Outer and inner space

On the 243 bus ride to yesterday’s matinee show at Cafe Oto, I finished Samantha Harvey’s short novel Orbital, the winner of this year’s Booker Prize. Starting as a description of the lives of six astronauts aboard a space station, it finishes as a meditation on the world — the planet, the universe — and our place in it.

With that in my head, listening to Evan Parker, Matthew Wright and their four colleagues in this edition of Transatlantic Trance Map create their intricate musical conversations was like zooming in on the smallest level of earthly detail: an example of our human potential, in the face of cosmic irrelevance.

For two shortish sets of unbroken free improvisation, Parker (soprano saxophone) and Wright (turntables and live sampling devices) were joined by Hannah Marshall (cello), Pat Thomas (electronics), Robert Jarvis (trombone) and Alex Ward (clarinet). The music was calm, collective, and often very beautiful in its constant warp and weft. Maybe it was the occasional (very subtle and always appropriate) pings and hums from the electronics that reinforced the connection in my mind with Orbital: the whoosh of a closing airlock, the light clang of a piece of space junk against a titanium hull. But that was obviously just me.

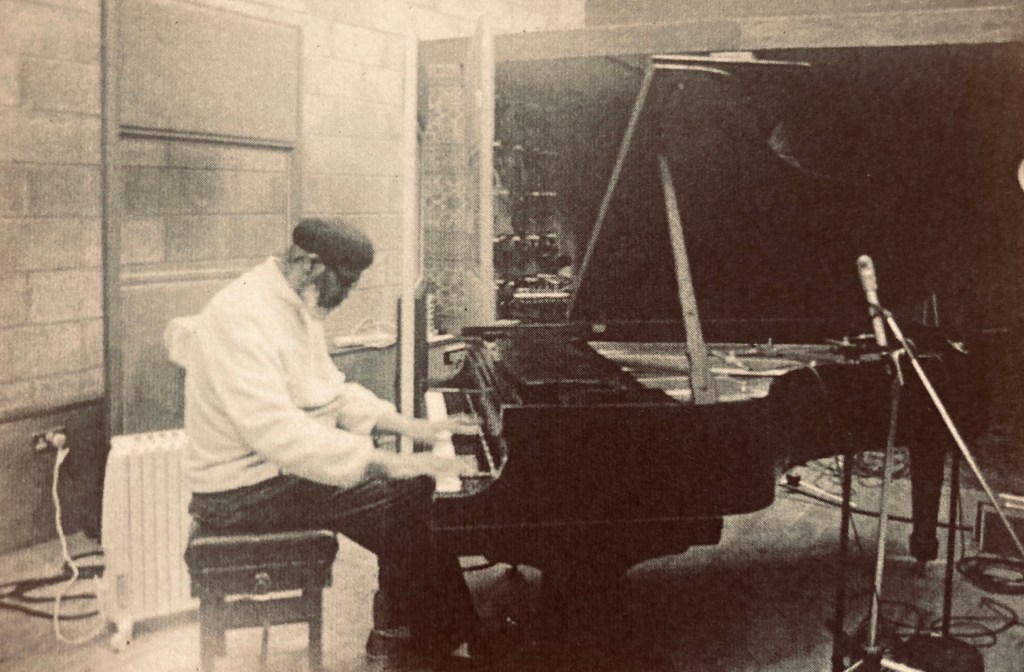

Many years ago I went to interview Evan at his home in Twickenham. One thing I noticed was that his shelves of LPs had a particularly long stretch of orange and black spines: John Coltrane on the Impulse label, of course. Evan has never sounded like Coltrane, but his study of the great man was foundational to his own development and his interest remains deep. Yesterday, for example, he was keen to tell me about the extraordinary sound quality of the reissue of the 1962 Graz concert by Coltrane’s classic quartet on Werner Uehlinger’s ezz-thetics label. “You can hear the ping of Elvin’s ride cymbal,” he said.

