I’ve been listening to Rhiannon Giddens’ new solo album, Tomorrow Is My Turn, while reading Mick Houghton’s just-published biography of Sandy Denny, I’ve Always Kept a Unicorn. Not at the same time, you understand, but it’s an interesting and salutary juxtaposition.

I’ve been listening to Rhiannon Giddens’ new solo album, Tomorrow Is My Turn, while reading Mick Houghton’s just-published biography of Sandy Denny, I’ve Always Kept a Unicorn. Not at the same time, you understand, but it’s an interesting and salutary juxtaposition.

Tomorrow Is My Turn is almost scary in the perfection of its settings for Giddens’ treatment of blues, folk, country and gospel songs. As a producer of this kind of material, T Bone Burnett offers a guarantee of empathy: a mandolin here, a fiddle there, a banjo where needed, a touch of horns, a subtle wash of strings, all applied with the greatest sensitivity to an exquisite choice of material. It’s one of the year’s essential purchases, a huge step forward for a singer whose work with the Carolina Chocolate Drops had already established her credentials as an interpreter of roots music. She’s a very fine singer, and she deserves this treatment. You find yourself nodding your head in admiration as she copes so elegantly with the various idioms (even French chanson: check the poised understatement of her version of the Charles Aznavour song that gives the album its title).

Sandy Denny, however, was not merely a fine singer: she was a great one. Not only were her tone and phrasing lovely and distinctive, but she sang from the inside of a song and she had the gift of slowing your heartbeat to match the pulse of her music. What she didn’t possess were the attributes that seem to be propelling Giddens to a higher plane: a powerful sense of focus, a rock-solid self-confidence, and the right team around her at the right time.

I knew Sandy a little, and even 37 years after her death I found reading I’ve Always Kept a Unicorn an extremely distressing experience. Mick Houghton is not a dramatic writer, but he doesn’t need to be: he just needs to stitch together, with quiet diligence and the aid of fresh testimony from many of her surviving friends and colleagues, the story of how Alexandra Elene MacLean Denny, born in Wimbledon in 1947, achieved recognition without managing to build the sort of career that everyone expected her to have, and then fell so fast and so conclusively that she was dead at 31.

Two linked episodes — the aftermath of Fairport Convention’s motorway tragedy and the saga of Fotheringay — stand out as pivotal. One night in May 1969 the van carrying members of Fairport Convention back to London from a gig in Birmingham crashed down an embankment on the M1, killing Martin Lamble, their drummer, and Jeannie Franklyn, the girlfriend of Richard Thompson, their lead guitarist. The traumatised band recruited a new drummer, Dave Mattacks, and a fiddler, Dave Swarbrick, and threw themselves into a different kind of project: the album Liege and Lief, in which they applied rock-band techniques to traditional material. It was released in December of that year, and its instant critical acceptance as a benchmark in the evolution of folk-rock diverted them from the musical path they would surely have followed had the accident never happened and the fast-evolving songwriting of Sandy and Richard remained the core of their activity.

