Bird at 100

Charlie Parker was born on August 29, 1920. A lot has been written in acknowledgment of his centenary**, about how he changed the way players of all instruments approached the business of playing jazz and about how his improvisations still sound newly minted. I’ve been thinking about those things, too, but also about what he might have left undone.

His final session in a recording studio, on December 10, 1954, three months before his death, saw him record two standards, “Love for Sale” and “I Love Paris”, at Fine Sounds in New York City for Norman Granz’s Verve label. Five takes of one, two takes of the other. Something caused the three-hour session, which would normally have produced five or six masters, to be truncated. Later the best takes of the two tunes formed part of an album called Charlie Parker Plays Cole Porter, the fifth volume of a posthumous series titled The Genius of Charlie Parker. His solos were adequate, but the deployment of the quintet format — alto, piano, guitar, bass and drums — offered him nothing new, no fresh stimulus. The Latin vamp behind the theme statement of “I Love Paris” is tired and lugubrious.

And that, mostly, was the story of his last few years. The increasingly tragic chaos of his personal life and the imperatives that came with it militated not just against artistic rigour and discipline but against any sustained attempt at further artistic development.

In musical terms, what had Bird needed for two or three years before his death was some kind of new challenge. Instead he was corralled by his own supreme mastery of the idiom he had helped invent. The rare attempts to venture beyond the head-solos-head format of small-group bebop, in the dates with strings or the sessions with Gil Evans and the Dave Lambert Singers, saw the compass set for the land of easy listening. Although on the recordings with strings and woodwind — arranged by Jimmy Carroll and Joe Lipman, a pair of journeymen — Parker occasionally produced some celestial playing (and, as it happens, I’m very fond of them), the context was not inherently stimulating.

Yet we know that in the late 1940s Parker had spent time at 14 West 55th Street, Gil Evans’s basement apartment, where George Russell, John Lewis and Gerry Mulligan were among those who met to discuss the future of music and how they might shape it. We know he listened to Bartók and Stravinsky, and that Edgard Varèse had offered to give him lessons in composition. We know he was interested in what Lennie Tristano was up to. He had an omnivorous intellect and was not hidebound by his own genre.

In February 1954 there was a hint, in a very unlikely setting, of how things might have been different. According to Ross Russell in Bird Lives!, it was when Stan Getz went missing after the first date of a 10-city national tour titled the Festival of Modern American Jazz that the Billy Shaw Agency paid Parker a good fee to fly out to San Francisco and take the place of the absent star. Ken Vail’s Bird’s Diary tells a different story, which has Parker playing on every concert from the start of the tour.

The line-up featured Kenton’s 18-piece orchestra — with Stu Williamson among the trumpets, Frank Rosolino on trombone, Charlie Mariano and Bill Perkins in the reed section, Don Bagley on bass and Stan Levey on drums — and a selection of star guests: Erroll Garner (with his trio), Dizzy Gillespie, June Christy, Lee Konitz and Candido Camero. The tour started in Wichita Falls, Texas, and made its way in an anti-clockwise direction around America, its stops including the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville, the Brooklyn Paramount and Toronto’s Massey Hall before ending up at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles.

On February 25 the 18th concert of the tour took place at the Civic Auditorium in Portland, Oregon. Someone made a recording of Bird with the Kenton band, playing “Night and Day”, “My Funny Valentine” and “Cherokee”, all subsequently available on a variety of bootleg LPs and CDs (e.g. The Jazz Factory’s Charlie Parker: Live with the Big Bands, which has better sound than these YouTube clips). These days I find I play them as much as any of Bird’s better known recordings.

From the photograph of him in front of the band, he looks to be in good physical shape. His tone is firm but warm and pliable, his phrasing unquenchably inventive as he sails over the contours of the standards, lifted by the excellent rhythm section. The arrangements are standard big-band stuff, which makes you wonder how Bird would have handled some of the more adventurous material in the Kenton repertoire, by composer/arrangers such as Bill Russo or Bob Graettinger.

It seems to me that if Parker lacked anything in musical terms, it was someone to play Gil Evans to his Miles Davis: someone to envision the kind of setting that would have spurred him on towards new dimensions. Maybe that man could even have been Gil Evans himself, doing for Bird what he did for Miles with the arrangements for Birth of the Cool and Miles Ahead. Their one session together, in 1953, turned out to be the most curious item in his entire discography: mushy choir-and-woodwind arrangements of “In the Still of the Night”, “Old Folks” and “If I Love Again” written to order in a misconceived stab at broadening Bird’s audience (although, once again, they spark some defiantly brilliant alto work, like Basquiat graffiti on a suburban white picket fence).

