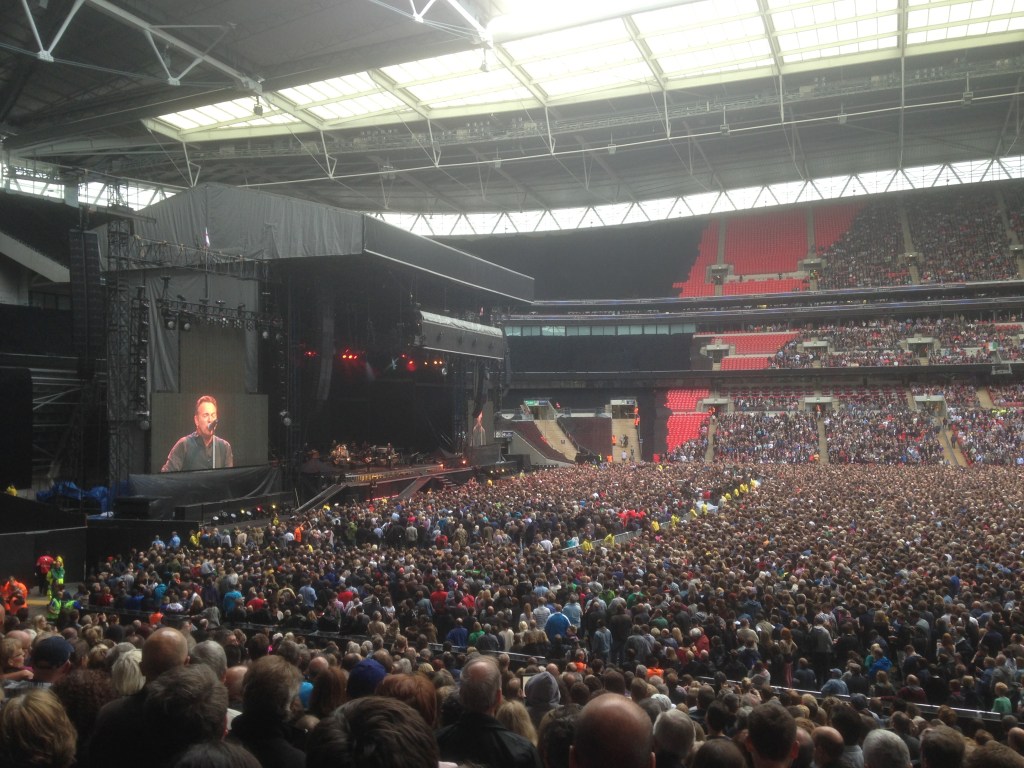

It’s 10 years since the veteran countercultural insurrectionist Mick Farren died. In 1976, in a celebrated polemic for the NME headlined “The Titanic sails at dawn”, he asked: “Has rock and roll become another mindless consumer product that plays footsie with jet set and royalty, while the kids who make up its roots and energy queue up in the rain to watch it from 200 yards away?” I thought of his words while watching — from a range of almost exactly 200 yards, as it happened, albeit on a warm, dry afternoon — Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band giving the first of their two concerts in Hyde Park.

Farren wrote his piece only seven years after the Rolling Stones had played a free concert in Hyde Park to an audience of perhaps a quarter of a million (although I’ve always questioned that figure): a significant event in the history of both the band and the Sixties youth culture of which it was a part. All you had to do was turn up and find yourself a space on the grass. There were no merchandise stalls, because there was no merchandise. If you wanted anything to eat, drink or smoke, you had to bring it with you.

By contrast, Springsteen’s gigs (and others in the British Summer Time series) were sponsored by American Express. To secure a couple of tickets, even those very far away from the privileged enclosures housing the jet set (and perhaps even royalty), you needed to spend a few hundred quid. In the days leading up to the event, there were messages via a special app telling you what to expect and what you could and couldn’t do, with a map of the site, a list of prohibited items (including food and drink), and so on. And it all worked fine. Pleasant attendants, a variety of refreshment outlets and the provision of adequate toilet facilities made it a civilised experience. The weather was warm but not too hot, and the setting sun provided the golden light that enhances any performance.

Once upon a time Springsteen made concert halls feel like clubs. Then he made stadiums feel like concert halls. At 73 he still performs for three hours with impressive vigour and generosity of spirit (he gives the band a mid-set break rather than taking one himself), but nowadays his big gigs feel like big gigs. That’s the price, I guess, of having such a massive following. But although I liked hearing “Darlington County” and “Mary’s Place” and “Badlands” and “Wrecking Ball”, and enjoyed his decent stab at the Commodores’ “Nightshift”, a lot of the set sounded coarsened, which was not how it used to be. Maybe the band is now so big — all those horns and voices — that the music has lost the agility which was such a vital part of its early charm.

