Wardell’s last stand

In the days when I covered the big fights in Las Vegas, I always tried to persuade the newspaper to let me have a rental car. As budgets tightened, that became increasingly difficult. Why would you need to spend the department’s money when the only essential travel expenditure, apart from the plane ticket, was the price of a taxi to and from McCarran airport? If you were staying at, say, the MGM Grand, and that’s where the fight was being held, then it was a hard argument to make. But the key to getting the best out of Vegas, it always seemed to me, involved possessing the means to get away from it.

In the days when I covered the big fights in Las Vegas, I always tried to persuade the newspaper to let me have a rental car. As budgets tightened, that became increasingly difficult. Why would you need to spend the department’s money when the only essential travel expenditure, apart from the plane ticket, was the price of a taxi to and from McCarran airport? If you were staying at, say, the MGM Grand, and that’s where the fight was being held, then it was a hard argument to make. But the key to getting the best out of Vegas, it always seemed to me, involved possessing the means to get away from it.

Not that I actually disliked the place. Disapproved of it, maybe, but I was always fascinated by the dark history of how a desert truck stop became the fastest growing city in the US. Just a few weeks ago, for instance, I found myself wishing I’d gone to the Mayweather fight, simply to get a Vegas fix. But had I been there, I’d have been itching to get into a car and head as far away from the Strip as newspaper deadlines allowed — perhaps to the Red Rock Canyon state park, or more probably to the Mexican swap-meet on the north-eastern edge of town, out towards Nellis Air Force Base, a giant open-air weekend bazaar where you can buy anything from a cassette of norteño music to a tyre for your earthmover.

I was always a little sad that Vegas’s eye for future profit had led it to blow up the past behind it. I was there just in time to see the old Sands, for example, still in operation; on my next visit, the former Rat Pack playground was just another vacant lot, waiting for redevelopment. That sensational example of ’50s modern resort architecture — slogan: “A Place in the Sun” — was torn down in 1996. It seemed very short-sighted. If they’d been smarter, the city fathers would have preserved one of those old hotels as a living memorial.

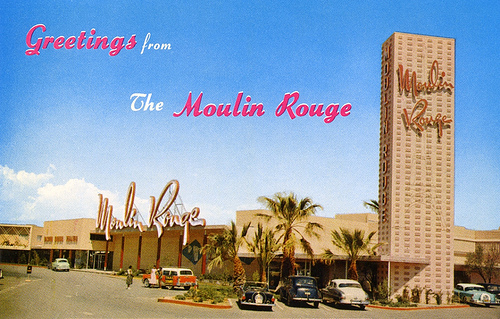

Such thoughts were on my mind when I got in the car on a hot afternoon one day about 10 years ago and headed for Vegas’s Westside, the remote black section of town. I was looking for whatever was left of the Moulin Rouge, opened in May 1955 as the town’s only non-segregated casino hotel. This was a time when black entertainers performing on the Strip were barred from staying in the establishments that employed them; famously, after Sammy Davis Jr went for a swim in the pool at the New Frontier, the management had it drained. Not surprisingly, the Moulin Rouge was a great success. Some of the great stars of the era played there, including Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday and Dinah Washington, and among those who headed across town to enjoy the shows and the relaxed ambiance were Frank Sinatra, Tallulah Bankhead, Cary Grant, Judy Garland, Bob Hope, Dorothy Lamour and Gregory Peck. They were greeted by the former world heavyweight champion Joe Louis, the Brown Bomber, who had been given a small ownership stake by the project’s white backers.

After six months, however, the place was suddenly closed, overnight, without warning or explanation. The croupiers, the cocktail waitresses and the dancers were paid off. The belief has always been that the Mob didn’t like the idea of customers being drawn away from their places on the Strip, and took appropriate action.

I’d heard that, half a century later, it was still standing, so I drove around the Westside, where some of the streets were still unpaved and the visitor felt a world away from the neat and ever proliferating suburban estates housing most of Vegas’s well heeled incomers. And when I found my way to 900 West Bonanza Road, there it was: the low buildings and its high landmark tower still intact, and most of all the giant neon sign, 60ft high and a classic of its type.

I drove in through a gate in the wire fence, parked the car and approached a group of workmen. They told me that it had been used as welfare apartments for some years, and that it had gone through a period when it was notorious as a kind of crack supermarket. Now, following a bad fire a couple of years earlier, it was almost deserted. The workmen told me that plans were under way for it to be refurbished and reopened, more or less as per its original incarnation.

