Lambert & Stamp

It amazes me that so many documentary makers fail to heed the principal lesson of Asif Kapadia’s Senna, which is that any relevant archive footage, however scrappy, is more interesting than a talking head. It’s a pity that James D. Cooper didn’t learn it before he started putting together Lambert & Stamp, his film about the two men who managed the Who from their first success in 1964 until the relationship broke down in acrimony 10 years later.

It amazes me that so many documentary makers fail to heed the principal lesson of Asif Kapadia’s Senna, which is that any relevant archive footage, however scrappy, is more interesting than a talking head. It’s a pity that James D. Cooper didn’t learn it before he started putting together Lambert & Stamp, his film about the two men who managed the Who from their first success in 1964 until the relationship broke down in acrimony 10 years later.

A compelling subject is enough to carry the first half of the film. After that the viewer tires of extended close-ups of Pete Townshend, Chris Stamp and Roger Daltrey sitting in hotel rooms or studios, even when they’re saying interesting things. The archive clips are chopped up and edited fast on the eye, to borrow Bob Dylan’s phrase. Too fast, in fact. The eye wants to rest on them, to be given time to absorb the details. A technique wholly suited to the titles of Ready Steady Go! is not appropriate to this very different project. The exception is a wonderful piece of footage of Stamp and Kit Lambert encountering Jimi Hendrix and Chas Chandler in a London club, possibly the Ad Lib or the Bag O’Nails; we do get to look at that properly, thank goodness.

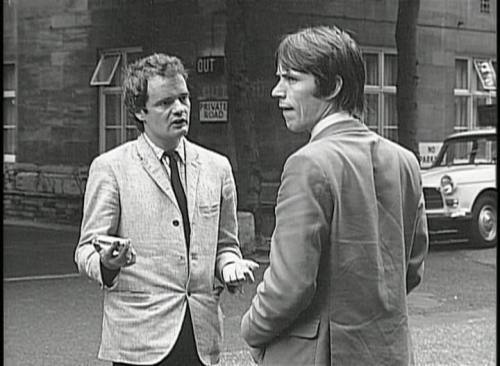

It’s a story that certainly deserved to be told. Stamp — born in London’s docklands, the son of a tugboat captain — brother of Terence, the male face of ’60s London — almost as good looking but sharp and tough, with more front than Harrods. Lambert — Lancing, Oxford, the Army — the gay son of a celebrated English composer — explaining mod culture to foreign TV interviewers in fluent French and German — empathising immediately with Townshend’s latent talent and Keith Moon’s very unlatent lunacy.

A pretty bruiser and a bruised prettiness: it was a potent combination. “I fell in love with both of them immediately,” Townshend recalls. It’s easy to see how he and, to varying degrees, the other members of the Who were jolted into self-actualisation by the vision and audacity of a pair of energetic wide boys whose real ambition was to get into the film business and who initially saw the music as a vehicle for their ambition.

The viewer does not come away with the impression that the whole truth about the break-up in 1974 has been told, and a few other salient features of the story have gone missing. One is any acknowledgment of Peter Meaden, their first manager when they were still the High Numbers: an authentic mod who helped establish their direction. Another is Shel Talmy, the producer of their first three (and greatest) singles, given only a passing and mildly derogatory mention, without being named.

Lambert died in 1981, aged 45, worn out by his destructive appetites, although the immediate cause of death was a cerebral haemorrhage following a domestic fall. Stamp had conquered his own addictions long before his death in 2012 at the age of 70, having spent many years as a therapist and counsellor. His interviews with the director are used extensively but, lacking the matching testimony of his former partner, his wry eloquence inevitably seems to unbalance the narrative.

At 120 minutes, the film eventually feels bloated. If the first hour passes like a series of three-minute singles, the second is a bit of a rock opera, the occasional interesting fragment separated by long stretches of filler. But, of course, anybody interested in the era should see it.

The bulk of the early footage comes from a Telepool German TV Documentary called Die Jungen Nacht Wandler – The Young Night Walker, which followed four folks across a weekend out in London in 1967 (or was it 1966?) The three main characters were Stamp, Lambert, Terence Donovan the photographer and a model whom Stamp was seeing a the time. Trinifold – the Who’s management – demanded this footage back when I 1st located this in Switzerland in 1995 when working as an Archive Consultant for Channel 4 TV. The German’s capitulated and this phenomenal footage makes up much of the film you see here. Henry Scott-Irvine

I saw the film yesterday and thought it was amazing. The fast editing and whatever trickery was worked with the soundtrack – adding echo, possibly mixing in surround sound on some of the early 70s live tracks (from the why-don’t-they-just-release-it San Francisco 1971 concert) – gave tremendous energy and edge to the first half. I’m not generally a fan of fast-cut documentaries but it seemed appropriate to the subject matter, I thought. Maybe I’ll think differently when I see it on a small screen.

And you’re probably right about the second half – perhaps more veiled and, bereft of much moving image to play with, it had a different feel and pace to the first.

Either way, a terrific sense of the era and what was possible.

I had the pleasure of seeing the film yesterday. Perhaps like the Who’s career the first half is an adrenaline rush as our two heroes successfully navigate the band’s rise against all the odds, before the film gets bogged down in concept albums and as Chris Stamp puts it ‘hippy dippy stuff’. I thought Chris Stamp was riveting on screen-the grown up artful dodger?

My other thought was ‘could this ever happen again?’ in a world of manufactured bands,studio gloss, and curation before the history, will we ever see their like again?

I broadly agree with your thoughts. The opening twenty minutes were stunning to me, fast cuts adding a mad tempo to the mad times. Yet it does slow down in the second half with too much of a surprisingly inarticulate (to me, at least) Chris Stamp at times and had it been made for a major company I suspect older, wiser heads who may have known nothing about rock and roll but did know cinema would have said “cut at least fifteen minutes of the last seventy minutes” to make it move forward more.

And it is true we cannot be getting the entire story of their split. As for Meaden and Talmy getting nary a nod that is unfortunate but some people carry their grudges for years easier than they do their groceries for a few minutes. Nonetheless a must-see film and I thank your first correspondent above for the info about The Young Night Walker.

I have to agree with what you say Richard. I saw this film myself and reviewed it at some length on my blog. It could have been trimmed by 30 minutes and the reliance on recent interviews with Chris Stamp created an imbalance. I still enjoyed it though, but I’d seen a lot of the archive material before. Surely Kit L was the only multilingual manager in the business.

Good one.

Kapadia did a deal with Ecclestone and the Senna family that cost millions. It was based on a hunch that there was film in the FoM vault that hadn’t been seen that would throw light on Senna’s mindset. The more he found, the less he needed the interviews he did, until by the end of the edit he didn’t need them at all except in voice-over. Getting hold of global rights in perpetuity in all media known or unknown on a subject like rock music is the necessary start point if a film is going to get the exposure it will need. Relatively, talking heads cost almost nothing. So it’s not an artistic judgement, its a budget judgement. As content becomes king, archive rights are going to continue to skyrocket. So most TV and movie people agree that all-archive series like The World at War, or The Great War are now impossible to make, financially.

Thanks, Patrick. It’s most interesting — if depressing — to hear that from one who knows the field so well.