And on drums, Jimi Hendrix…

Stevie Wonder can play the drums (listen to “Creepin'”). So can Paul McCartney, after a fashion (“Maybe I’m Amazed”). But I didn’t know that Jimi Hendrix knew how to use a pair of sticks, too.

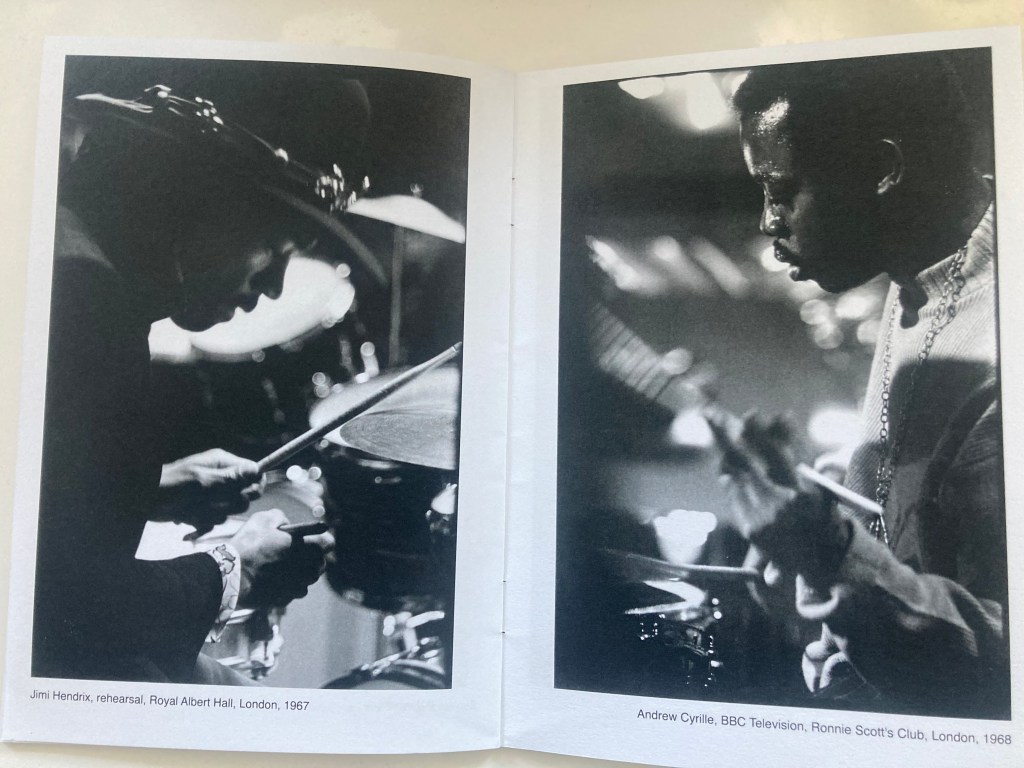

The proof is in American Drummers 1959-88, Val Wilmer’s new book of 36 photographs of drummers she has observed on and off the stage — and in the case of Hendrix (the only one of her subjects better known for something else), during a sound-check before his show with the Experience at the Royal Albert Hall in London on November 14, 1967.

It’s tempting to assume that Hendrix was just messing around when he sat behind Mitch Mitchell’s kit and picked up a pair of his sticks. But the photo is the evidence that he knew what he was doing. He was left-handed, of course. And he’s holding his right-hand stick in the way that a right-handed drummer would hold his left stick, were he using what is known as the orthodox grip, in which the stick rests in the cradle formed by the clefts between the thumb and forefinger and the second and third fingers.

You can see it on the opposite page in the photo of Andrew Cyrille, a great jazz drummer who has played with Cecil Taylor and many others. Cyrille is a high accomplished technician and most of the time he uses the orthodox grip. The alternative is the matched grip, in which both hands hold the sticks in the same way, as if (to make a crude analogy) they were saucepan handles. Charlie Watts used the orthodox style, Ringo Starr the matched grip.

Drummers sometimes switch from orthodox to matched when they want a particular kind of power — playing the Bo Diddley beat, for instance. And it’s the way most people who aren’t drummers hold the sticks if they’re given the chance to hit something.

But Hendrix is unmistakably using the orthodox grip, which set me thinking. Did he learn it from someone who played drums in one of the bands he’d been in, backing the Isley Brothers and others? Or from Mitch Mitchell, whose early leaning was towards jazz? That seems a bit unlikely to me. You don’t generally learn the orthodox grip unless there’s a very good reason.

So it sent me back to his days in the US Army, drafted into the 101st Airborne Division (the “Screaming Eagles”) in 1961 as an alternative to a jail sentence for joyriding in stolen cars when he was still in his teens. He hated it and lasted barely a year, given a discharge after breaking his ankle in a parachute jump. The only reference I can find to musical involvement during that year was when he asked his father in a letter from Fort Campbell on the Kentucky-Tennessee border to send him the guitar he’d left at a girlfriend’s house in Seattle.