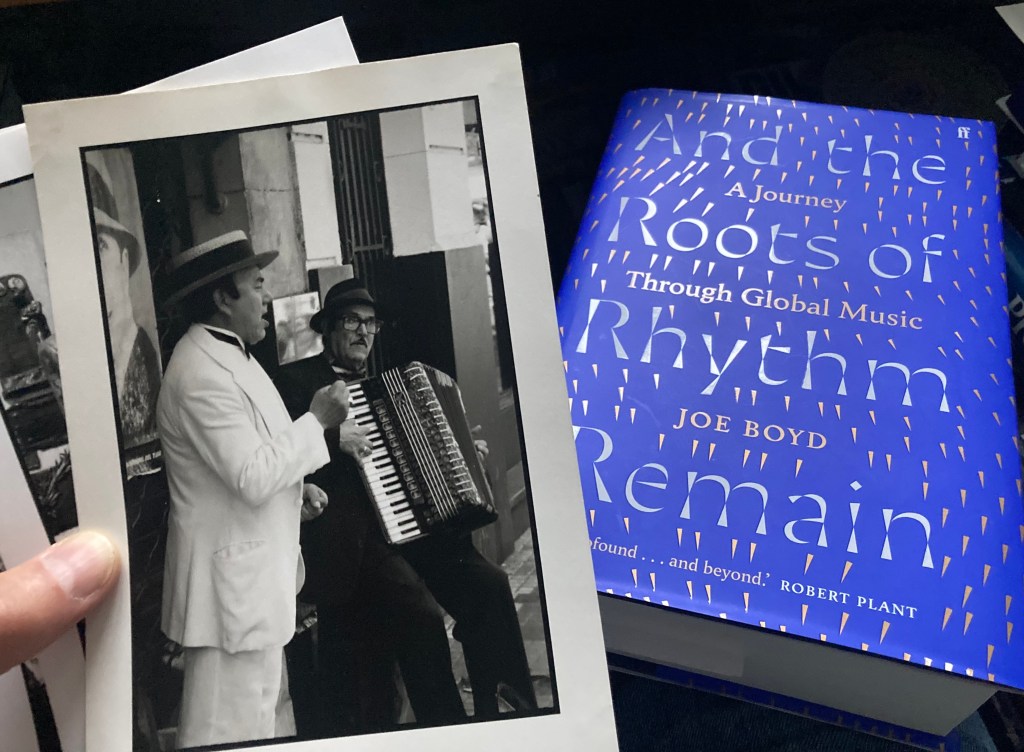

Eventually the pair left in frustration, both keen to stretch their wings. Sandy put together the five-piece Fotheringay in 1970 with her new boyfriend, the Australian singer/guitarist Trevor Lucas. Joe Boyd, who had mentored and produced the Fairports, firmly believed that Sandy’s future was as a solo artist, not as a member of another group — particularly not one organised, as she insisted, along strictly democratic and non-hierarchical lines. He distrusted the charismatic but headstrong Lucas, and he was appalled by the way the record company’s large advance — originally predicated on a solo album — was being blown on such things as an oversized PA system and a Bentley in which they made their way to gigs.

But although Fotheringay’s first album, and their uncompleted second effort, may have been recorded under Boyd’s disapproving gaze, out of those sessions came the finest moment of Sandy’s career. Within the highly original and starkly dramatic arrangement of “Banks of the Nile”, a traditional ballad telling the story of the reaction of a young girl to the imminent departure of her soldier lover, Sandy seems to summon centuries of English history. As the singer Dick Gaughan said on the subject, in an eloquent note in the booklet accompanying A Boxful of Treasures, the five-CD anthology released by Fledg’ling Records in 2004: “The raw, aching agony which she brings to her reading of it makes it impossible not to feel the fear and grief of the young woman at the separation from her loved one and the uncertainty of his return from the horrors of war . . . It is the supreme example of the craft of interpreting traditional song and is the standard every singer should be aiming for.”

Sandy didn’t write “Banks of the Nile”, but she did write “Who Knows Where the Time Goes”, “Late November”, “John the Gun”, “It’ll Take a Long Time” and other songs that showed her gift for taking a sudden but invariably graceful left turn with a melody or finessing an unexpected chord change with perfect logic, and for lyrics that often contained affectionate but clear-eyed portraits of friends and fellow musicians (Anne Briggs in “The Pond and the Stream”, for example, or Richard Thompson in “Nothing More”). But “Banks of the Nile” indicates most clearly what might have been, had a combination of internal and external pressures not provoked the disintegration of Fotheringay after less than a year, thus denying her the chance to remain a member of a sympathetic and settled unit whose collective musical ambition matched her own.