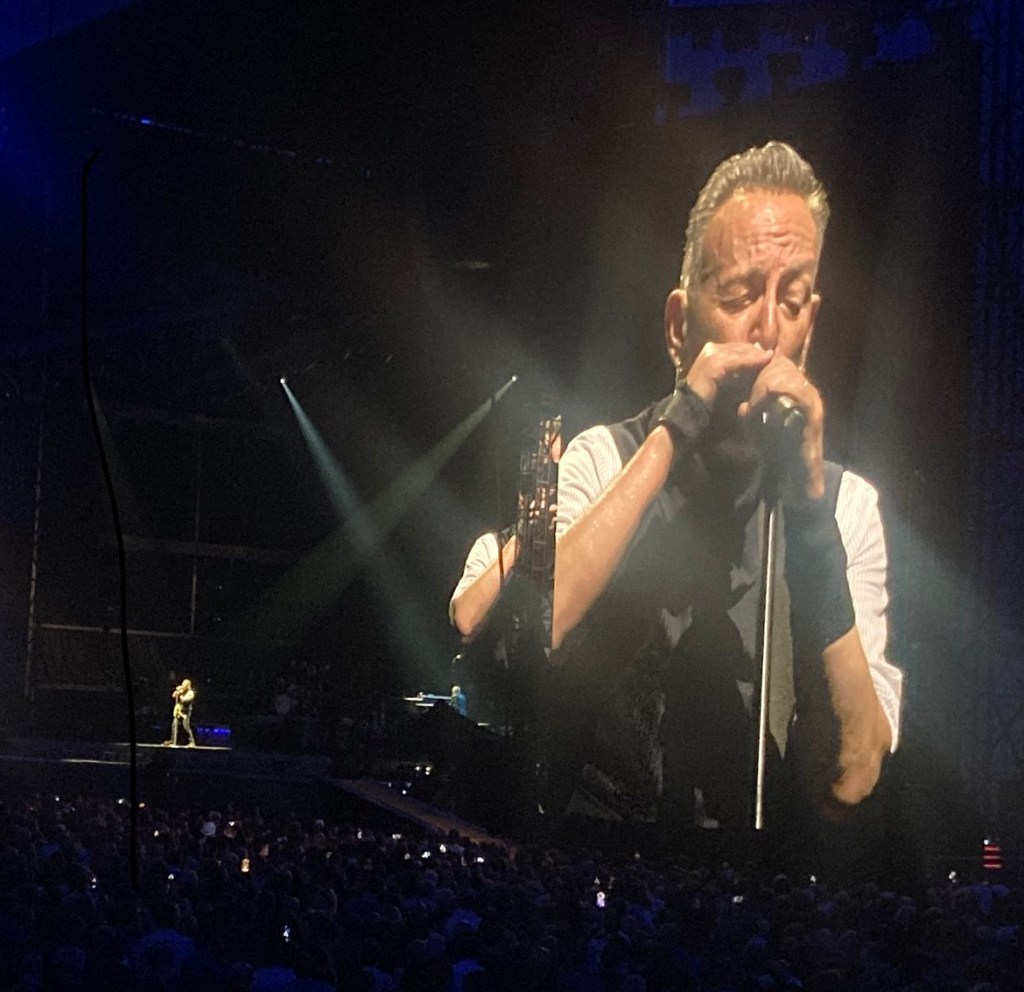

And, of course, from 200 yards, each figure on stage was about a quarter the size of a matchstick. So you watched it all on the big screens. Which, inevitably, were not quite synched with sound travelling such a distance to where I was standing. That was about halfway back in a crowd of 62,000, some of whom said afterwards that it was the best Springsteen show they’d ever seen. In the Guardian, Jonathan Freedland wrote an affecting piece about his reaction to the concert’s valedictory tone and its message for a generation now growing old.

I don’t begrudge anyone their enjoyment in Hyde Park. I’ve seen Springsteen at other times and in other places when the shows he delivered were as good as anything of their kind could possible be. But when I think about the corporate infrastructure of the Hyde Park concerts, and about the row over “dynamic pricing” in the US, and about the stories of what people are having to go through (and spend, of course) to see Taylor Swift on her forthcoming tour, I think Mick Farren’s point was so well made that its meaning has only grown louder over the years.

When he wrote that piece, punk rock was coming down the track. For a while that movement seemed to destabilise the commercial edifice built up around the music. Then the music industry found ways to reassert its authority, to globalise its product while building an impenetrable wall around it. Whatever the instincts and virtues of Springsteen, Swift and others, however immaculate and sincere, their gigantic tours are now an expression of that authority.

I’m probably sounding naive, because in a sense it’s nothing new. At the time of their free concert in Hyde Park, the Stones were managed by Allen Klein, the American hustler whose involvement was emphatically not motivated by countercultural concerns. Mick Farren also wrote books about Elvis Presley, and he knew perfectly well that Colonel Tom Parker didn’t care about Elvis’s audience or the culture they represented. He cared about making a buck.