But what if he’d been given the chance to join a marching band, and received basic tuition in playing a shoulder-slung snare drum? That would require a mastery of the orthodox grip, because that’s what it was invented for. And although it might seem at first to be awkward and unnatural, once you learn it, it never goes away.

Val’s photos are full of all the qualities that make her work so special (and which I wrote about when she had an exhibition last year). Yes, there are pictures here of musicians playing on stage — Philly Joe Jones, Max Roach, Kenny Clarke, Tony Williams, Billy Higgins, Elvin Jones, Milford Graves — but also in other, different moments: Sunny Murray reading the paper, Marquis Foster getting his drums out of the trunk of his car, Denis Charles loosening up with a practice pad.

And there are other stories, hidden and half-hidden. A well known New Orleans drummer called Freddie Kohlman is pictured playing a snare drum with the Onward Brass Band at a funeral in 1972. Val told me this week that Kohlman — who died in 1990, aged 75 — had told her how the fledgling Motown label had paid for him, and one or two others, to travel to Detroit to teach the company’s studio musicians how to play the New Orleans rhythms that were the basis of R&B and rock and roll.

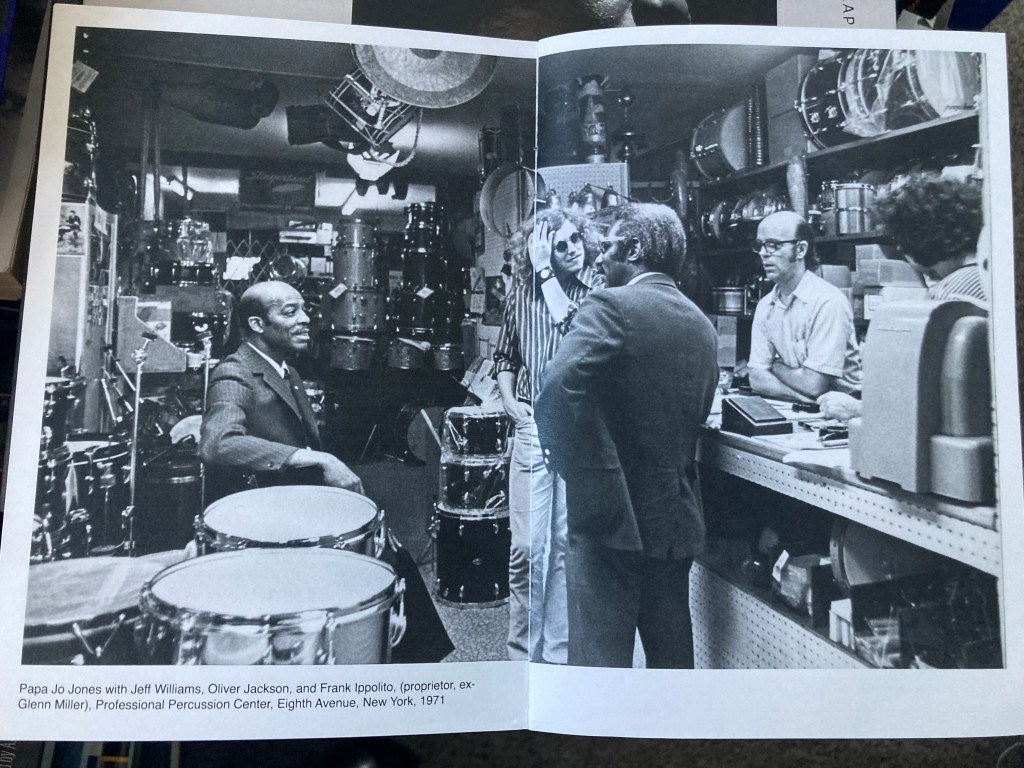

Musicians trusted Val, so she could capture them in less formal settings. Below you can see a scene in the Professional Percussion Center on New York’s Eighth Avenue one day in 1971, with the proprietor, Frank Ippolito (who played with Glenn Miller’s Army Air Force Band during WW2), behind the counter, chatting to a trio of customers.

On the left is “Papa” Jo Jones, whose work with Count Basie in the 1930s survives somewhere within the work of every jazz drummer today. In the middle is Jeff Williams, a 21-year-old Berklee graduate from Ohio about to embark on a professional career with the bands of Lee Konitz and Stan Getz (and who has been based for many years in the UK, teaching at the Royal Academy of Music and the Birmingham Conservatoire). On the right is Oliver Jackson, one of Papa Jo’s acolytes, an underrated player with a sense of swing to match that of Roach, Higgins or Frank Butler, as you can hear if you listen to King Curtis’s “Da Duh Dah”.

Just a bunch of guys shooting the breeze in a drum shop one day half a century ago. And, like a lot of Val’s photos, it invites us to share the privileged access that produced this lovely little book.

* Val Wilmer’s American Drummers 1959-1988 is published by Café Royal Books (caferoyalbooks.com), price £6.70.