A few calls confirmed that such optimistic plans did indeed exist. The building had already been listed on the National Register of Historic Places, but that turned out to be a meaningless gesture. Further fires, a failed foreclosure sale and pressure from vested interests persuaded the local authorities to issue a demolition permit, and the most significant parts of the property were torn down in 2010. The giant sign, designed by Betty Willis, a local woman, was removed to the city’s Neon Museum, where 150 such relics are preserved.

All this came to mind the other day when an album called Way Out Wardell came through the post. This is a CD reissue, on Ace Records’ Boplicity imprint, of an LP — originally on the Modern label — made up of two recordings from two 1947 concerts, at Pasadena Civic Auditorium and the Shrine in Los Angeles, both featuring the tenor saxophonist Wardell Gray with a couple of all-star groups including Erroll Garner on piano, Howard McGhee on trumpet and Benny Carter on alto saxophone, under the banner of Gene Norman’s “Just Jazz” concert series. It was Carter who, eight years later, was hired as the musical director of the Moulin Rouge, and his big band was the main attraction during the gala launch week.

On the opening night, Wardell Gray was present and correct in the reed section. At 34, born in Oklahoma City but raised in Detroit, and a Los Angeles resident since 1946, he was a player with a substantial reputation. He had made his recording debut in 1944 with Billy Eckstine, appeared on Charlie Parker’s “Relaxin’ at Camarillo” date, and become a favourite sideman of Benny Goodman and Count Basie. The two-part 78 of “The Chase”, his duel with his friend and fellow tenorist Dexter Gordon, a recreation of their marathon battles in the clubs of Central Avenue, had been a hit in 1947. His career stalled a little in the early ’50s, perhaps thanks in part to the acquisition of a heroin habit, but he was still playing clubs and making the occasional record date when he took Carter’s call and headed for Vegas.

On the Moulin Rouge’s second night, however, he didn’t turn up. The band waited, knowing that his habit had rendered him not entirely reliable, but eventually went ahead without him. The next day his body was found in the desert on the outskirts of town. It was assumed that he had died of an overdose, either accidental or administered as a “hot shot” by a dealer to whom he owed money, but the police investigation was cursory at best and no one was ever able to come up with an explanation for marks of blows to his head or exactly how the body might have found its way to its last resting place.

The story was explored at some length back in 1995 in Death of a Tenor Man, one of a series of atmospheric and entertaining crime novels by the American musician and author Bill Moody, whose fictional protagonist is a jazz pianist and amateur detective called Evan Horne. Moody grew up in Southern California but lived for some years in Vegas, where he taught English at the university as well as playing the drums with bands on the Strip, and the local colour is authentic.

So many jazz musicians perished as a direct or indirect result of the heroin plague of the 1950s. Gray’s demise has always seemed one of the most poignant, particularly since the town in which he died was built largely on the laundered profits of a narcotics trade pioneered by the likes of Meyer Lansky and Bugsy Siegel, the principal founders of modern Las Vegas. Which is just one of the reasons why I find it hard to warm to the place.

As with Chet Baker, it’s impossible now to assemble the individual components of Gray’s tragedy into a definitive account. So we’ll never know the truth. But Way Out Wardell finds him at full strength, playing for enthusiastic audiences. Maybe this is how he sounded — confident and full of ideas — on that opening night at the Moulin Rouge, before the curtain came down.

An excellent evocation, Richard. Thanks for including the address – a swift check of Google Maps shows a vacant lot. Wikipedia also has a good piece, written by someone who is clearly angry at the way the building was treated.

Richard

I know what you mean about Vegas but it is nonetheless fascinating in many ways. In 1978 my wife and I were on an extended trip around the USA and arrived in Vegas on 24th June just in time to see the live telecast in the Aladdin Theatre of the World Cup Final between Argentina and Holland which they won 3-1 in extra time. We were amongst the few Europeans in the audience of cheering Hispanics but we had a great time. We stayed in the now defunct Dunes Hotel and won enough money on the slots to pay for our two nights and meals! We drove up and down the strip and visited a chaotic Circus Circus as well as Caesars Place and other casinos and had an all you can eat breakfast for 97c! Thanks form a great piece.

Las Vegas, a place I’ve never been, but yet another wonderfully evocative piece of writing, Richard.

Long may you run.

Nearest I got to Vegas was getting on the press list for Virgin’s inaugural flight, but I was ill and couldn’t go. This is nearly as good as a visit though – just wonderful writing.

As a fellow crime-writer (fellow of him, that is) good to read your positive mention of Bill Moody’s book on Wardell Gray. For my money, his best Evan Horne book is ‘Looking for Chet Baker’- and not just because he quotes my Chet Baker poem therein!