Tour de force

As we queued in the Dalston drizzle outside Cafe Oto for last night’s sold-out show by the Tyshawn Sorey Trio, I don’t suppose many of us realised quite the extent to which we were about to enter a better world.

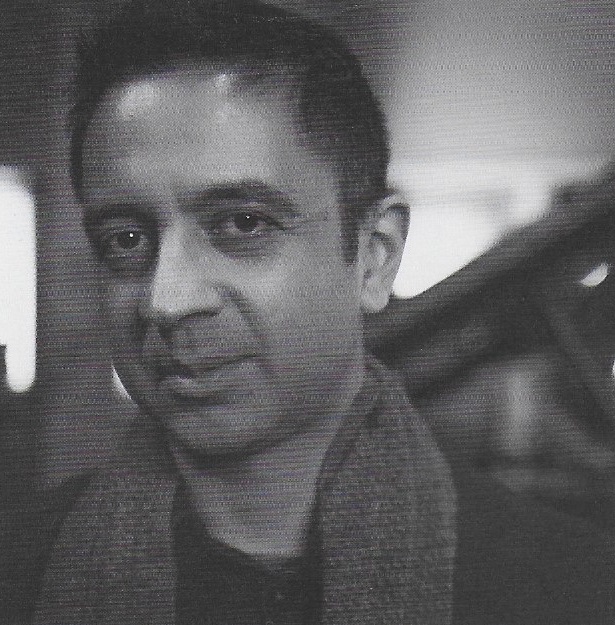

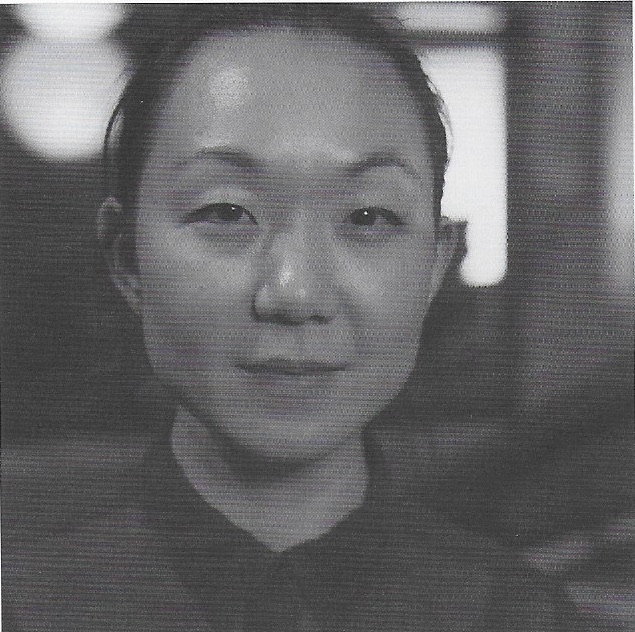

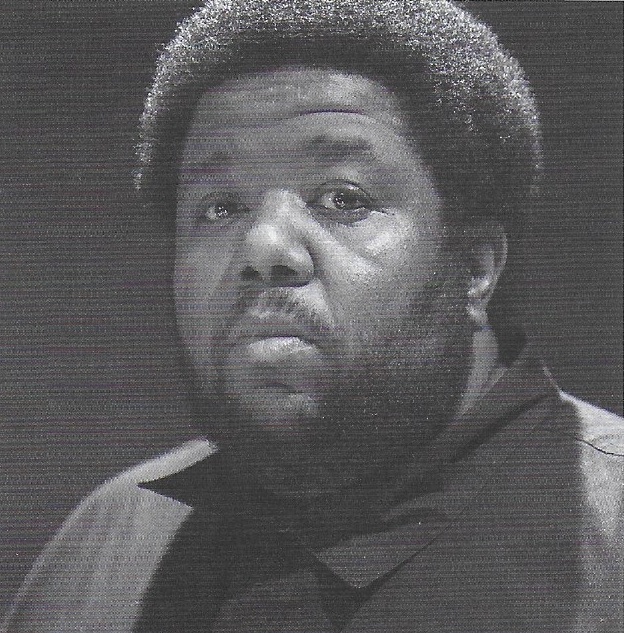

Outside: the return of territorial conquest as a mode of historical change, the revived persecution of minorities, the increasing contrast between private affluence and public squalor, the plight of bankrupt councils trying not to close libraries and other basic services, the destruction of humanities courses in universities, the malign manipulation of such digital-era innovations as AI and cryptocurrency, the exaltation of spite, revenge and mistrust in public life, and the general deprecation of the public good. Inside: playing non-stop, without a break, for two and a quarter hours, Sorey and his colleagues, the bassist Harish Raghavan and the pianist Aaron Diehl, reminding us of what human beings can do, at their very best.

There was too much to describe. This is a group that thinks in long durations, in slow development, in whispers as well as roars. Its three albums (the first two of which had Matt Brewer on bass) fully demonstrated those priorities. In person, however, the effect is more than redoubled, thanks to the brilliance with which they manage the flow and its sometimes radical transitions through nothing more than eye-contact cues, twice managing gradual and beautifully calibrated accelerations that transported the crowd as well as the musicians.

Each player is a virtuoso, a product of intense learning and dedication as well as innate talent. But the machine they build, as with any great group, is superior to the sum of its constituent parts. There were elements of blues and gospel in some of the vast, surging climaxes that drew shouts from the audience, and of ballads and different shades of blues in the passages that flirted with silence. Sorey’s rattling Latin rhythms bounced off the walls; his gossamer shuffle barely disturbed the air. Diehl’s dizzyingly fast upper-register filigree phrases spun with a centripetal force. Raghavan’s assertive agility was balanced by deep thoughtfulness.

Their repertoire avoids original material in favour of extended explorations and dissections of generally lesser known pieces by significant jazz composers: Ahmad Jamal, Duke Ellington, Muhal Richard Abrams, Wayne Shorter, Horace Silver, Brad Mehldau, McCoy Tyner, Harold Mabern. Since the chosen themes are not the obvious ones, and are not identified in performance, the audience listens with fresh ears, unaffected by the comfort of familiarity, open to everything they do.

“See you on the other side,” Sorey had said before the start of the journey. After an hour or so, during a quiet passage, he asked: “Y’all still with us?” Not only were we still with them, both then and at the reluctant end of the performance, but many of us were probably still with them on the journey home and on the morning after, and will be with them for some time to come. An unforgettable night.

* The Tyshawn Sorey Trio’s three albums — Mesmerism, Continuing and The Susceptible Now — are on Pi Recordings, available at tyshawn-sorey@bandcamp.com

** In the original version of this I had a moment of brain fade and wrote “public affluence and private squalor”. Now corrected.