So it was by an interesting coincidence that I went on from Dalston to another event on the last day of the EFG London Jazz Festival, a concert at the Queen Elizabeth Hall called Coltrane: Legacy for Orchestra. For this performance of arrangements by various hands of some of Coltrane’s compositions (“Impressions”, “Central Park West”, “Giant Steps”, “Naima” etc), and a few other pieces that he recorded (including “So What”, “Crepuscule with Nellie” and “Blue in Green” and a handful of standards, including “My Favourite Things”), the full BBC Concert Orchestra, conducted by Edwin Outwater, was joined by two horn soloists, the young American trumpeter Giveton Gelin and the experienced British saxophonist Denys Baptiste, and the trio of the pianist Nikki Yeoh, with Shane Forbes on drums and Ewan Hastie on bass.

Inevitably, I suppose, there were times when it felt as though Coltrane was being reduced to something close to light music; there was certainly no attempt to get to grips with the turbulence of the music he made in the last three years of his life in albums such as Interstellar Space. But there were moments of distinction, too. Baptiste tore into “Impressions”, while Gelin — a New York-based Bahamian in his mid-twenties — earned ovations for his poised reading of “My One and Only Love” and for a lovely coda to “In a Sentimental Mood”, mining the elegant post-bop tradition of Clifford Brown, Lee Morgan and Freddie Hubbard.

In terms of the response from a full house, it was a great success. But there was one moment when the music went deeper, closer to what Coltrane was really about, and it came in the arrangement of “Alabama” by Carlos Simon, a composer in residence at the John F. Kennedy Centre for the Performing Arts in Washington DC, and the principal begetter of this project.

“Alabama” is Coltrane’s most sacred song, a slow, heavy hymn to the memory of the four African American schoolgirls murdered by racists in the bombing of a church in Birmingham, Alabama on September 15, 1963. Simon chose to orchestrate it in the way Eric Dolphy and McCoy Tyner might have done, had it been written in time for inclusion in 1961 in Coltrane’s first Impulse album, Africa/Brass, on which Dolphy and Tyner made dramatic use of low brass.

Here, Simon added trombones and French horns, using tympani and a gran cassa to augment Shane Forbes’s mallets on his tom-toms, thus amplifying the effect of Elvin Jones’s original rolling thunder behind Baptiste’s emotionally weighted statements of the rubato theme. Like the tenorist’s extended but carefully shaped solo on the in-tempo passage, it honoured not only Coltrane’s memory but his intentions, and will be worthy of special attention when Radio 3 broadcasts the concert later this week.

* Transatlantic Trance Map’s album Marconi’s Drift is out now on the False Walls label (www.falsewalls.com), which is also about to release a four-CD box set of Evan Parker’s solo improvisations, titled The Heraclitean Two-Step, Etc. The live recording of Coltrane: Legacy for Orchestra will be broadcast on BBC Radio 3 between 19:30 and 21:45 on Thursday 28 November, thereafter available on BBC Sounds.

If I were given the freedom to design a place at which people could gather for the purpose of playing and hearing music, it would probably end up very much like Cafe Oto. Some of the Dalston venue’s features include an entrance straight off an interesting side street, chairs and tables on the pavement for use during the intervals between sets, large picture windows to give passers-by a glimpse of the goings-on inside, an informal and intimate performance space with no stage, with discreet lighting and perfect sound, a good piano, the option to sit or stand, unselfconscious interaction between musicians and listeners, excellent refreshments, bike parking. And, most important, an audience equipped with open ears and minds, not drawn from a single demographic.

If I were given the freedom to design a place at which people could gather for the purpose of playing and hearing music, it would probably end up very much like Cafe Oto. Some of the Dalston venue’s features include an entrance straight off an interesting side street, chairs and tables on the pavement for use during the intervals between sets, large picture windows to give passers-by a glimpse of the goings-on inside, an informal and intimate performance space with no stage, with discreet lighting and perfect sound, a good piano, the option to sit or stand, unselfconscious interaction between musicians and listeners, excellent refreshments, bike parking. And, most important, an audience equipped with open ears and minds, not drawn from a single demographic.