In the Unreal City

Snow fell in London yesterday morning. It seemed the right sort of day for a performance of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land at the Queen Elizabeth Hall. Although the poem contains all kinds of weather in all kinds of places, from the cracked earth of endless plains to thunder in the mountains and a summer shower on a Bavarian lake, taking the short walk from Waterloo station in a cold and dark London (the poet’s “Unreal City”) was like strolling straight into its heart.

Mounted as part of the EFG London Jazz Festival, the performance offered an expanded version of the treatment commissioned 10 years ago by the Beckett festival in Enniskillen from the Irish actor Adrian Dunbar. With the permission of the famously strict Eliot estate, Dunbar was able to devise an arrangement of the poem for four actors (two women and two men) plus a jazz quintet playing music by the saxophonist and composer Nick Roth.

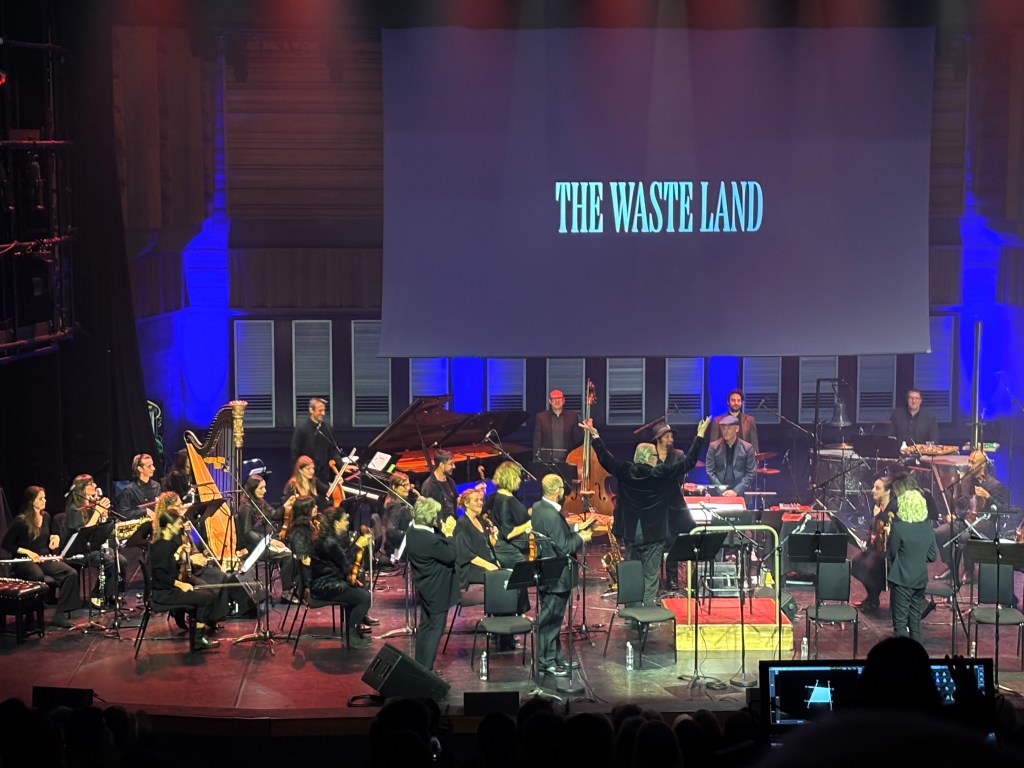

I was 15 when an English teacher named Keith Yorke took us through The Waste Land, decoding its mysteries. I could never thank him enough. Dunbar, introducing last night’s performance, in which the quintet was augmented by a 25-piece orchestra, said he had encountered it while studying at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama 40 years ago; clearly, its impact on him was similarly profound. My previous experience of a live performance of the poem was the actress Fiona Shaw reciting it from memory beneath a single bare lightbulb on stage at the historic Wilton’s Music Hall in the East End on New Year’s Eve, 1998. In my eyes, that gave Dunbar and his crew a lot to live up to.

The readers were Anna Nygh, Orla Charlton, Frank McCusker and Stanley Townsend. Dunbar divided the lines between them, as appropriate to Eliot’s shifting cast of characters. Passages were rendered with German, Irish, American and Cockney accents. I was worried to begin that it might all seem a bit contrived, a bit stagey. That unease evaporated within a few minutes. The polyphony of the reading brought a different kind of life to an already highly polyphonic poem.

Ross’s music was used as an overture and as interludes between the five episodes. The overture, scored for the Guildhall Sessions Orchestra, evoked the European modernist classical music of the inter-war years: bold gestures, hints of dissonance. The first interlude had a ragtime flavour (“that Shakespeherian Rag… so elegant… so intelligent”). For the second, the quintet — Alex Bonney (trumpet), Roth (saxophones), Alex Hawkins (piano), Oli Hayhurst (bass) and Simon Roth (drums) — brilliantly created something that sounded like one of Charles Mingus’s bands paying homage to the pre-war Ellington small groups, or possibly vice versa. The third found the group moving towards free jazz, with Hawkins flailing the keyboard à la Cecil Taylor. The fourth exploited Bonney’s expert manipulation of electronic sound. Did that chronological progression echo something buried within the text? If certainly added a new perspective and a contemporaneity.

Nothing will ever dim the memory of Shaw’s spellbindingly majestic recitation, but Dunbar’s gamble paid off. The drama intensified until, by the time the closing lines of the fifth and final section were reached — “These fragments have I shored against my ruins / Why then Ile fit you / Hieronymo’s mad againe / Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata. / Shantih shantih shantih” — the words and sounds had transformed the climate of a well-warmed hall and I felt a shiver run through me.