Everybody Loves a Train

About twenty years ago, my friend Charlie Gillett was compiling a series of themed CDs for a Polygram label called Debutante, under the aegis of the former Island A&R head Nick Stewart. Charlie asked me if I’d like to put one together, and if so, what the theme might be. “Trains,” I said, after about ten seconds’ thought, and then I went away to assemble a running order. It took a while, because I enjoyed the process so much.

Sadly, the series came to a sudden end before my contribution could see the light of day. But I’d edited together a disc of how I wanted it to go. I called it Everybody Loves a Train, after the song by Los Lobos. It has all sorts of songs, some of which speak to each other in ways that are obvious and not. I avoided the most obvious candidates, even when they perfectly expressed the feeling I was after (James Brown’s “Night Train” and Gladys Knight’s “Midnight Train to Georgia”) and instrumentals, too (see the footnote).

Every now and then I take it out and play it, as I did this week, with a sense of regret that it never reached fulfilment. Here it is, with a gentle warning: not all these trains are bound for glory. Remember, as Paul Simon observes, “Everybody loves the sound of a train in the distance / Everybody thinks it’s true.”

- Unknown: “Calling Trains” (From Railroad Songs and Ballads, Rounder 1997) Forty-odd seconds of an unidentified former New Orleans station announcer, recorded at Parchman Farm, the Mississippi state penitentiary, in 1936, calling from memory the itinerary of the Illinois Central’s “Panama Limited” from New Orleans to Chicago: “…Ponchatoula, Hammond, Amite, Independence… Sardis, Memphis, Dyersburg, Fulton, Cairo, Carbondale…” American poetry.

- Rufus Thomas: “The Memphis Train” (Stax single, 1968) Co-written by Rufus with Mack Rice and Willie Sparks. Produced by Steve Cropper. Firebox stoked by Al Jackson Jr.

- Los Lobos: “Everybody Loves a Train” (from Colossal Head, 1996) “Steel whistle blowin’ a crazy sound / Jump on a car when she comes around.” Steve Berlin on baritone saxophone.

- Bob Dylan: “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry” (from Highway 61 Revisited, 1965) “Don’t the brakeman look good, mama, flaggin’ down the Double E?”

- Joe Ely: “Boxcars” (from Honky Tonk Masquerade, 1978) A Butch Hancock song. Ponty Bone on accordion, Lloyd Maines on steel guitar.

- Counting Crows: “Ghost Train” (from August and Everything After, 1993) “She buys a ticket ’cause it’s cold where she comes from / She climbs aboard because she’s scared of getting older in the snow…”

- Rickie Lee Jones: “Night Train” (from Rickie Lee Jones, 1979) It was a plane she took from Chicago to LA to begin her new life in 1969, and an old yellow Chevy Vega she was driving before she cashed the 50K advance from Warner Bros ten years later. But, you know, trains.

- The Count Bishops: “Train, Train” (Chiswick 45, 1976) London rockabilly/pub rock/proto-punk. Written by guitarist/singer Xenon De Fleur, who died a couple of years later in a car crash, aged 28, on his way home from a gig at the Nashville Rooms. Note that comma. I like a punctuated title.

- Julien Clerc: “Le prochain train” (from Julien, 1997) My favourite modern chansonnier. Lyric by Laurent Chalumeau.

- Blind Willie McTell: “Broke Down Engine Blues” (Vocalion 78, 1931) Born blind in one eye, lost the sight in the other in childhood. Maybe he saw trains in time to carry their image with him as he travelled around Georgia with his 12-string guitar.

- Laura Nyro: “Been on a Train” (from Christmas and the Beads of Sweat, 1970) One song she didn’t do live, as far as I can tell. Too raw, probably.

- Chuck Berry: “The Downbound Train” (Chess B-side, 1956) When George Thorogood covered this song, he renamed it “Hellbound Train”. He didn’t need to do that. Chuck had already got there.

- Bruce Springsteen: “Downbound Train” (from Born in the USA, 1984) “The room was dark, the bed was empty / Then I heard that long whistle whine…”

- Dillard & Clark: “Train Leaves Here This Morning” (from The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark, 1968) Written by Gene Clark and Bernie Leadon: “1320 North Columbus was the address that I’d written on my sleeve / I don’t know just what she wanted, might have been that it was getting time to leave…”

- Little Feat: “Two Trains” (from Dixie Chicken, 1973) In which Lowell George extends the metaphor of Muddy Waters’ “Still a Fool (Two Trains Running)”: “Two trains runnin’ on that line / One train’s for me and the other’s a friend of mine…”

- B. B. King: “Hold That Train” (45, 1961) “Oh don’t stop this train, conductor, ’til Mississippi is out of sight / Well, I’m going to California, where I know my baby will treat me right”

- Paul Simon: “Train in the Distance” (from Hearts and Bones, 1983) Richard Tee on Fender Rhodes. “What is the point of this story? / What information pertains? / The thought that life could be better / Is woven indelibly into our hearts and our brains.”

- Vince Gill: “Jenny Dreams of Trains” (from High Lonesome Sound, 1996) Written by Gill with Guy Clark. Fiddle solo by Jeff Guernsey. Find me something more beautiful than this, if you can.

- Muddy Waters: “All Aboard” (Chess B-side, 1956) Duelling harmonicas: James Cotton on train whistle effects, Little Walter on chromatic.

- Darden Smith: “Midnight Train” (from Trouble No More, 1990) “And the years go by like the smoke and cinders, disappear from where they came…”

- The Blue Nile: “From a Late Night Train” (from Hats, 1989) For Paul Buchanan, the compartment becomes a confessional.

