Passion / Compassion

Back in the early 1970s, Santana were my favourite live band. I saw the original line-up — more or less as heard at Woodstock — at the Albert Hall in 1970 and twice the following year, at Hammersmith Odeon and the Olympia in Paris. They were thrilling, and surrounded by a sense of excitement; before the show in Paris, I remember Mick Jagger and Bianca Pérez-Mora Macias sweeping through the backstage bar, a week ahead of their wedding.

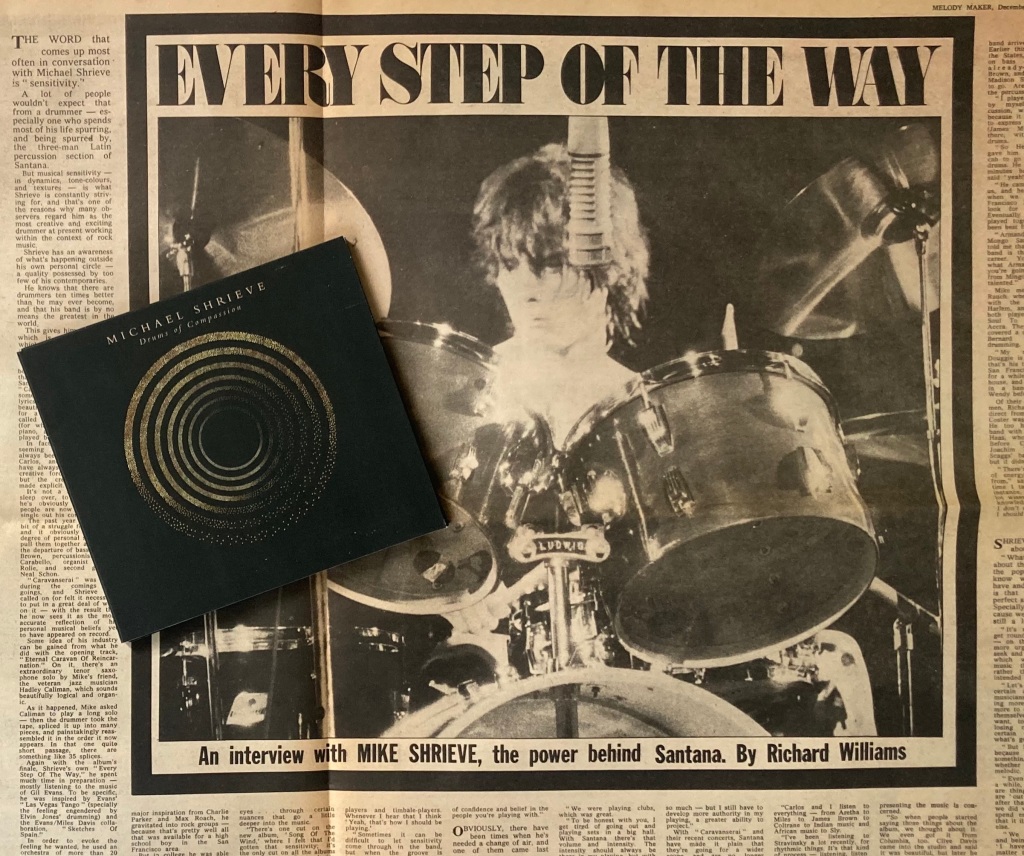

Then the music changed, and they became even better. Carlos Santana and Michael Shrieve had been listening to John Coltrane and Elvin Jones and to Miles Davis’s Sketches of Spain and Bitches Brew. Santana’s fourth album, Caravanserai, brimmed over with the effect of those influences, starting with an unaccompanied solo by the saxophonist Hadley Caliman and culminating in the ecstatic nine-minute “Every Step of the Way”, a Shrieve composition. Clive Davis, the president of their record company, called it “career suicide”. At the Wembley Empire Pool in November 1972, just after the album’s release, an expanded line-up rose to a different level, musically and spiritually.

After Wembley they went off to play some concerts in Europe before returning towards the end of the month for dates in Manchester, Newcastle and Bournemouth. On Thursday, November 23 they had a day off in London, and, being American, arranged a small Thanksgiving Day dinner in the private room of a restaurant on Davies Street in Mayfair. I’d raved about Caravanserai in the Melody Maker, so they were kind enough to invite me to join them for what turned out to be a very pleasant evening.

