The moment of Joy

After a great deal of activity on the British jazz scene of the early 1970s, things were starting to go quiet by the time a quintet called Joy came along. The generation centred on Mike Westbrook, Graham Collier, Keith Tippett, Howard Riley, the Spontaneous Music Ensemble and the Blue Notes had flared brightly before settling down for the longer haul. Around the corner in the next decade would be the media attention given to the new wave of Courtney Pine, Andy Sheppard, Loose Tubes and the Jazz Warriors. Caught in the middle, Joy appeared at a time when the spotlight was pointed elsewhere.

Joy had nothing to do with fashions in jazz. They were untouched by fusion, for instance. They played acoustic music, keeping the flame alive without turning it into the sort of purist mission proclaimed by the Marsalis brothers a few years later. Perhaps they were also among the last young jazz musicians to take the stage wearing what they’d put on when they got up that morning. There was no image, no marketing campaign.

I remember being convinced even before the group came together in 1976 that two of their members in particular, the drummer Keith Bailey and the alto saxophonist Chris Francis, both born in 1948, were destined to become stars. I’d heard Bailey when he followed Ginger Baker and Jon Hiseman into Graham Bond’s band, and felt immediately that he was something special: he had a quality — a lithe swing combined with all the power he needed — that I found again the first time I heard Moses Boyd, 40 years later. The extravagantly talented Francis combined bebop chops with Mike Osborne’s emotionality (filtering Jackie McLean’s sweet sourness) and Dudu Pukwana’s cry. Both spoke their chosen language as if they’d been born to it.

The other members of the band were the draft-dodging American trumpeter Jim Dvorak, the South African bassist Ernest Mothle and the very fine London-born pianist Frank Roberts, the youngest of the five. All except Mothle contributed compositions to the self-titled album they made in 1976 for Cadillac Records, founded by the late John Jack and now celebrating its 50th anniversary. What turned out to be Joy’s only release is among the albums reissued to celebrate the label’s golden jubilee, restored and remastered for CD and digital release with the addition of unedited and unreleased tracks.

As Bailey says in the sleeve notes, Joy played straight-ahead modern jazz, stepping aside from the adventures in freedom in which others were engaged. Imagine a young Horace Silver Quintet, with an infusion of the Blue Notes’ irresistible townships flavour and touches of modal jazz as refined by Herbie Hancock: you could have plonked them down anywhere in the world, from New York to Tokyo, and they would impressed the most sophisticated of modern jazz audiences.

After Joy disbanded, Francis spent some years as a photographer; he now lives in Surrey, where he plays and teaches. Bailey moved to the US in 1980, briefly studied drums with Andrew Cyrille and composition with Morton Feldman, and is based in Santa Fe; he stopped playing regular drums in 1986, in order to concentrate on solo percussion recitals. Frank Roberts remained active on the London scene for many years and is now based in Aarhus, Denmark. Jim Dvorak, having appeared with the Dedication Orchestra and Keith Tippett’s Mujician, continues to play and work in London. Ernest Mothle, whose strength and inventiveness made him the fulcrum of the quintet, appeared with his old friends Hugh Masekela and Jonas Gwanga at Nelson Mandela’s 70th birthday concert at Wembley in 1988 before returning to South Africa, where he died in Pretoria from diabetes-related conditions in 2011.

As young musicians together, for an all too brief span of time in the 1970s, they had something special going. Their album is a pungent and vivid reminder of its time, but more than deserves its place in the present.

