The return of Pete Atkin

It’s often said, with an air of puzzled regret, that Britain lacks the equivalent of chanson. We certainly had an influential Anglo-Scottish folk tradition, and we had the Beatles and Radiohead. But we didn’t exactly have a Georges Brassens, a Léo Ferré or a Jacques Brel. There never seemed to be a market for that kind of grown-up, ballad-based popular music. Some might say that Jake Thackray, the sardonic, saturnine Yorkshireman who died 20 years ago, came the closest. Others would make the case for Pete Atkin, who emerged at the end of the 1960s singing songs in which he put the melodies to the lyrics of Clive James, and who returned to live performance at the Pheasantry in Chelsea on Saturday night.

For a few years at the beginning of the ’70s, it looked as though Atkin and James, who had met as members of the Cambridge Footlights, might be on the brink of some sort of commercial success with albums such as Beware of the Beautiful Stranger, Driving Through Mythical America and A King at Nightfall. But things tended to get in the way. One example would be Kenny Everett getting sacked from the BBC for making a joke about a cabinet minister just as he was playing one of their songs every week on his Radio 1 show.

Another might be James becoming famous for his weekly Observer TV review, in which he found his comic voice. Polyglot, polymathic, he translated Dante, wrote a series of best-selling memoirs, hosted an annual Formula 1 review on TV, befriended Princess Di, and took tango lessons in Buenos Aires. Atkin, for his part, had a long and award-winning career with BBC Radio as a script editor, producer and head of network radio in Bristol — as well as voicing the part of Mr Crock in a Wallace & Gromit movie. In the early 2000s they reunited and toured together, writing new songs before James succumbed to leukaemia in 2019.

Atkin’s dry, classless English voice was always a long way from the tone of his male singer-songwriter contemporaries produced by the English folk scene, from Ralph McTell to Nick Drake. Lacking any hint of assumed American inflection, his delivery suited James’s agile, witty and erudite lyrics, even though James took so much of his subject matter from American popular culture. Together they aimed for a modern take on the great Broadway songwriting partnerships, absorbing the pop-culture influences of their own time alongside historical references just as their predecessors had. Cole Porter’s “You’re the Top” — “You’re an old Dutch master / You’re Mrs Astor” — might have been their template.

It’s a combination that appealed to a certain sensibility, one well represented at the Pheasantry, where Atkin was making a rare appearance in order to launch a new CD, The Luck of the Draw, the second volume of revisions of some of the old songs and a handful of hitherto unrecorded collaborations (the first, Midnight Voices, was released in 2007).

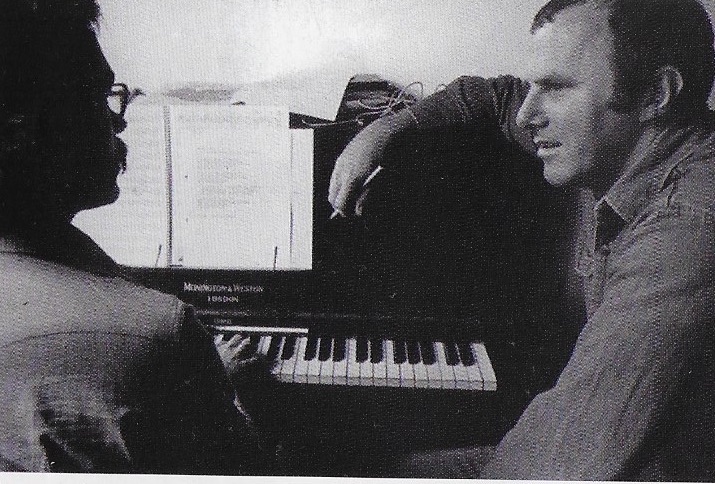

He sang and played guitar, accompanied for much of the time by Simon Wallace’s beautifully fluent piano. Wallace is one of the musicians on the new album, along with an A-team of Nigel Price on guitar, the bassist Alec Dankworth, Rod Youngs on drums, Gary Hammond on percussion and the saxophonist Dave O’Higgins, together reupholstering the older songs with care and imagination. (Atkin and James always had good taste in musicians: Chris Spedding, Kenny Clare, Alan Wakeman, Tony Marsh and Herbie Flowers were among the supporting cast on the early albums.)

The dramatic highlights of the live set were “Beware of the Beautiful Stranger” and “The King at Nightfall”, two songs for which Atkin, as was his underrated habit, found melodies at least the equal of the beguiling lyrics. The latter’s portrayal of a fallen and hunted despot, its title taken from a line in Eliot’s “Little Gidding”, seems even more resonant today than it was in 1973.

Sometimes James’s erudition could be stretched a bit thin in pursuit of wittiness, as in “I’ve seen landladies who lost their lovers at the time of Rupert Brooke / And they pressed the flowers from Sunday rambles and then forgot which book” (from “Laughing Boy”). During the show Atkin mentioned that the lyricist had self-critically dismissed “The Only Wristwatch for a Drummer” as an example of his own tendency to show off, and I suppose the same charge could be levelled at things like “Screen-Freak”, with its kaleidoscope of Hollywood images, or “Together At Last”, which plays games with pairs (“Two-gether at last / Hearts that beat as one / Swift and Stella, Perry and Della / Dombey and Son”). But they’re audience-pleasers, a facet of a talent that incorporated the audacity required to attempt something like “Canoe”, in which two time-frames, pre-technology and space age, are seamlessly blended.

In my view, James was at his very best at a provider of song lyrics when he was expressing deep emotion in relatively simple language. This was perfectly displayed in three songs Atkin performed at the Pheasantry, each of them a lament for love departed or unanswered. Atkin described the first of them, “An Empty Table”, as resembling a film, shot part in black and white and part in colour, the unadorned lyric perfectly matched by a tune which begins from an unexpected trajectory, then soars and settles with unassuming elegance. The second, “The Trophies of My Lovers Gone”, takes its title from Shakespeare’s Sonnet XXXI, its search for a complex emotional truth reflected in a melody that wanders gracefully. The third, “Girl on a Train”, more typical of James in that the girl he’s yearning after is absorbed in a volume of Verlaine, was presented on Saturday as a final encore, finishing the evening with an elegiac cadence of guitar and piano, drifting into silence.

* Pete Atkin’s The Luck of the Draw is released on the Hillside label (www.peteatkin.com). Ian Shircore’s book Loose Canon: The Extrordinary Songs of Clive James & Pete Atkin, first published in 2016 by RedDoor and now in paperback, is also recommended.