The last of the Tops

There’s still something distinctly majestic, even monumental, about the run of more than a dozen hits that Eddie and Brian Holland and Lamont Dozier wrote and/or produced between 1964 and 1968 for the Four Tops, whose last surviving original member, Abdul “Duke” Fakir, died this week, aged 88.

It’s a Himalayan range of which the peak, of course, was “Reach Out, I’ll Be There”. I can still remember hearing it for the first time, played by Mike Raven on Radio 390 one evening in 1966, and being transfixed not just by its unprecedented arrangement — the galloping percussion, the piping woodwind, four to the bar on a tambourine, the celestial choir — but by the realisation that someone at Motown had been listening to Bob Dylan. For a fan of both kinds of music, that much was immediately obvious in the urgent repetitive incantation of the melody, so far away from the normal structures of Motown tunes.

The run of hits began in 1964 with “Baby I Need Your Loving”, its swinging rhythm carried by fingerpops on the backbeat — unusual for Motown, although also tried a couple of years later on Martha and the Vandellas’ “No More Tearstained Make Up” — and by James Jamerson’s inventive bass line. It reached the fringes of the Top 10, and remains much loved, but the follow-up, “Without the One You Love”, was too close to it to repeat that success. Listening to it now, I also realise that the bass player on this one must have been someone else; whoever it is, all he does is follow the root note, with none of the octave leaps, passing notes and general fluidity that made Jamerson’s work so distinctive.

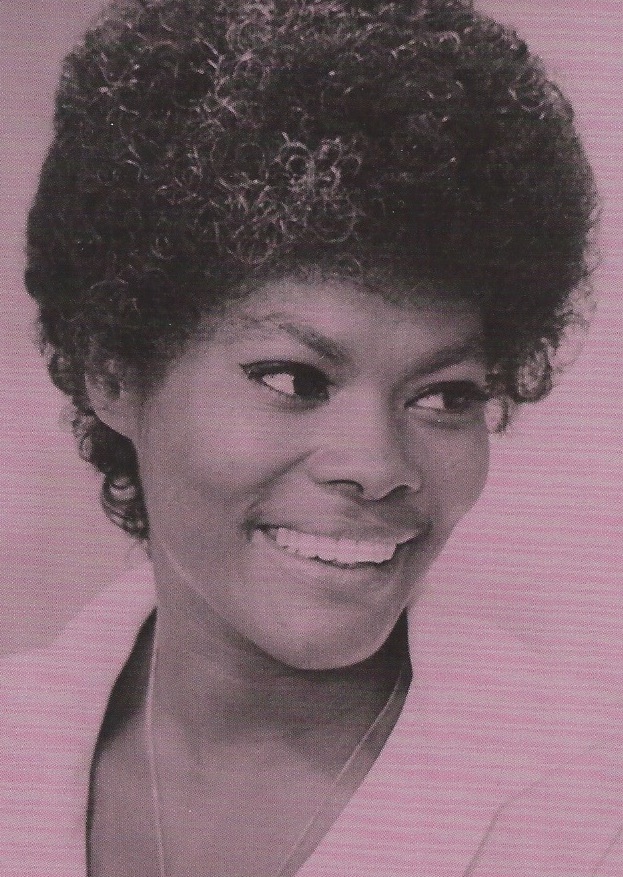

Their third Motown single was a gorgeous anomaly: a heartbroken ballad written and produced not by H-D-H but by William Stevenson, the label’s A&R director at the time, and Ivy Jo Hunter. Jamerson returns here, working in conjunction with open strummed rhythm guitars. And as with its two predecessors, what’s particularly noticeable is the use of the Andantes, a female vocal trio, to add to the Tops’ own background harmonies. Jackie Hicks, Marlene Barrow and the soprano Louvain Demps never had a Motown hit in their own right, but they created a kind of penumbra of emotion that gave this record, and almost all the early Tops hits, a special quality that eludes analysis but goes straight to the inconsolable heart.

For their fourth single, and first No 1, they went back to Holland-Dozier-Holland in the spring of 1965 for “I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar Pie Honey Bunch)”, a record that established a template for bass-driven dance records, Jamerson bouncing off the 4/4 on the snare drum and Jack Ashford’s vibes. It was never a favourite of mine, unlike its slightly less successful successor, “It’s the Same Old Song”, which follows the formula but relies less on the bass line and has a lyric you could dance to.

“Something About You” emphasised the pounding beat, forfeiting some of the poetry rediscovered in “Shake Me, Wake Me (When It’s Over)”, and the move towards a funkier sound culminated in the return of Ivy Jo Hunter, co-writing “Loving You Is Sweeter Than Ever” with Stevie Wonder and producing a magnificent track based on chords whose voicings descend with a dark and thrilling inevitability, paced in a deliberate rhythm by the patented combination of tambourine, snare drum and chopped guitar on 2 and 4.

Then came the great run of “Reach Out, I’ll Be There”, “Standing in the Shadows of Love” and “Bernadette”, a trilogy united by the anguish of Levi Stubbs’ lead vocals and the exuberant imagination at work in the arrangements. Jamerson is at his towering best on “Standing in the Shadows”, where Eddie “Bongo” Brown’s congas grab the spotlight in four-bar breaks that foreshadow the tactics of disco remixers a decade later. The third part of the trilogy is remembered for a sudden silence broken by Stubbs’ cry of utter desperation — “BERNADETTE!” — but the female voices have already painted the backdrop, reaching up to touch the heavens.

After that came “7 Rooms of Gloom”, a track that almost turned the trilogy into a tetrad, its opening a masterpiece of suspense before drums and bass enter in a flurry, with a hint of harpsichord in the background. Then “You Keep Running Away”, notable for Jamerson’s hyperactivity and the two sets of syncopated convulsions that form a bridge between sections, and its B-side, the tearstained gospel-doowop fusion of “If You Don’t Want My Love”, with the harpsichord marking out the chord cycle.

We’re in 1968 now, and the two lush covers of the Left Banke’s “Walk Away Renée” and Tim Hardin’s “If I Were a Carpenter” were unexpected and beautifully soulful. But by the end of the year H-D-H were on their way out of Motown, leaving the Tops with one last masterpiece: “I’m in a Different World”, a gear-change in synch with (and perhaps a response to) Norman Whitfield’s increasingly adventurous productions for the Temptations. Dramatic changes of density with layers of guitars, a swoosh of strings, a bed of percussion: bass drum, congas, and that hi-hat, a single stroke hissing midway through every bar: “one-and-two-AND-three…”

Now Duke Fakir, whose tenor led the group’s background harmonies, has gone to joined his Detroit friends Lawrence Payton, who arranged those harmonies, Renaldo “Obie” Benson and Stubbs. What a run they had, and what a range of peaks they left, each one still catching the sun from a different angle.