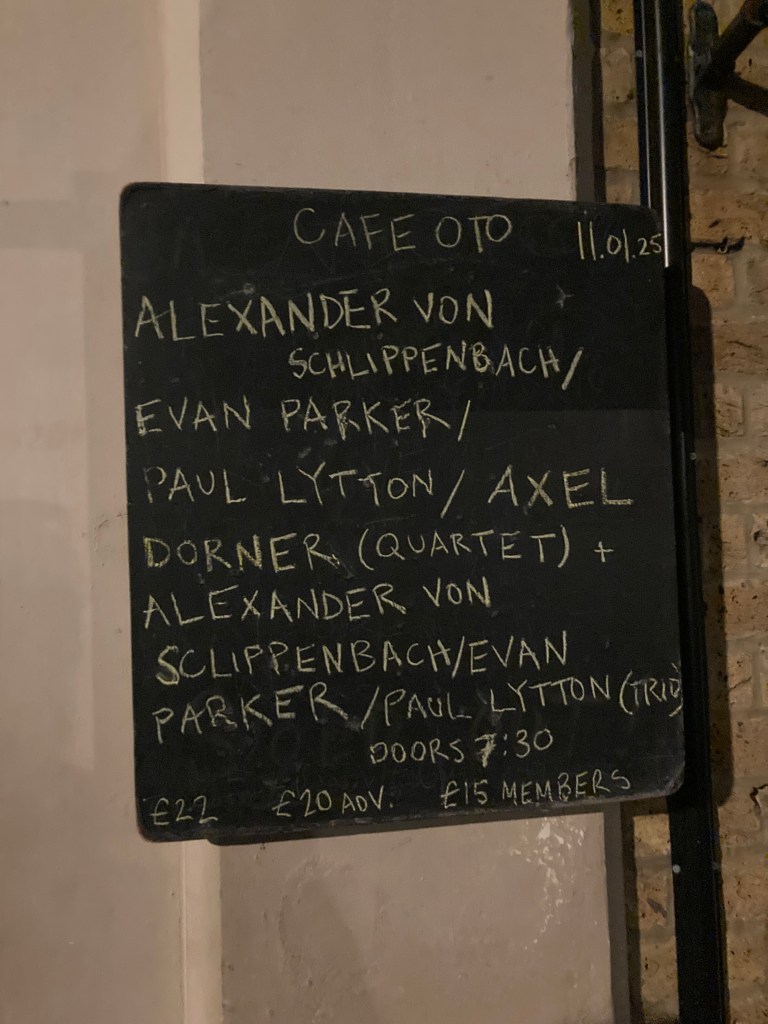

Dave Tomlin 1934-2024

I never met Dave Tomlin, or heard him play live, but the news of his death at the age of 90 rang a bell that echoed back to London in the late 1960s. A Tibetan prayer bell, probably: among other distinctions, Tomlin was the founder of the wonderfully named Giant Sun Trolley, a group who were one of the early attractions, along with Pink Floyd and the Soft Machine, at UFO, the legendary psychedelic club which opened in December 1966 in a Tottenham Court Road basement, where it ran weekly until July 1967.

Originally an army bugler, then a clarinetist with Bob Wallis’s Storyville Jazzmen during the Trad boom, Tomlin switched in the mid-’60s to soprano saxophone, the instrument on which he was featured in the Mike Taylor Quartet, a Coltrane-influenced group led by a strikingly adventurous but troubled British pianist. A recording of a January 1965 gig, with Tony Reeves on bass and Jon Hiseman on drums, emerged under the title Mandala four years ago, supplementing their official release, Pendulum, recorded in October of that year by Denis Preston in his Notting Hill studio.

Taylor’s mental problems, seemingly exacerbated by the prolonged use of LSD, would soon destroy his musical career. According to Ron Rubin, who took over from Reeves as the group’s bassist and played on Pendulum, he was so disturbed that at one point he threatened to kill Tomlin. In January 1969, after a period during which he had been seen busking on the streets with an Arabian clay drum, Taylor’s drowned body was found washed up on an Essex shore, the cause of his death, whether accident or suicide, unexplained.

