The flight of Mike Osborne’s alto saxophone was like that of the swift: its entire existence was spent on the wing, soaring high or swooping in shallow dives, twisting back on itself before arcing again towards the heavens, as if desperate to avoid contact with the ground.

Something remarkable was happening in London in the early ’70s, at places like the 100 Club, the Phoenix in Cavendish Square, the Plough in Stockwell, and Peanuts, a regular session run by Osborne at a place near Liverpool Street station. A few dozen young musicians, most of whom had emerged late in the previous decade as sidemen in the bands of Mike Westbrook, Chris McGregor, Graham Collier and John Stevens, were now playing together in shifting combinations. The economics of jazz dictated a preference for small groups, and one of the most remarkable was Osborne’s trio, completed by two South African emigrés, Harry Miller on bass and Louis Moholo on drums.

What I remember from that scene is the absolute lack of pretension. There was no interest in surfaces or self-presentation. The musicians appeared before the audience wearing the clothes they’d arrived in. There wasn’t much in the way of introducing or explaining — but neither was there the kind of self-conscious detachment that even someone as natural as the bassist Dave Holland, once a member of that London scene, felt compelled to adopt on stage when he crossed the Atlantic and joined Miles Davis.

On the bandstand, the Mike Osborne Trio was typical of its time and milieu in that there was only one priority: to burn. Strategies learnt from Coltrane, Coleman and Ayler were bent to their own ends, creating a platform for their own individual voices. Osborne loved Ornette and Jackie McLean, his fellow altoists (I remember a copy of the latter’s great Blue Note LP Destination…Out! propped beside the record player in his flat when I interviewed him in 1970), but he became one of the era’s great originals on his instrument.

Sadly, his own era didn’t last long. In 1959 he arrived from Hereford as an 18-year-old to study at the Guildhall in London. Fifteen years later he suffered a breakdown at the end of a six-week gig at the Paris Opéra, where he had played onstage for a ballet alongside the other two members of the group SOS, his fellow saxophonists Alan Skidmore and John Surman. Prolonged treatment meant that there would be only sporadic gigs until 1982, when he returned to Hereford, his playing days at an end. He died of cancer in 2007, aged 65.

His discography is not huge, but it is of extraordinary quality, whether in sessions with Westbrook, SOS, the one-off quartet of the trumpeter Ric Colbeck, Surman’s octet, the big bands of Kenny Wheeler and John Warren, Miller’s Isipingo, McGregor’s Brotherhood of Breath, or a duo with Stan Tracey. And now there’s a wonderful addition in the shape of a session said to have been recorded (surprisingly well) at the 100 Club in December 1970, where Ossie, Harry and Louis were joined by Skidmore to make a fire-breathing quartet of ferocious intensity but immaculate balance.

As I remember him, Ossie always played with his eyes closed, everything else shut out. His tone is at its most beautiful on this session, whether making an assembly of staccato phrases or, more frequently, sliding through faster-than-light near-glissandi that never lose coherence or a sense of proportion. At this stage of his life, his emotions had located the perfect musical register. No wonder, after he had dropped out of SOS, Surman and Skidmore found him impossible to replace, and the group’s own short life was over.

On a winter’s night in an Oxford Street basement in 1970, Skidmore, Miller and Moholo matched him every step of the way, and Starting Fires is a very appropriate title for an album containing 40 minutes of music that never lacks light and shade but is driven by its unwavering sense of purpose. Short, epigrammatic themes appear and then dissolve, giving shape to the performance. Near the beginning and again towards the end, the two horns improvise together quite brilliantly, twining and tangling with complete commitment. It’s life-and-death stuff, which is how so much of this music felt at the time, and never more so than when Mike Osborne was on the stand.

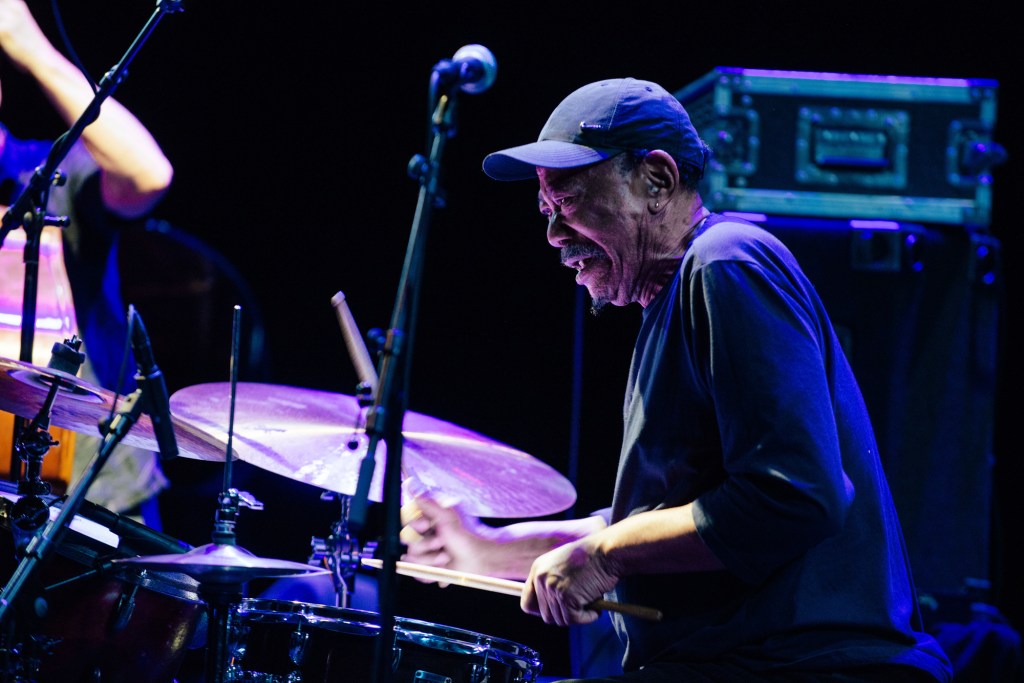

* Mike Osborne’s Starting Fires: Live at the 100 Club 1970 is out now on the British Progressive Jazz label. I don’t know who took the photograph. My Guardian obituary of Osborne is here.