Imagine if Parker and Evans had been able to work together towards the end of the ’50s, with a good budget and plenty of time to plan and prepare a serious project. Imagine if a healthy Parker, in his mid-forties, had engaged with a coming generation. Imagine a Blue Note date in 1964 under Andrew Hill’s leadership, with Lee Morgan, Richard Davis, Bobby Hutcherson, Grachan Moncur III, Sam Rivers, Tony Williams and Bird tackling Hill’s tunes. Imagine him actually taking a course of study with Varèse, and finding his own compositional voice for a large ensemble, synthesising everything he knew. Imagine Eric Dolphy arranging Bird’s tunes — for Bird.

These are idle thoughts, obviously. He did more than enough. But still… Happy 100th birthday, anyway, Mr Parker.

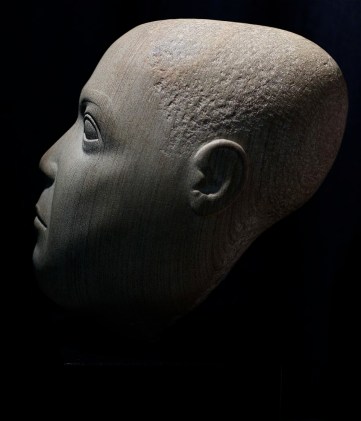

* The stone bust of Charlie Parker was made by the sculptor Julie Macdonald, a friend with whom Bird stayed in Los Angeles at the end of the Festival of Modern American Jazz tour. The photograph was taken by its present owner, William Dickson, and is used by his permission. I told the story of the sculpture here in the Guardian a few years ago. The photo of Parker as an infant is from To Bird with Love by Francis Paudras and Chan Parker, published by Editions Wislov in 1981.

** More stuff on Bird’s centenary: Ethan Iverson’s Do the Math, a New York Times special, and the start of a multi-part series on Ted Gioia’s Jazz Wax blog.

When the 10 CD “Complete Charlie Parker on Verve” was released in 1990 and there were three heretofore unreleased complete takes of “In The Still of the Night”, it was like discovering a new way to breath. As Bird says at the end of one take, “Let’s do another one, right quick.” Three new takes of “Old Folks” were just icing on the cake. My ears just sort of eliminate Evans choir and woodwinds and zero in on Tony Aless, Charles Mingus, Max Roach, and Bird in flight. Lovely piece. Thank you.

Thanks Richard, lovely writing…will be listening to plenty of Bird on his centenary.

Interesting to hear your musings on what could have been…his early passing was such a tragedy to the music world.

A very thoughtful piece which I am sure will provoke scholarly responses.

Meanwhile WKCR, the radio station of Columbia University in New York, is celebrating “The Charlie Parker Centennial from August 29th – September 2” celebrating 100 years of Bird.

It is easy to download the app and listen on line, I’m listening now. Phil Schaap’s “Birdflight” is a regular feature. He is a devoted scholar of the whole life story of CP with an astonishing grasp of the detail.

It would be very interesting to hear his take on your view of the end period of Charlie Parker’s music.

Wall-to-wall Bird perfect! Thanks for the tip Evan

Basquiat graffiti on a suburban white picket fence).—-Oh yea ..

Your piece has solved a puzzle for me going back some years.

There’s a reproduction on the back of an LP called “Jazz in the Movies” on Milan A370 of a portrait of a naked Charlie Parker, Bird 1952, by Julie McDonald which is presumably one of the sketches she made of him at that time. I haven’t seen this reproduced anywhere else, and until I read your article I hadn’t made the connection with Reisner’s book.

There’s no indication on the LP where the illustration comes from (I see the LP copyright is held by Stash but this may refer only to the recordings on the LP).

If you’re not familiar with this please let me know if you’d like me to send you a scan.

Hi Peter, for those of us interested, would be nice to see a scan of that cover. One of my pals has two drawings by Julie of Bird. Maybe yours is one of them.

It’s maybe wishful thinking to imagine Bird working with the Young Lions of Blue Note and studying with Varèse but it is a beautiful thought.

