Danny Thompson 1939-2025

The first time I saw Danny Thompson, he was playing with Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated at the Dungeon Club in Nottingham. This would have been the spring of 1965. I must have liked his playing a lot because I got him to autograph a paperback copy of Nat Hentoff’s The Jazz Life that I happened to be carrying that night.

A couple of years later I saw him with the Pentangle, a band that to my ears never equalled the sum of its parts. It was his long-standing partnership with John Martyn that brought out his best, whether racing alongside the effects-driven guitar on “I’d Rather Be the Devil” or adding a darkly poetic arco line to “Spencer the Rover”.

Danny, whose death at the age of 86 was announced this week, was a member of a generation of great double bassists who emerged in and around the British jazz scene in the ’60s. If you wanted to line them up in some kind of taxonomy of interests and instincts across a spectrum of the music with which they were associated, starting with folk and proceeding to contemporary classical, it would probably go something like this: Danny, Ron Matthewson, Dave Green, Jeff Clyne, Harry Miller, Dave Holland, Chris Laurence, Barry Guy. Obviously that’s not everyone.

Danny was the Charlie Haden of British bassists, his playing warm and deep-toned, as rooted in folk modes as Haden was in bluegrass music, but just as capable of dealing with the most advanced and abstract forms.

Maybe the best way to celebrate his life is to listen to Whatever, the album he recorded for Joe Boyd’s Hannibal label in 1987. It finds him with a trio completed by two relatively unsung heroes of the scene, the wonderful Tony Roberts on assorted reeds, flutes and whistles and the terrific guitarist Bernie Holland.

I remember giving it an enthusiastic review in The Times, commending its highly evolved fusion of folk materials and jazz techniques. It’s a little bit like a British version of Jimmy Giuffre’s Train and the River trio, unafraid of the bucolic and the open-hearted.

Most of the pieces are credited as joint compositions but some are arrangements of traditional pieces, such as “Swedish Dance”, which opens with a bass solo rich in disciplined emotion before moving into an ensemble workout on a light-footed tune whose complex rhythms are made to sound as charming as a children’s song. The stately melody of “Lovely Joan” is delivered by Roberts on a set of Northumbrian pipes — mellower than their Scottish or Irish equivalents — before he switches to soprano saxophone for an intricate conversation with Holland’s nimble acoustic picking and Thompson’s firmly grounded bass. Of the originals, “Minor Escapade” adds elements of the classic John Coltrane Quartet to this trio’s distinctive approach.

Not having played it for some years, I’d forgotten what a truly exhilarating album it is. Now it’ll be at the top of the pile for some time to come, adding the sparkle and freshness of its understated virtuosity to the room. RIP, Danny.

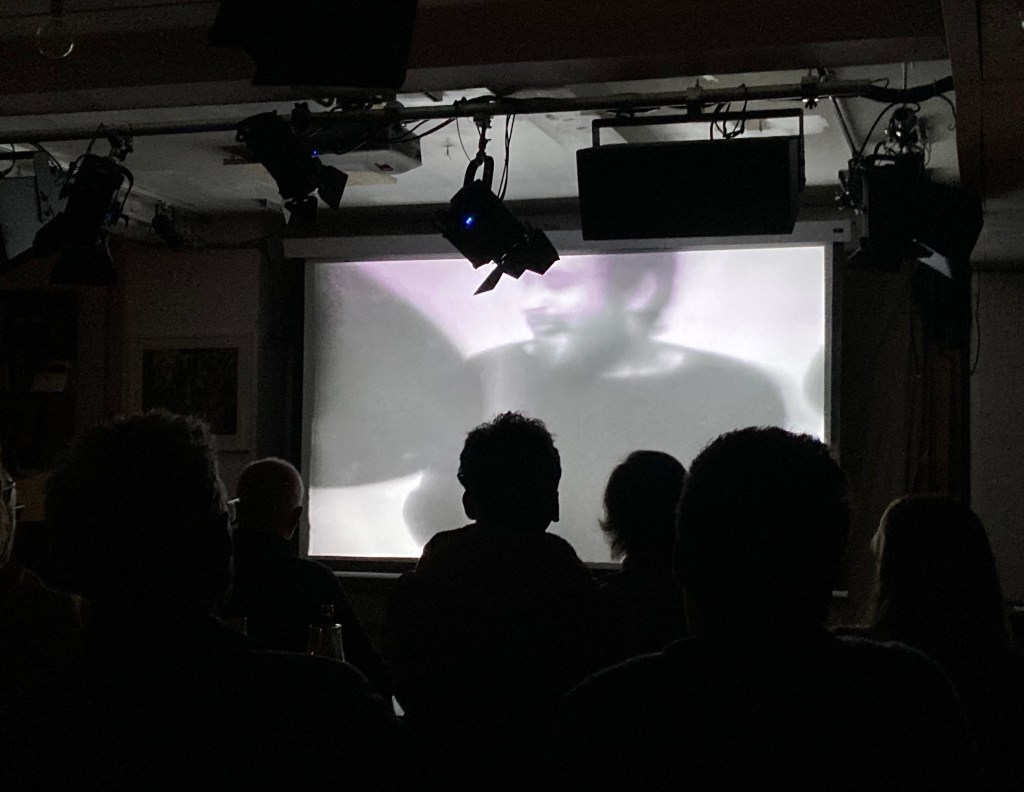

* The photo of Danny Thompson is from the cover of Whatever and was taken by Nick White.