Rainbows for Terry Riley

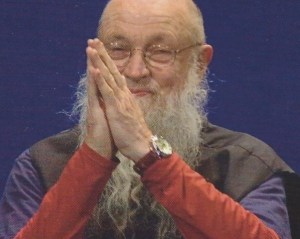

Terry Riley has been living in Japan for the past few years, passing on the teachings of Pandit Pran Nath in Kamakura, the country’s medieval capital, and Kyoto, the city of temples. Ahead of his 90th birthday on June 24, he announced this week that he’ll be scaling back his activities, handing his classes over to an acolyte while restricting himself to private lessons with advanced pupils.

On Thursday night the New York ensemble Bang on a Can All Stars, longtime performers of Riley’s work, arrived at the Barbican to celebrate his birthday by presenting two of his most famous compositions, with the help of several guests. Riley, of course, was 6,000 miles away, but he welcomed the audience warmly with a recorded video message transmitted via large screens.

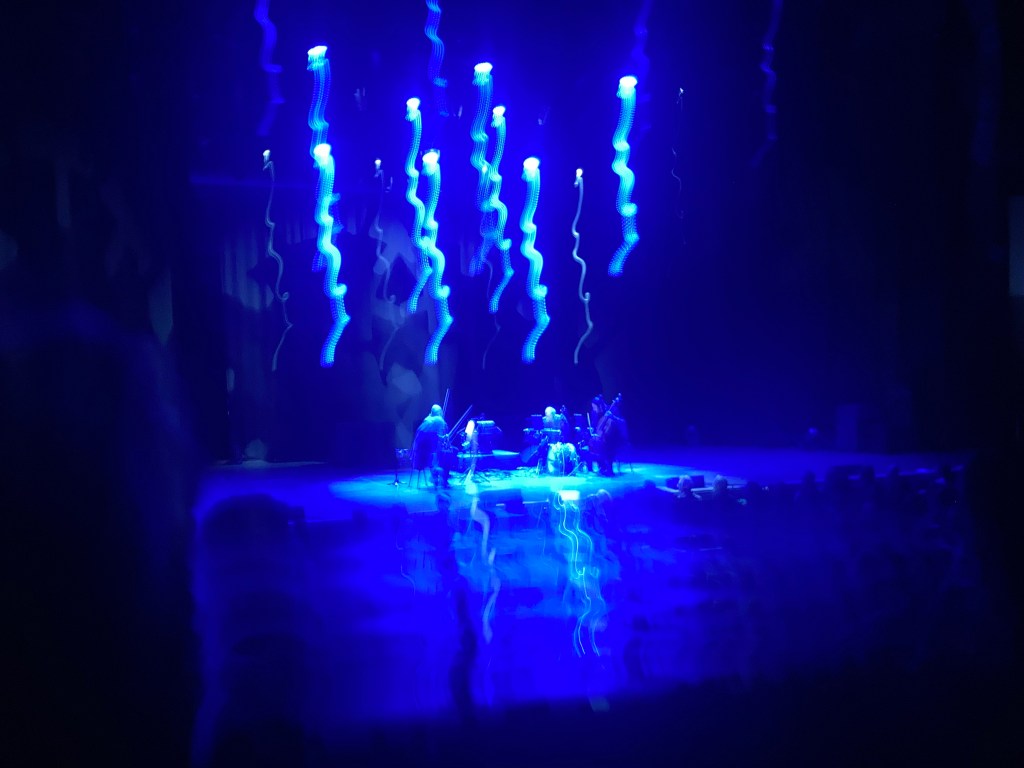

The evening began with the basic band — keyboard, clarinet/bass clarinet, electric guitar, cello, double bass and drum kit/vibes — performing A Rainbow in Curved Air, such a strong influence when it appeared in 1969 on the likes of Pete Townshend, Brian Eno and others experimenting with early synthesisers, although the original work itself was performed by Riley on organ, electric harpsichord, rocksichord, dumbec and tambourine, via overdubs.

Arranged for the sextet by Gyan Riley, Terry’s son, and slightly stretched from the original 19 minutes to 25, it preserved the sense of genially interlocking patterns, although Riley’s 14-beat measures seemed to have become a distinct 7/4, strongly articulated by the group’s drummer, David Cossin, before he switched to vibes for the later passages. The sudden halts and resumptions were as gently startling as they seemed on the album five and a half decades ago.

In C, first performed in 1964 and recorded in 1968, is the piece that made Riley’s reputation in the world of contemporary classical music. A remarkably versatile composition, open to any number of players and all musical instruments in any combination, its 53 modules — short musical phrases using all 12 tones of the tempered scale except C sharp and E flat — must be played in order but can be repeated according to each performer’s feeling for the piece’s overall collective development. For last night’s 65-minute performance, Bang on a Can were joined by Shabaka on flutes, Valentina Magaletti on marimba, Soumik Datta on sarod, Portishead’s Adrian Utley on guitar, Raven Bush on violin, Gurdain Rayatt on tablas and Jack Wyllie on soprano saxophone. (Pete Townshend was billed to appear but withdrew following a knee operation.)

I found the result entirely true to the original spirit of the composition, preserving the constant momentum and the sense of conversation without the presence of a conductor. The instrumentation produced wonderful fluctuations of density and shifting polyrhythmic layers; there were beautiful isolated moments, like a brief sarod/cello combination and the emergence of a clarinet melody, and the general lightness of tone brought the closing passage close to the texture of baroque music.

It was like lying on your back and watching clouds moving at a variety of altitudes across a busy but unthreatening sky, endlessly mutating and utterly absorbing until it was brought, with an act of intuitive collective decision, to the most graceful close. Happy birthday, Mr Riley.

One of the great qualities of Terry Riley’s In C, a foundational work of modern music, is that it can be played by any number of people using any kind of instruments for as long as they choose to make its sequence of 53 motifs last. Since the appearance of the original album in 1968 it has been recorded by a wide variety of ensembles, including the Shanghai Film Orchestra, Acid Mothers Temple, the Salt Lake Electric Ensemble, Adrian Utley’s Guitar Orchestra, and Africa Express with Damon Albarn and Brian Eno. The original album version lasted 42 minutes, but it can be made to go on much longer. (I haven’t heard of an attempt to compress it into the length of a 45rpm single, but I’ll bet someone’s had a go.)

One of the great qualities of Terry Riley’s In C, a foundational work of modern music, is that it can be played by any number of people using any kind of instruments for as long as they choose to make its sequence of 53 motifs last. Since the appearance of the original album in 1968 it has been recorded by a wide variety of ensembles, including the Shanghai Film Orchestra, Acid Mothers Temple, the Salt Lake Electric Ensemble, Adrian Utley’s Guitar Orchestra, and Africa Express with Damon Albarn and Brian Eno. The original album version lasted 42 minutes, but it can be made to go on much longer. (I haven’t heard of an attempt to compress it into the length of a 45rpm single, but I’ll bet someone’s had a go.)