posterity the story of a piece of London now half-destroyed by a development that has turned the top end of Charing Cross Road into something resembling a cross between Times Square and the Las Vegas Strip: a garish high-tech entertainment facility that could have been born in the imagination of J. G. Ballard at his most dystopian. Like the east side of the bottom end of Charing Cross Road or the east side of Berwick Street, the south side of Denmark Street survives relatively untouched, forced to stare across at its latest iteration.

* Live! by Robert Elms is published by Unbound. Denmark Street by Peter Watts is published by Paradise Road.