Requiem for a soft-rocker

The members of the Association were still wearing suits and ties when they played the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, the opening act on a bill including Jimi Hendrix, the Who, Jefferson Airplane, Big Brother and the Holding Company and other heroes of the new counter-culture. Their qualification for inclusion might have been their first Top 10 single, “Along Comes Mary”, a three-minute proto-psychedelic masterpiece written by Tandyn Almer.

The follow-up, “Cherish”, a No. 1, had swiftly recast them as purveyors of soft-rock before the great “Pandora’s Golden Heebie Jeebies”, with its koto intro and inner-light lyric, earned praise from no less a psychedelic authority than Dr Timothy Leary, despite going no higher than No. 35. But then “Windy” (another No. 1) and “Never My Love” (No. 2) put them firmly back in the middle of the road, where they have remained in the public mind ever since.

Anyone interested enough to turn over “Never My Love”, however, found a B-side that restated their claim to hippie credibility. It was called “Requiem for the Masses” and it begins with military snare drum rolls introducing a choir singing acappella: “Requiem aeternam, requiem aeternam…” Then a young man’s voice sings the opening lines against an acoustic guitar: “Mama, mama, forget your pies / Have faith they won’t get cold / And turn your eyes to the bloodshot sky / Your flag is flying full / At half-mast…” The snare drum tattoo continues behind the second verse: “Red was the colour of his blood flowing thin / Pallid white was the colour of his lifeless skin / Blue was the colour of the morning sky / He saw looking up from the ground where he died / It was the last thing every seen by him…” The backing falls away and the unaccompanied choir returns: “Kyrie eleison, kyrie eleison…”

And here’s the chorus: “Black and white were the figures that recorded him / Black and white was the newsprint he was mentioned in / Black and white was the question that so bothered him / He never asked, he was taught not to ask / But was on his lips as they buried him.” The song ends with a lonely bugle against snare drum and muffled tom-tom.

In 1967 this song could be about only one thing: the war in Vietnam. Of course there already had been “Masters of War” from Dylan, “Universal Soldier” from Buffy Sainte-Marie and “Eve of Destruction” from P. F. Sloan. And perhaps “Requiem for the Masses” is not a truly great record, but it stands alongside things like Country Joe and the Fish’s “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag” and Earth Opera’s “The Great American Eagle Tragedy” as an ambitious and powerful contemporary statement from the world of white rock music.

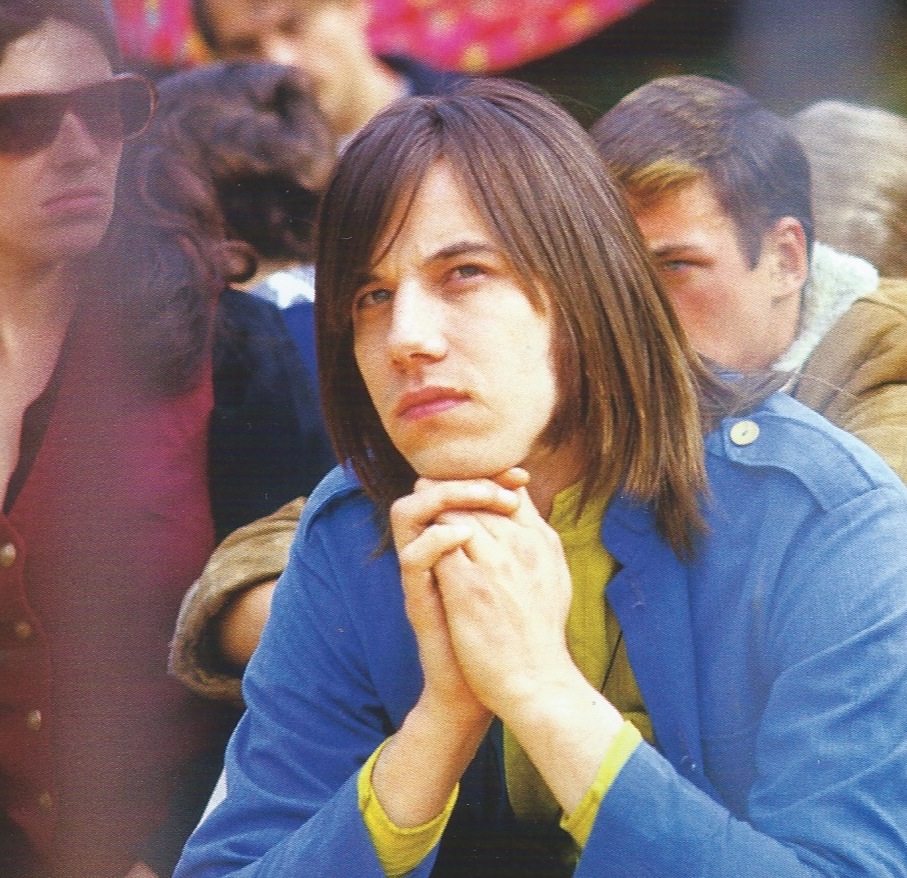

Its composer was Terry Kirkman, a founder member of the group, who sang, played percussion and brass and woodwind instruments (maybe including the bugle part). Before “Requiem for the Masses”, he had written “Cherish” and another soft-rock classic, “Everything That Touches You”. Born in rural Kansas, he was brought up in Los Angeles, where he studied music, but it was while working as a salesman in Hawaii that he met Jules Alexander, with whom he would go on to found several groups in LA, including the Inner Tubes (with Mama Cass and David Crosby), before the Association came together as a six-piece band in 1965. He left for the first time in 1972, returned in 1979, left again in 1984, and thereafter took part in various reunion concerts while working as an addiction counsellor.

Terry Kirkman died this week, aged 83. It would be absolutely wrong to underestimate the courage it must have taken for a band famous for their soft-rock hits to record such an unequivocal song of protest during a year in which the B52s were pounding Hanoi and Lyndon Johnson was sending ever more ground troops into the fight against the Vietcong, still with support from the majority of the American public. Respect to him, then.