Back to Berlin

“A lot of people have died recently,” Otomo Yoshihide remarked to his Berlin audience on Sunday night, halfway through a set by his 16-piece Special Big Band. “This is for them.” The band’s marimba player, Aikawa Hitomi, began to trace out some quiet, limpid phrases, with a sound like pebbles dropping in a pond. One by one, her colleagues joined in. I don’t really know how to explain what was happening, whether or not it was a written composition or completely improvised, but each player added a layer of sadness to the piece until it gradually, and completely without ostentation, reached a critical mass of emotion.

It was amazing. The non-specific nature of Yoshihide’s introduction allowed the listeners — and the musicians, I guess — to direct their mourning wherever they wished. And having created something so sombre and profound, Yoshihide didn’t take the bandleader’s easy option by then lifting the mood with one of the absurdly entertaining rave-ups in which his band specialises, and with which they would eventually send the audience home smiling fit to burst. Instead his accordionist, Okuchi Shunsuke, squeezed out the gentle melody of “Années de Solitude”, a graceful composition by the great Astor Piazzolla. Soon the lonely accordion was joined the baritone saxophone of Yoshida Nonoko, before the other horns entered in a rich arrangement ending with hymn-like cadences.

After that, it was time to change the mood in a set that contained an unusually large proportion of the gamut of human emotions, from cheesy film and TV themes and a perky “I Say a Little Prayer” through a pretty version of Eric Dolphy’s “Something Sweet, Something Tender” and a suitably stirring reading of Charlie Haden’s “Song for Che”. The encore was a completely bonkers piece of Japanese pop music featuring the all-action singing and dancing of three of the group’s women — Hitomi, the electronics player Sachiko M and the saxophonist Inoue Nashie — with a kind of rap from Yoshihide.

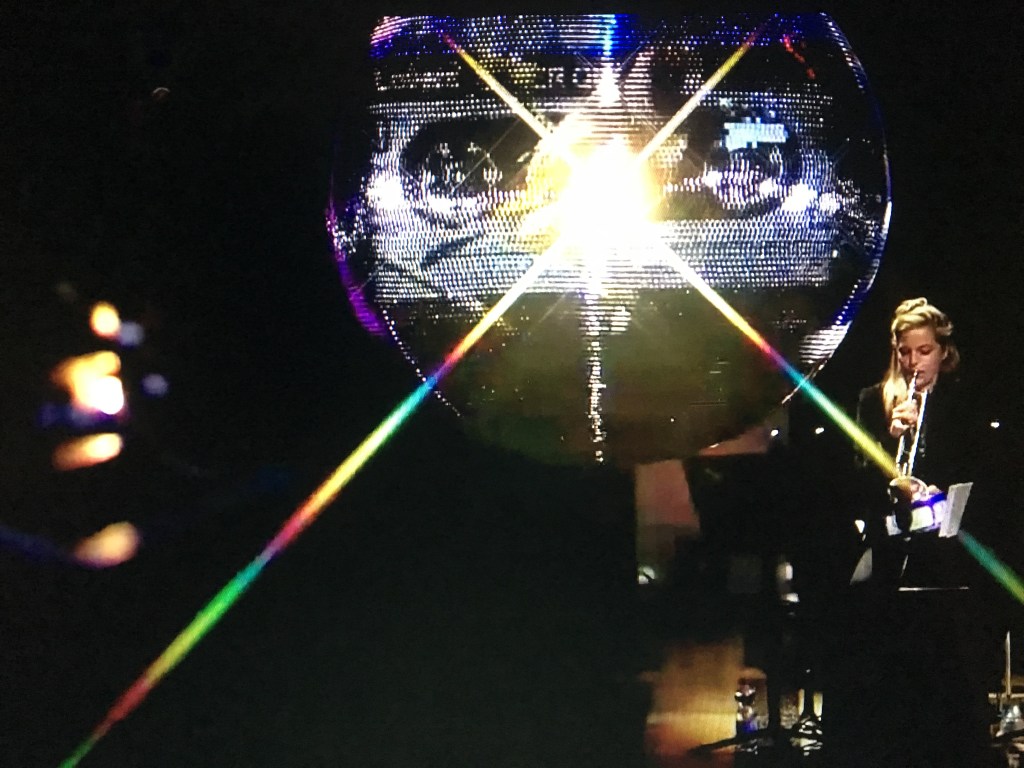

For the closing performance of the 2024 JazzFest Berlin, Yoshihide’s ensemble was the perfect choice. Twenty four hours after the Sun Ra Arkestra had occupied the same stage in their tinsel and cooking-foil Afrofuturist costumes, recessing from the stage one by one with a chanted recommendation for Outer Spaceways Incorporated, the men and women of the Japanese band came dressed like refugees from a Comme des Garçons sample sale. Were they from the West, Felliniesque would be one obvious way of describing their presentation. With two drummers, a tuba and a very emphatic bass guitarist, and with the leader’s guitar sometimes throwing in some of the noise elements for which he is well known, they made me think of what might happen if you merged the Willem Breuker Kollektiev with the Glitter Band, with Carla Bley providing the arrangements.

One amusing thing they did in the up-tempo pieces was to have each member leap up to give cues and perhaps conduct a few bars before resuming their places: a kind of daisy-chain of instructions and cheer-leading. It made me think of something I’d seen that morning on stage at the Jazz Institut, where the festival’s Community Sunday, centred on the multicultural Moabit district of Berlin, began with a concert featuring children. While a young piano trio played, a group of kids, perhaps six to 10 years old, stood in front of them, giving the sort of signals — faster! slower! stop! start! — familiar from the techniques of conduction.

It was a good game, everyone enjoyed it, and it made me wonder whether, a few decades ago, someone had tried something similar in Japan, laying the foundations for Otomo Yoshihide’s Special Big Band. Almost certainly not, but there was the same sense of play at work, as it were. And if you give that opportunity to a bunch of kids, there must be a chance that it will open up a world for some of them.

The Moabit adventure continued with a mass walk through the streets, audience and musicians stopping off at various points for pop-up musical events. It ended in a church, where Alexander Hawkins played the organ and members of the Yoshihide band and the Swedish bassist Vilhelm Bromander’s Unfolding Orchestra took part, along with a young people’s choir and local musicians with various cultural backgrounds. The special project of Nadin Deventer, now seven years into her tenure as the festival’s artistic director, it proved to be a brilliant way to involve a community and its children, and deserves to become a permanent feature of an institution celebrating its 60th birthday.

For me, other highlights of the four days included Joe McPhee reading his poetry with Decoy; the French pianist Sylvie Courvoisier’s new quartet, Poppy Seeds, featuring the vibraphonist Patricia Brennan, the bassist Thomas Morgan and the drummer Dan Weiss, playing compositions of great intricacy with superb deftness; and the trio of two British musicians, the pianist Kit Downes and the drummer Andrew Lisle, and the Berlin-based Argentinian tenor saxophonist Camila Nebbia, entrancing a packed A-Trane with warm gusts of collective improvisation. In the main hall on Saturday night there was also a moving ovation for the pianist Joachim Kühn, who made a speech announcing that, at 80, this appearance with his current trio would be his last at the festival, having made his first in 1966, aged 22.

A festival with an ending, then, in more than one sense, but also full of beginnings and new possibilities, just as the visionary jazz critic and impresario Joachim-Ernst Berendt envisaged 60 years ago when he persuaded the West German government that its slice of Berlin, marooned in the GDR, needed something with which to demonstrate a sense of vibrant modernity to the world, and that thing was jazz. In very different circumstances, it still is.