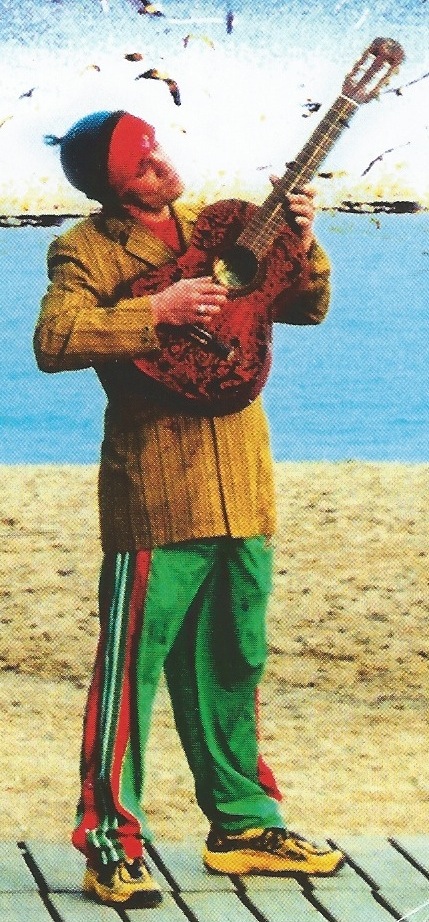

Manu Chao in London

The advance publicity described Manu Chao’s show at Brixton Academy last night as an acoustic set, but if that suggests some kind of gentle fireside recital, forget it. The energy was peaking from the moment the 63-year-old Franco-Spanish singer-guitarist appeared — with Lucky Salvadori from Argentina playing what I think was a Colombian tiple and Miguel Rumbao from Havana playing bongos and activating a little black box that triggered the whistles, sirens and other effects that are the essential ambient noise of Chao’s music.

Actually, the energy was high well before the band showed up, thanks to a capacity audience whose anticipatory chatter set the vibe. It was a polyglot crowd, predominantly made up of expatriates and exiles and perhaps even refugees, speaking at least as many languages as those in which Chao sings — Spanish, French, Italian, Portuguese, English — and the richness of the sound they made while waiting for the music to start was an audible manifestation of that multicultural make-up.

Chao’s second or third song in a two-hour set was “La Vida Tombola”, his wonderful ode to Diego Maradona. He sang it, then paused, and sang it again, and paused, and sang it again. And so on. It may have continued in that fashion for 20 minutes. Long enough for me to suggest to my companion that perhaps he was going to carry on singing it all night. We agreed that this would be fine with us.

He didn’t, but many of the other songs got a similar treatment. “Clandestino”, “Me Gusta Tu”, “El Viento”, “Bongo Bong” — each seemed full of false endings and fresh starts. It was as though every song, some of them featuring a two-man horn section of trumpet and trombone, came with its own built-in encores. And each time the strumming began again, your own heartbeat seemed to restart itself.

There was a lot of audience participation, of the sort that happens at a Bruce Springsteen concert, when everyone sings the first verse of “Hungry Heart”. Unlike me, most of last night’s audience seemed to be word-perfect on every song. In the immediate aftermath, as we made our way slowly down the stairway to the exit, all bathed in Chao’s special warmth, a happy throng burst into the last nonsense chant we’d been singing with him.

This was his first show in London in 14 years, which perhaps explains some of the fervour with which he was greeted. For once, I got home not wanting to play the recorded versions of the songs I’d just been enjoying live but instead to listen again to his new album, Viva Tu, his first since La Radiolina in 2014.

It’s a gentler and more intimate version of his usual approach, reflecting his words in the accompanying press release, in which he mentions the influence skiffle had on him. Whatever, it’s full of beautiful songs, including two duets — the lilting “Tu Te Vas” with Laeti and “Heaven’s Bad Day” with Willie Nelson, an inveterate duetter even in his 10th decade — and the gorgeous “Cuatro Calles”. Like last night’s concert, it draws you in, making you — and the whole world — feel included.

* Manu Chao’s Viva Tu is out now, released through Because Music.