Café Society in wartime

`

I imagine I picked up a copy of Life magazine’s edition of October 16, 1944 from a flea market many years ago because its cover featured the 20-year-old Lauren Bacall, making her screen debut in To Have and Have Not opposite Humphrey Bogart: “Midway through the first reel the sulky-looking girl shown on the cover saunters with catlike grace into camera range and in an insolent, sultry voice says, ‘Anybody got a match?'”

But along with that, I got something that now seems much more interesting.

Between full-page ads for Packard and Pontiac cars, Texaco oil, Budweiser beer, National Dairy, Stromberg-Carlson radios and Chesterfield cigarettes, all using the military as a motif and/or urging citizens to buy war bonds, there’s a story describing how, in New York, “hotels are booked solid for weeks in advance and guests spend more money” and “the boom reaches a peak in the sale of luxury goods at department stores.” In a month when Allied troops are fighting their way into Germany, this is part of report on the vigorous economic upsurge created by the US participation in the Second World War.

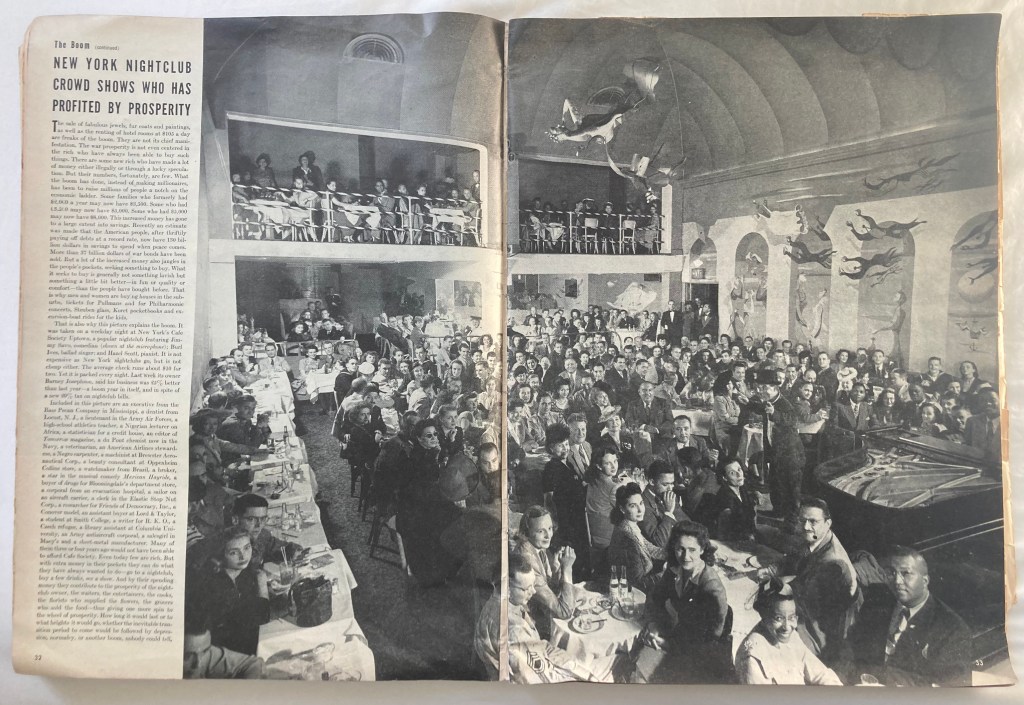

To illustrate the upbeat mood, the editors present a double-page spread on a flourishing nightclub, Café Society Uptown. Located on East 58th Street, between Lexington and Park Avenues, it’s an adjunct to the original Café Society on Washington Square in Greenwich Village. Both were run by Barney Josephson, who booked Billie Holiday for opening night in 1938 at the Village establishment, where she would sing “Strange Fruit” for the first time a year later. The second club opened in 1940. Both were notable for the welcome they extended to all races.

The current attractions at the East 58th Street joint in the autumn of 1944 were the fine jazz pianist Hazel Scott, the folk singer Burl Ives and the comedian Jimmy Savo, who can be seen at the microphone. Higher wartime wages meant that business was up 25 per cent on the previous year, so Josephson told the magazine, and patrons were spending an average of $10 a head.

I could spend hours scanning the faces looking up at the lens deployed at a high angle by Herbert Gehr, a German-Jewish photographer who had escaped Nazism and photographed the Spanish Civil War before arriving in the US, where he joined the staff of Life. I wish there were a key giving the details of each individual in the teeming frame. But the magazine’s caption writers do their best in giving us an anonymised but still vivid snapshot of the diversity of the evening’s audience:

“Included in this picture are an executive from the Bass Pecan Company in Mississippi, a dentist from Locust, N. J., a lieutenant in the Army Air Forces, a high-school athletics teacher, a Nigerian lecturer on Africa, a statistician for a credit house, an editor of Tomorrow magazine, a du Pont chemist now in the Navy, a veterinarian, an American Airlines stewardess, a Negro carpenter, a machinist at Brewster Aeronautical Corp., a beauty consultant at Oppenheim Collins store, a watchmaker from Brazil, a broker, a star in the musical comedy Mexican Hayride, a buyer of drugs for Bloomingdale’s department store, a corporal from an evacuation hospital, a sailor on an aircraft carrier, a clerk in the Elastic Stop Nut Corp., a researcher for Friends of Democracy, Inc., a Conover model, an assistant buyer at Lord & Taylor, a student at Smith College, a writer for R. K. O., a Czech refugee, a library assistant at Columbia University, an Army anti-aircraft colonel, a salesgirl in Macy’s and a sheet-metal manufacturer.”

I’ve been trying to spot the “Conover model”, who would have been someone on the books of the agent Harry Conover. His roster included Eugenia “Jinx” Falkenburg, a former Hollywood High School student who posed for Edward Steichen, was named “Miss Rheingold” in a series of beer ads, and by 1944 had became famous enough to play herself alongside Rita Hayworth and Gene Kelly in Charles Vidor’s romantic comedy Cover Girl, with songs by Jerome Kern and Ira Gershwin. Four years later her younger brother Bob would win the Wimbledon men’s singles title. Maybe Jinx is there in the crowd.

But the conclusion reached by the caption writers, pursuing the theme of a wartime boom, is this: “Many of them three or four years ago would not have been able to afford Café Society. Even today few are rich. But with extra money in their pockets they can do what they have always wanted to do — go to a night club, buy a few drinks, see a show. And by their spending money they contribute to the prosperity of the night-club owner, the waiters, the entertainers, the cooks, the florists who supplied the flowers, the grocers who sold the food — thus giving one more spin to the wheel of prosperity. How long it would last or to what heights it would go, whether the inevitable transition period to come would be followed by depression, normalcy or another boom, nobody could tell.”