At Peggy’s Skylight

Some jazz clubs are intimidating to the first-time visitor, and maybe that’s how they’re supposed to be. Not all of them, though. I’d been meaning to visit Peggy’s Skylight in Nottingham for ages, and on Saturday afternoon I walked in there for the first time and felt right at home.

A Saturday afternoon might seem an odd time to visit a jazz club. But I’d just got off the train from London, with a couple of hours to spare in my old home town before the start of the football match I’d come up to see, so I walked from the station to George Street, just off Hockley, a narrow but always busy street on the edge of the historic Lace Market.

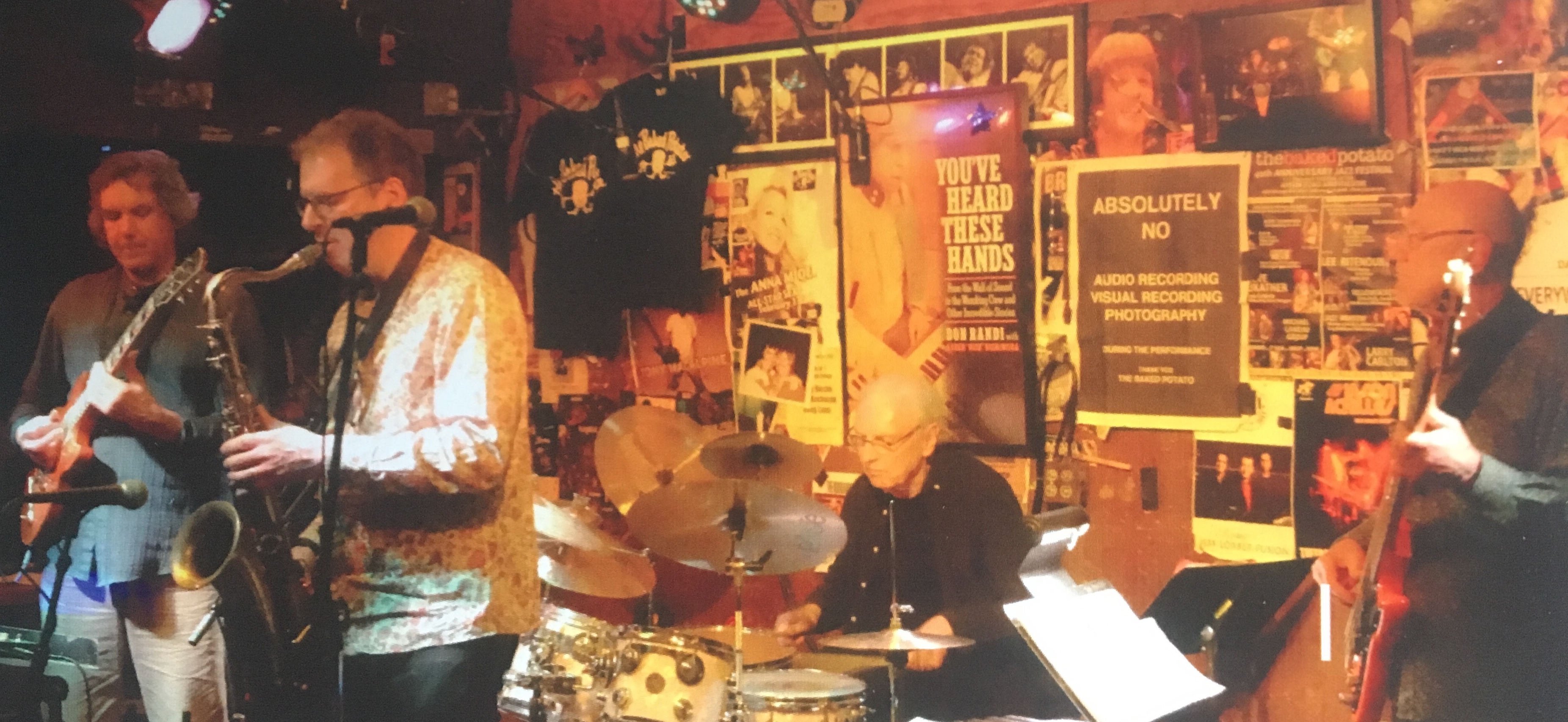

Peggy’s Skylight occupies the double-frontage of a nice old building. The club was opened in 2018 by Rachel Foster and Paul Deats, and it’s named after Charles Mingus’s “Peggy’s Blue Skylight”; you can see a visual reference above the bandstand in the photo. The Mingus track was recorded in 1961 and featured Roland Kirk, who in 1964 played a concert one street away from where Peggy’s now stands, at the Co-operative Arts Centre on Broad Street (I wrote about it here and here).