While they were in London I interviewed Shrieve, who talked eloquently and passionately about the changes they’d made in the music, and about the jazz influences inspiring them. He spoke of his admiration for Elvin, Roy Haynes, Philly Joe Jones and Tony Williams and of studying their playing with his friend Lennie White, who had just joined Chick Corea’s Return to Forever. And he said something that struck me when I read the piece again the other day: “What’s so beautiful about the band, apart from the popularity which we know we’re fortunate to have and which we’re grateful for, is that right now it’s the perfect situation to be open. Specially at our age, because we realise that there’s still a lot of time.” Fifty years later, it’s clear the time hasn’t been wasted.

I loved Shrieve’s playing from the start, the way he meshed perfectly with the percussionists José “Chepito” Areas, Mike Carabello, Armando Peraza, Coke Escovedo and James Mingo Lewis. Since then I’ve followed his career mostly from a distance, although we reconnected when I was at Island Records in the mid-70s and he and Steve Winwood were part of Stomu Yamash’ta’s Go project, and then when the label signed Automatic Man, a rock band he was in with the singer/keyboards player Bayeté (Todd Cochran) and the guitarist Pat Thrall, and whose 1976 single “My Pearl” sounds today like a presentiment of Prince. Of his solo albums, I’ve always loved Stiletto, released in 1989 on RCA’s Novus imprint, in which he and a band including the trumpeter Mark Isham and the guitarists David Torn and Andy Summers created a very fine version of Gil Evans’s “Las Vegas Tango”.

If you have a copy of Lotus, the live triple album recorded in Osaka during the Caravanserai tour, you’ll know the 10-minute drum solo called “Kyoto” that shows what a superlative drummer he had already become, at the age of 23. It has none of the bombast of his rock contemporaries and much of the fluency of his jazz heroes. It’s music.

His new album, recorded over a period of years, is called Drums of Compassion — a reference to the hugely popular album titled Drums of Passion recorded in 1959 by the great Nigerian drummer Michael Babatunde Olatunji, who died at his home in Northern California 2003, aged 75, but whose voice is the one you hear first and again from time to time on an album that has been long in the making. Shrieve says that the title is also an acknowledgement of the Dalai Lama’s call for a Time of Compassion.

Of course, percussion instruments play an important role in this music. But the whole thing, although its 39 minutes are sub-divided into nine pieces, some with different composers, is like a lush, constantly shifting sound painting in which other instruments — guitar, saxophone, oud, electronic keyboards — emerge with utterances that seem less like solos than simply part of the fabric.

Shrieve can put together a multi-faceted track (“The Call of Michael Olantunji”) including himself, Jack DeJohnette, Airto Moreira and Zakir Hussain on various percussion instruments without making it sound for a second like an old-fashioned drum battle or a display of egos and techniques, even when Shrieve’s orchestral tom-toms come to the fore. The percussionists’ work is blended into the overall picture, here creating an armature for Olantunji’s voice and Trey Gunn’s guitar.

Shrieve can make the space for one performer alone on the eponymous “The Euphoric Pandeiro of Airto Moreira” (chanting and Brazilian percussion) and “Zakir Hussain” (tablas). He shares another track, the sultry, drifting “Oracle”, in a duet with another Brazilian, the electronic musician Amon Tobin. The ambience swirls and drifts without relaxing its subtle grip.

A steamy tone poem titled “On the Path to the Healing Waters” features the tenor saxophone of Skerik (Eric Walton), a Seattle-based musician who has played with Wayne Horvitz and Charlie Hunter, and who here plays a Wayne Shorter-ish less-is-more role. And I’m particularly happy to lose myself inside “The Breath of Human Kindness”, five minutes of one-chord jam in which the oud of Tarik Banzi makes its single eloquent appearance, a voice from ancient Al-Andalus amid the glistening keyboards of Pete Lockett and Michael Stegner, paced by Farko Dosumov’s stealthy bass guitar riff.

There’s a rare combination of majesty and humility at work in this music, something that speaks of the deep and lasting impact of Coltrane’s influence on Shrieve’s instincts and decisions. More than half a century after Caravanserai, this is an album for listeners who followed Shrieve and Santana on that journey into a wider world, one where frontiers and prejudices dissolve.

* Michael Shrieve’s Drums of Compassion is out now on the 7D Media label and available via Bandcamp: https://michaelshrieve7d.bandcamp.com/album/drums-of-compassion