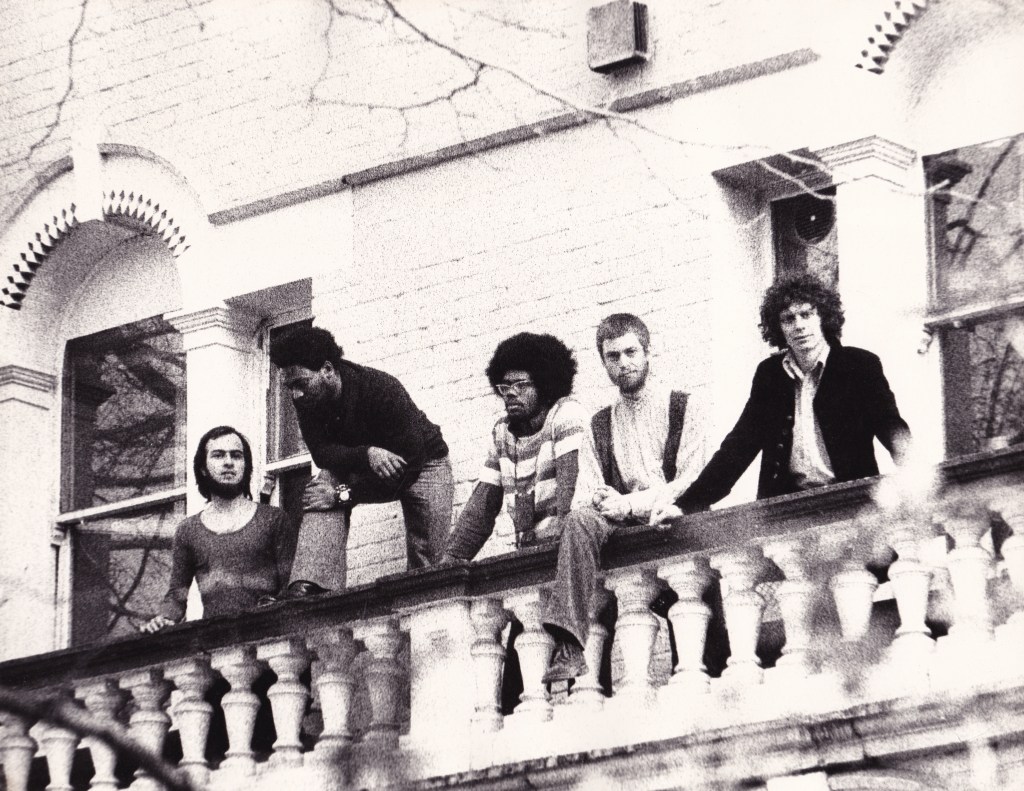

* The photograph of Joy is by the late Jak Kilby. Left to right: Jim Dvorak, Ernest Mothle, Frank Roberts, Keith Bailey and Chris Francis. The album is out now on the Cadillac label: cadillacrecords77.com

Jazz never had a more faithful friend than John Jack, who died on September 7 and whose life was celebrated at the 100 Club yesterday, following a committal at the Islington and Camden/St Pancras crematorium. Among those musicians and poets queuing up to pay tribute by through performance were Mike Westbrook and Chris Biscoe (pictured during their duet), Evan Parker and Noel Metcalfe, Jason Yarde and Alexander Hawkins, Steve Noble (with Hogcallin’, one of John’s favourite British bands), Pete Brown and Michael Horovitz. Many others were present, along with scores of faces familiar from countless nights in dozens of clubs down the years, all of us having trouble believing that we won’t be seeing John again with his beloved Shirley at their usual table in the Vortex.

Jazz never had a more faithful friend than John Jack, who died on September 7 and whose life was celebrated at the 100 Club yesterday, following a committal at the Islington and Camden/St Pancras crematorium. Among those musicians and poets queuing up to pay tribute by through performance were Mike Westbrook and Chris Biscoe (pictured during their duet), Evan Parker and Noel Metcalfe, Jason Yarde and Alexander Hawkins, Steve Noble (with Hogcallin’, one of John’s favourite British bands), Pete Brown and Michael Horovitz. Many others were present, along with scores of faces familiar from countless nights in dozens of clubs down the years, all of us having trouble believing that we won’t be seeing John again with his beloved Shirley at their usual table in the Vortex.