- Tom Waits: “Downtown Train” (from Rain Dogs, 1985) “All my dreams, they fall like rain / Oh baby, on a downtown train.” A New York song.

Closing music: Pat Metheny’s “Last Train Home” (from Still Life (Talking), 1987) to accompany the photo of the Birmingham Special crossing Bridge No 201 near Radford, Virginia in 1957 — taken, of course, by the great O. Winston Link. Other appropriate instrumentals: Booker T & the MGs’ “Big Train” (from Soul Dressing, 1962, a barely rewritten “My Babe”) and Big John Patton’s “The Silver Meter Pts 1 & 2” (Blue Note 45, 1963, a tune by the drummer Ben Dixon whose title is a misspelling of the Silver Meteor, a sleeper service running from New York to Miami).

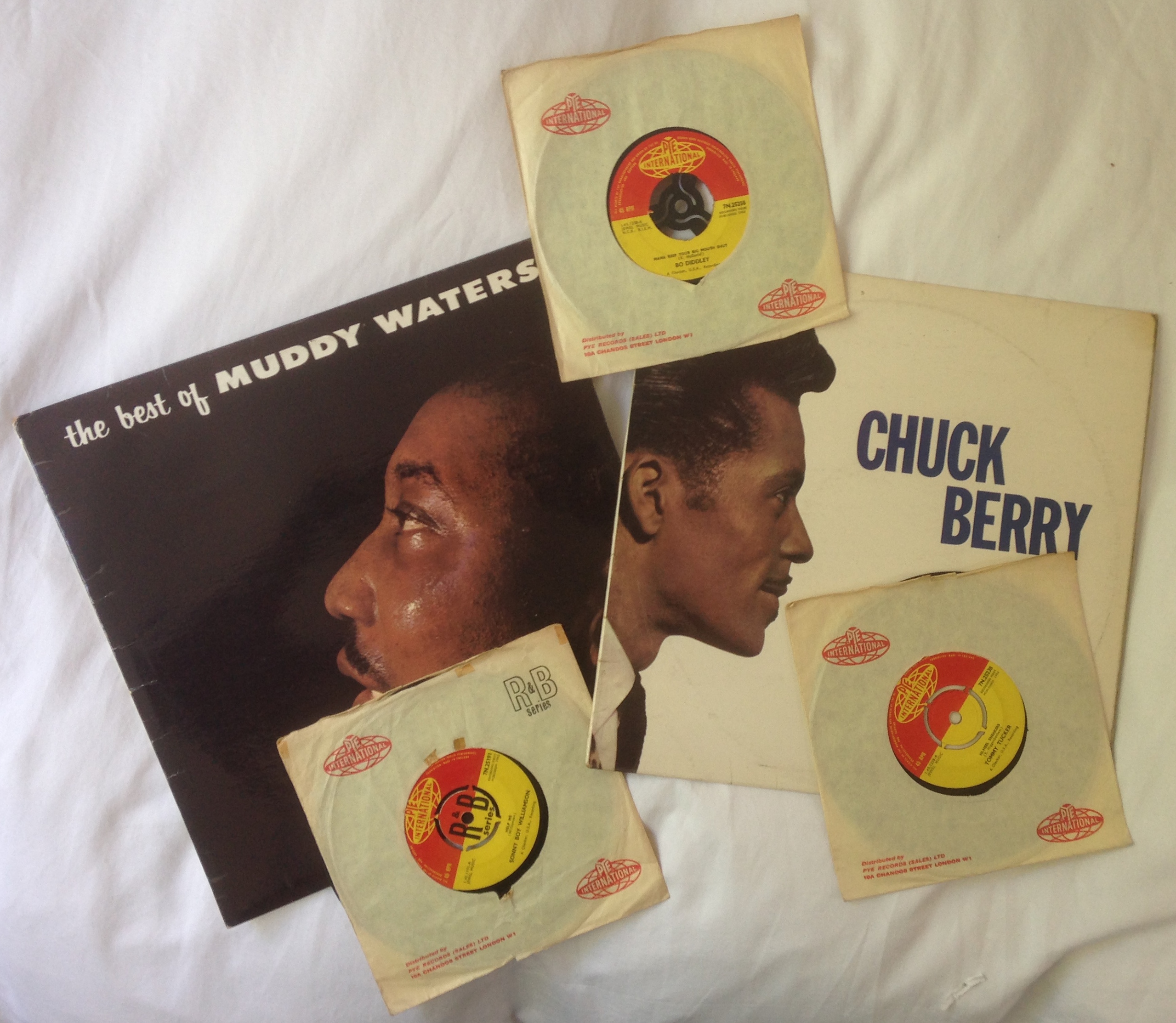

Wilko Johnson’s new autobiography, Don’t You Leave Me Here, received an eloquent recommendation from Mark Ellen in the Sunday Times at the weekend. To coincide with its publication, Universal’s Spectrum imprint is issuing a 40-track double CD set compiled by the former Dr Feelgood guitarist called The First Time I Met the Blues: Essential Chess Masters. Its appearance prompted me to dig out the records you see above: three 45s from my all-time Top 100 box, plus two magnificent albums, all licensed for release in the UK on the Pye International label in the early ’60s.

Wilko Johnson’s new autobiography, Don’t You Leave Me Here, received an eloquent recommendation from Mark Ellen in the Sunday Times at the weekend. To coincide with its publication, Universal’s Spectrum imprint is issuing a 40-track double CD set compiled by the former Dr Feelgood guitarist called The First Time I Met the Blues: Essential Chess Masters. Its appearance prompted me to dig out the records you see above: three 45s from my all-time Top 100 box, plus two magnificent albums, all licensed for release in the UK on the Pye International label in the early ’60s.