Wherever, whenever and by whomsoever the idea of “world music” was invented, it had no finer exponent, explorer and exemplar than Don Cherry. In a few months’ time it will be 30 years since Cherry died in Malaga of liver cancer, aged 58, leaving a world in which he was, to quote Steve Lake’s happy phrase, “a trumpet-playing lyric poet of the open road, whose very life was a free-flowing improvisation.” I suppose it was fitting that he should have died in Andalucia, a region where many cultural influences met in the Middle Ages to create a foundation of song.

Cherry’s life and work demand a full-scale biography, along the lines of Robin D. G. Kelley’s standard-setting study of Thelonious Monk. In the meantime, it’s worth welcoming Eternal Rhythm: The Don Cherry Tapes and Travelations, a new book consisting mostly of interviews conducted in various locations around the world by the author Graeme Ewens, who met the trumpeter in the 1970s and became his “confidant, travel companion, witness and friend” over the subsequent two decades. They are augmented by Ewens’ memories of their times spent together from Bristol to Bombay, by biographical notes, and by an interesting selection of photos and other visual material.

A useful addition to Blank Forms’ The Organic Music Societies, a Cherry compendium published in 2021, it’s full of worthwhile stuff. Here’s Cherry on playing with Ornette Coleman in the great quartet that changed the direction of jazz: “Ornette would never count a song off: ‘One, two, three, four, go.’ We would feel each other in the silence before playing and then we would play. And the first accent, or the first attack, would determine the tempo and temper of the composition.” And this, which goes to the heart of Cherry’s conception: “One day when Ornette was working on notation, we talked about how you couldn’t notate human feelings. For me, there was always this problem of notated music sounding like notated music. In the older days you never saw black musicians playing with music stands. They learnt it by heart, which is important. For me, when I learn a song with notes it will take time for me to really memorise it, but it’s important to learn it by heart because then you will know it.”

Cherry tells a story about Miles Davis coming to sit in with him and Billy Higgins at the Renaissance in Hollywood and borrowing his pocket trumpet. And then, later in the ’60s, Miles invites Cherry to sit in with his quintet at the Village Vanguard: “So I played something, the changes from ‘I Got Rhythm’ — AABA — and I stopped my solo right before the bridge, which is the B part, and Miles said, ‘You’re the only man I know who stops his solo at the bridge.’ Then later on I heard him doing the same thing. And the next time I saw him he said to me, ‘Hey, Cherry, I play a little like you now,’ which was a big compliment.” Particularly, one might point out, coming from a man who had initially scorned Cherry’s playing.

In an offical note telexed after a concert in Yaoundé in 1981, during a tour of Cameroon sponsored by the US State Department, a consular official writes: “Cherry and companions were real good-will ambassadors: courteous, patient, curious about country, irrepressibly friendly… (the) only problems arose in trying to move them from place to place as they kept striking up conversations in the street.” On page 132 we learn that the pocket trumpet Cherry was playing at the time of his conversation had once belonged to Boris Vian, the writer and critic, and possibly before that to Josephine Baker. On the very next page Cherry mentions an occasion in the 1950s when he and Ornette went to hear a Stockhausen performance at UCLA.

The book doesn’t duck the question of the social conditions under which the music came into being, or the heroin addiction that began for Cherry in the 1950s and continued on and off for the rest of his life. Here, as part of a lengthy disquisition on changes in the heroin trade, is an insight, from the perspective of 1981: “…you always try and keep some morals. There were certain influential white people who were messing with drugs and so I’d be copping for them, and that’s the way I’d survive. But now on the Lower East Side anybody can go and cop. Anybody. Sometimes they’ll ask you to show them your marks before they let you in the building. That world is another kind of world. You cannot compare that world with the people who just smoke grass, because you’re fighting for your life to survive.”

World music hadn’t been invented — or codified as a marketing category — when Cherry moved on from his jazz background. He’d become famous through his association with Coleman, followed by three wonderful albums of his own for Blue Note (Complete Communion, Symphony for the Improvisers and Where Is Brooklyn?), and his work with Albert Ayler, the New York Contemporary Five, the Jazz Composers Orchestra and Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra. His new direction denied nothing of his past but incorporated elements drawn from other cultures, exemplified by his use of bamboo flutes, gamelan and the doussn’ gouni, the six-stringed hunter’s harp from West Africa.

His concert at the Berlin Jazz Festival in 1968, released by MPS under the title Eternal Rhythm, gave a clear indication of where his music was heading. Further evidence came with collaborations with the Turkish drummer Okay Temiz (Orient on BYG and Organic Music Society on Caprice), his duo albums with Ed Blackwell (Mu Pts 1 & 2 on BYG, El Corazón on ECM), his guest appearance on the Swedish drummer-composer composer Bengt Berger’s essay in African ritual modes and rhythms, Bitter Funeral Beer (also ECM), and the three ECM albums by Codona, a trio with the multi-instrumentalists Collin Walcott and Nana Vasconcelos, recorded in 1978-82 (and reissued in 2008 as The Codona Trilogy).