Chronic insecurities were beginning to hinder her career, particularly after the rupture with Boyd, which removed a provider of support and decisiveness. The biggest blow to Fotheringay was dealt by the Royal Albert Hall concert of October 1970. Disastrously, they invited Elton John to open the show, at the very moment when his career was taking off. He hadn’t yet grown into his full on-stage flamboyance, but his performance was powerful enough to put his hosts in the shade. When they came out after the intermission, it was somehow like the colour on a TV set had been suddenly turned off — and the audience, which had come to acclaim Sandy and her band, found themselves present at an epic anti-climax. Three months later, demoralised by that event and by the unsatisfactory sessions for their projected second album, the band broke up — thanks largely to a simple misunderstanding between Sandy and Joe Boyd over the terms on which he would produce her first solo effort.

In fact Boyd never produced her in the studio again, and the four solo albums released between 1971 and 1977 chronicle a diminishing ability to identify and present the essence of who she really was. The overproduced (by Lucas) cover version of Elton John’s “Candle in the Wind” on the final album, Rendezvous, represented some sort of nadir. The record company — Island — did its best, which too often turned out to be not so good. She found herself agreeing to be photographed by David Bailey, to be dressed up in a 1930s costume, and to be airbrushed and wind-machined in an effort to create an image more superficially glamorous than that represented by her own true self. As Island grew too quickly and had its head turned by success, her career became, to some extent, collateral damage.

When she was voted Britain’s top female singer by the readers of the Melody Maker not once but twice, in 1970 and 1971, it was assumed that commercial success would take care of itself. But after Boyd, she didn’t get much constructive help — for which, now, I must partially blame myself, since I was running Island’s A&R department between 1973 and 1976. But the artists inherited from Boyd’s Witchseason stable were somehow thought to be a law unto themselves in terms of musical direction, and although Sandy was loved within the company for her warmth of her personality as well as for her artistry, she was not biddable. Nor, in those days, were real artists supposed to be.

Houghton doesn’t slow up the narrative by spending much time describing the music, but he does make some discreetly perceptive observations. He remarks that Sandy’s first solo release, The North Star Grassman and the Ravens, is “the only album on which Sandy steadfastly stands her ground — usually by the seashore or the riverbank — and invites her audience to come to her.” And he writes of Trevor Lucas, five years later, working on the production of the ill-starred Rendezvous, “doing such protracted overdubs that it was almost as if he was subconsciously trying to bury the sentiments of the songs.”

Although delving deep into her turbulent love-match with Lucas and the increasing dependence on drugs and alcohol that accompanied her decline, he treads lightly when it comes to other, deeper-lying factors that might be held partially responsible for her unhappiness, such as an enduring fretfulness about her looks (particularly her weight) and an apparent history of abortions and miscarriages. Some readers may feel that the significance of these matters looms larger than the author allows himself to suggest. Eventually, in 1977, she would have a child with Lucas, a girl whom the father found it necessary to kidnap and take off to Australia less than a year later, as Sandy’s problems worsened. Four days after their unannounced departure she was found unconscious at the foot of the stairs at a friend’s flat in Barnes, and died in hospital a further four days later.

It’s a shock to realise that someone you knew has now been dead for longer than they were alive. Had she lived, she would have turned 68 a few weeks ago. Perhaps in that time she’d have encountered another manager, producer or A&R person capable of earning her trust, focusing her talent, nurturing the elements that made her unique, and presenting them to the world in the right package — the kind of package that Rhiannon Giddens seems to have been granted in 2015. Who knows how much great music was left in her? I like to think of Sandy coaxing Anne Briggs out of seclusion and inviting Kate Rusby to join them both on stage.

Houghton’s scrupulously fair account of her life makes it clear that she could be difficult and destructive, but allows those who knew her well to remember another side. The drummer Bruce Rowland — who had replaced Dave Mattacks in the Fairports by the time she recorded a last album, Rising for the Moon, with the band in 1975 — touchingly calls her “endlessly forgivable”. Her old folk-club mate Ralph McTell tells Houghton: “She would provoke — push people to the very limit at times, which sounds like she was a nasty person, but she wasn’t. People would take it because they loved her. I don’t know anyone who didn’t love her.” And you didn’t have to know her to love her. You only had to listen to “Banks of the Nile”.

* I’ve Always Kept a Unicorn is published by Faber & Faber. Tomorrow Is My Turn is released on the Nonesuch label.