What actually would have happened would probably have been endless touring with JATP, many reunions with Diz and other survivors of the bop era.

Collaborations with Gil could certainly have been a possibility but equally the Bossa Nova album and the uncomfortable alliance with the burgeoning rock scene may have happened.

Who knows, but I’ll mark the anniversary by listening to the astounding version of “The Street Beat” from Birdland where Bird,Bud and Fats are flying

Yes Richard we can imagine all that and the music created ….just imagine

But thanks

Thank you for this great piece with your lovely musings about what might have been. Among other things, you bring out the fact that CP had very catholic tastes. One example I recall my late father (guitarist Pete Chiver) telling me about relates to Bird’s 1949 Paris visit. Dad, together with a number of British fellow musicians including Messrs Dankworth and Scott, went to Paris to see him and got to meet Bird–obviously a big thrill. My father was a friend of Django Reinhardt–who he had got to know and played with during Django’s wartime visits to London–and he tried to persuade Bird to accompany him to go and see Django who was playing at a different venue in Paris. Bird politely declined saying he wasn’t that familiar with Django’s playing at that time and that in any case, he had just recently been to a performance by another guitarist who he thought was wonderful and that he couldn’t conceive of anyone being better. Needless to say, dad asked him who this guitarist was. The answer was Segovia.

Great to hear these tracks with Parker joining the Stan Kenton Band. They certainly stimulate thoughts about what could have been with Parker had he lived. I also enjoy Parker’s playing on One Night in Washington (February 1953) when he joined a big band apparently unannounced, without any music and with his plastic saxophone to play their repertoire of well arranged standards such as Thou Swell and These Foolish Things. Parker plays with great energy and interacts nicely with the band.

The problems of Bird’s last few years can be summarized by one solitary word

DRUGS !

Which succinctly and utterly destroyed his ability to be creative or as Richard bemoans … seek new challenges

Which is to say Bird was the agent of his own demise and destruction … which is sourly evidenced by the lack of creativity and spark that is found in his later recordings

So rather than mystify and romanticize a self inflicted tragedy .

Let Bird’s 100th be a reminder/warning to all … as Miles told me …. ” Leave that *&@#ing $4!t alone “

A well-voiced set of speculations. I too have often wondered what direction Bird’s music might have taken, and as you intimate, the journey may have rather stayed its course.

Bird’s oeuvre may have entrapped by its very percussive fierceness; heard today, it sounds almost implacably stylized, perhaps in turn ultimately inescapable from itself. A search for Bird’s Gil Evans then, would likely shamble into a dead end, because Bird’s musical DNA cannot be mapped fitly onto Miles Davis’ persona. The latter’s approach – far more elliptical, literally more spacious, tinted with mystery and ground far more lightly into the rhythmic warp – was of the sort that could lift itself above its trammels and move on. Not so with Bird, I would suggest.

Thus it is difficult to imagine Bird resonating to the modal shift that soon overtook the music. Can one imagine Bird playing So What? I have my doubts. Unlike John Coltrane, whose conception always inclined toward stasis, Bird gave us no indication he might have headed that way. But who knows?

Many good thoughts in this piece, though I think there are examples in his work even near the end when he played splendidly. One would be the quartet session for Norman Granz that took place on July 30, 1953, with Al Haig, Percy Heath and Max Roach which produced, among other delicacies, a stunning version of “Confirmation.” I do wonder if drugs had not been part of his life where he would have gone. Apparently, there is a lot of discussion about his interest in Stravinsky on this forum, found on Loren Schoenberg’s Facebook page, if this link does not work:

Cheers, keep wailing.

Listening to the celebration of Bird’s music on WKCR is an absolute delight, just to to be able to turn the radio on at any time and be guaranteed to hear his genius.

Phil Schaap suggests that the death of Parker’s daughter Pree had, understandably, a devastating effect on his life and quite possibly his playing. This occurred shortly after the Kenton recordings on March 5th, his playing on the first Porter session later that month whilst not of the highest order is still on a different plateau from any contemporary altoists.

Also the choice of “My Heart belongs to Daddy” a trite song was perhaps not the wisest choice, which even Bird struggles with.

Anyone wishing to access Schaap’s massive archive of recordings can find them here, in particular the many Bird Flight programmes

http://www.philschaapjazz.com/index.php?l=page_view&p=radio