Tomlin, by contrast, survived the mind-expanding journeys of the time. Glen Sweeney, a jazz drummer when he joined Giant Sun Trolley, met him at the London Free School in 1966 and said in an interview with the archivist Luca Ferrari that he “was known as an ace guy — he’d taken a lot of drugs and dropped out.” Sweeney became Tomlin’s first recruit to Giant Sun Trolley; they were sometimes joined by bassist Roger Bunn (later to become the original Roxy Music guitarist) and a trombonist named Dick Dadem. They split up when Tomlin decided to spend some time in Morocco in 1967, leaving behind no aural evidence of the band’s time together.

Sweeney switched to tablas and formed the Third Ear Band, who became a fixture at underground events. One track of their 1969 debut album for EMI’s Harvest label featured a guest appearance by Tomlin, playing violin on his own composition “Lark Rise”.

Thereafter music seemed to play a smaller role in Tomlin’s life. He was a poet, novelist and memoirist, and between 1976 and 1991 devoted much of his time to the Guild of Transcultural Studies, a community of artists from many disciplines who took informal occupation of London’s unoccupied Cambodian Embassy.

He died three months ago, but I didn’t know about it until one of his sons wrote a short obituary for the Guardian. His death removes another link with the particular Notting Hill microclimate of artistic and social optimism embodied by UFO, the Free School, Blackhill Enterprises, Joe Boyd’s Witchseason and IT. He never became a big name, and probably never wanted to be, but the sound of his soprano saxophone survives on those challenging, sometimes exhilarating Taylor quartet recordings as evidence of a man in his element.

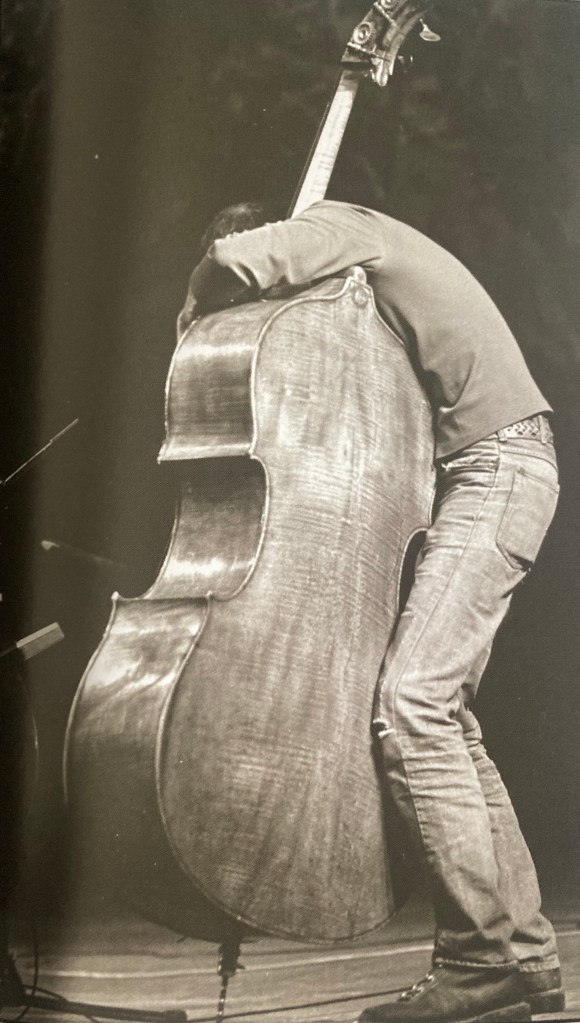

* The Mike Taylor Quartet’s Mandala is a CD on the Jazz in Britain label. Pendulum, originally issued on Columbia, was reissued in 2007 on Sunbeam Records. The Third Ear Band’s three albums were reissued in 2021 in a box set of CDs titled Mosaics by Esoteric/Cherry Red. The photo of Tomlin is taken from Luca Ferrari’s archive: http://www.ghettoraga.blogspot.com