Elsewhere, refusing to be limited by notions of idiom and genre, he turned up on Lou Reed’s The Bells, Rip Rig & Panic’s I Am Cold and a lovely half-hour improvised duet with Terry Riley, bootlegged from a 1975 Riley concert in Cologne. In the early ’80s he toured with Sun Ra’s Arkestra and Ian Dury’s Blockheads.

I want to pass on a pithy little description of Cherry’s playing that I’ve just read in a Substack post celebrating Ornette’s 1972 album Science Fiction by the pianist Ethan Iverson: “Folk music, surrealism, the blues, the avant-garde, deep intelligence, primitive emotion.” That’s good. And, as much as I love his work with Coleman, Albert Ayler and Gato Barbieri, my favourite Cherry albums are probably those that best encapsulate the full range of those qualities, and of his imagination.

They would be Eternal Rhythm, Relativity Suite from 1973 (with the JCOA, never reissued in any form since its its first appearance on vinyl), and the wonderful Modern Art: Stockholm 1977, a concert at the city’s Museum of Modern Art, which appeared on the Mellotronen label in 2014, featuring Cherry and a nine-piece band played marvellously rich acoustic versions of the material from his then-recent album Hear & Now, produced by Narada Michael Walden. It includes a spellbound duet with the Swedish guitarist Georg Wadenius on a graceful Coleman ballad called “Ornettunes” and an ecstatic transition from the gentle groove of “California” (a take on Donald Byrd’s “Cristo Redentor”, with Cherry on piano) to the miniature prayer for transcendence of “Desireless” (first composed as “Isla (The Sapphic Sleep)” for Alexander Jodorowsky’s 1973 film The Holy Mountain and then re-recorded under its new title for Relativity Suite).

It’s easy to imagine that there probably isn’t any music ever played by anyone, anywhere, at any time, from prehistoric hunters on the Eastern Steppe to whatever Kendrick Lamar, Billie Eilish or Nils Frahm are doing next, to which Don Cherry could not have made a worthwhile contribution. And the secret to that must have been his openness.

“I’m self-taught in a way,” he says in the book, “but I’ve always been open to learn, because one lifetime I don’t feel is long enough to really learn music.”

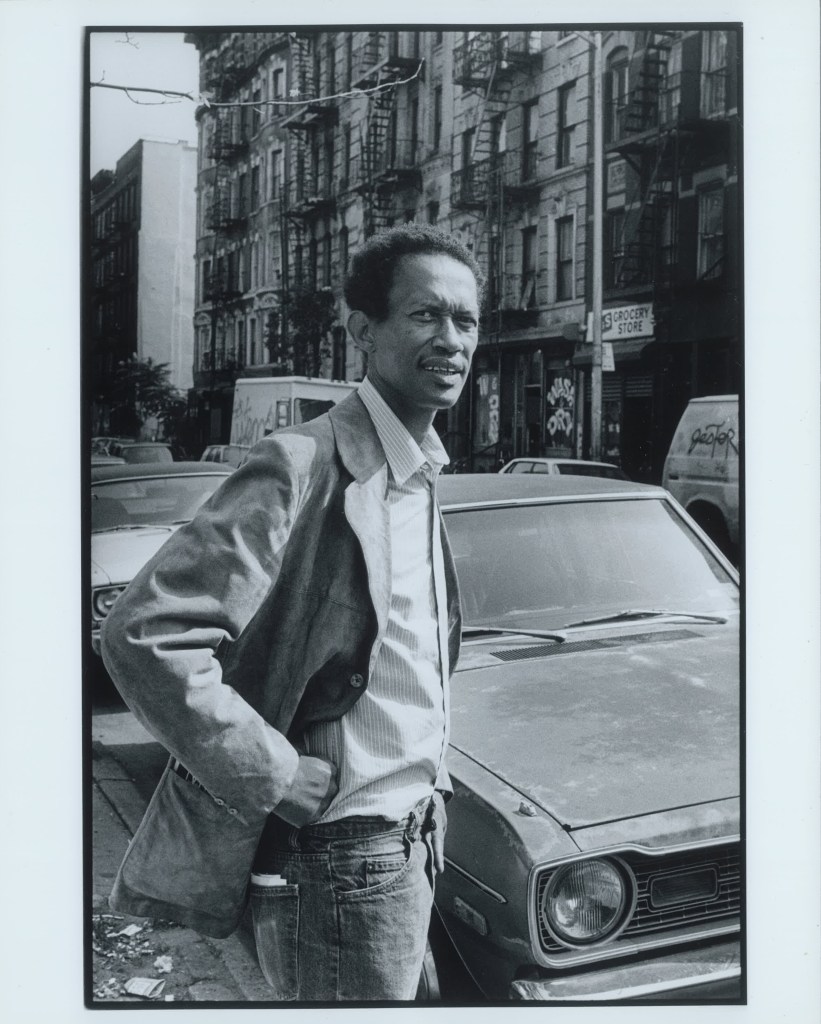

* Graeme Ewens’ Eternal Rhythm: The Don Cherry Tapes and Travelations is published by Buku Press: bukupress@gmail.com. The photograph of Cherry on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in 1988 was taken by Val Wilmer and is used by her kind permission.