On Saturday afternoons Peggy’s has an Unplugged session, with free admission. Deats was playing piano when I walked in. He was sharing the stage with a seriously good local tenor saxophonist, Ben Martin, and they were playing “My One and Only Love”, one of my favourite ballads. The room was full, and I was lucky that they could find me a seat. People of several generations were eating, drinking, chatting and occasionally checking their phones while Martin and Deats produced accomplished, unflashy, nicely proportioned duets that were soon putting me in mind of how Hank Mobley and Tommy Flanagan might have sounded together.

At this session, the music had a different vibe. It was part of a social setting, absorbed in a way that didn’t devalue it at all. If you wanted to listen to as good version of “Alone Together” as you’re likely to find this side of Jo Stafford, or a lively “On the Sunny Side of the Street”, you could do happily do so, joining the warm applause at the end of each tune. But the voices from the tables around you were part of the environment. It wasn’t like that oaf guffawing for posterity over Scott LaFaro’s final notes on the Bill Evans Trio’s sublime version of “Milestones” at the Village Vanguard in 1961. Here, the ambient sounds were perfectly natural and unobtrusive.

Normally I don’t like eating while I listen to music, and I’m not much interested in food anyway. But I was hungry and it seemed fine to enjoy an excellent pan of eggs with harissa while keeping my ears open. (Deats is also a chef, and Peggy’s menu has a North African and Middle Eastern tilt.)

Last year the club’s partners were required to resist plans to sell the building by the local council, which owns the freehold and has recently become one of several around England to announce its own bankruptcy. The day before I walked in had brought news the reduction of the city’s entire culture budget to zero. Nottingham Playhouse, opened with great pride 60 years ago almost to the month and whose artistic directors included John Neville and Richard Eyre, will see its council subsidy, which stood at an annual £430,000 a decade ago, reduced from last year’s £60,000 to £0.

This is mostly due, of course, to the severe reduction, during 14 years of Tory misrule, in the government funding on which local authorities depend. The present generation of Conservative Party politicians seems to regard the arts as something that might open minds and encourage independent thought, and therefore to be stamped on.

On the train from London I’d been reading a depressing piece in the FT about the boom in giant high-tech music arenas — the sort of place where you might go to see Taylor Swift or U2 — being built around the country, paralleled by a crisis affecting small-scale venues, almost one in six of which closed or stopped scheduling music during 2023. That made a first visit to Peggy’s Skylight seem even more precious.

* The very nice new album by the guitarist John Etheridge and his organ trio was recorded live at Peggy’s Skylight. It’s called Blue Spirits, it’s on the DYAD label and appropriately enough it concludes with Etheridge’s solo treatment of a favourite Mingus tune, “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat”. Forthcoming attractions at the club include the saxophonist Tony Kofi and the trombonist Dennis Rollins. Full programme: peggysskylight.co.uk

If your name isn’t Van Morrison, it takes some kind of courage to tackle Astral Weeks, one of the sacred texts of the late ’60s. No one has ever really explained how the singer, his American musicians and Larry Fallon, the arranger and conductor, and his producer, Lewis Merenstein, came up with the unique blend of idioms that make the album so distinctive. Jazz, folk, rock and blues are all in there, but so thoroughly metabolised that the eight songs create, for the length of a long-playing record, an idiom of their own. In his lyrics, too, Morrison plunged head-on into a new world of poetic spirituality.

If your name isn’t Van Morrison, it takes some kind of courage to tackle Astral Weeks, one of the sacred texts of the late ’60s. No one has ever really explained how the singer, his American musicians and Larry Fallon, the arranger and conductor, and his producer, Lewis Merenstein, came up with the unique blend of idioms that make the album so distinctive. Jazz, folk, rock and blues are all in there, but so thoroughly metabolised that the eight songs create, for the length of a long-playing record, an idiom of their own. In his lyrics, too, Morrison plunged head-on into a new world of poetic spirituality.