Meet the house band

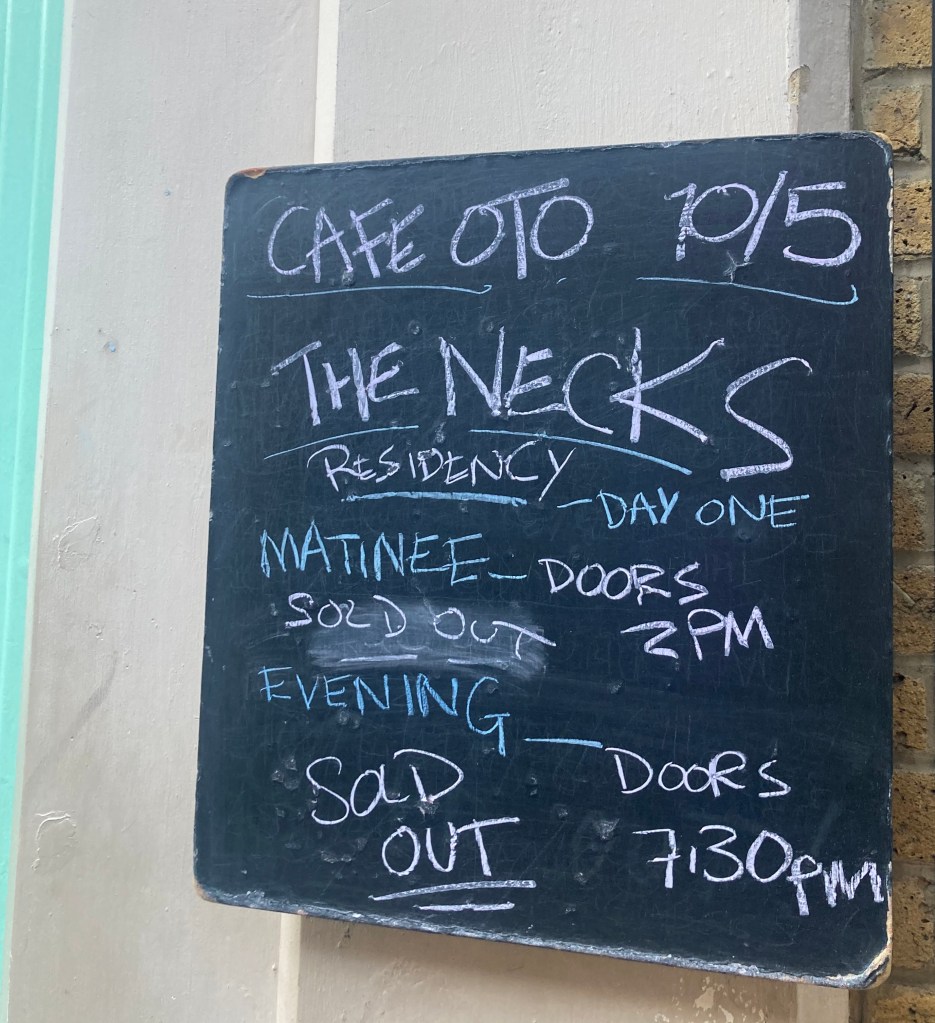

Before the evening show on the first of their two days at Cafe Oto on Saturday, the Necks were announced to the audience as “the house band”. We laughed, and so did they. But it seemed to fit. The Australian improvising trio have played in many London venues, but the little space on Ashwin Street in Dalston seems to suit them best.

Once the house was quiet, they began with Chris Abrahams picking out short melodic phrases in the piano, lightly hammering each note with the two fingers: the index finger of each hand. It was a lovely effect, almost like a santur or cimbalom. The phrases sounded vaguely Moorish, which might seem a bit vague and superficial as a description but is intended to suggest that they felt like fragments of ancient wisdom, conveyed without adornment.

Tony Buck was rubbing two old cymbals on the heads of his snare drum and floor tom-tom. They he began playing a medium fast 1-1-1-1 rhythm with his left hand on the top cymbal of his hi-hat, using a long slender stick. That cymbal stroke formed the basis of his contribution over the next 40 minutes, building in volume and density but retaining a silvery delicacy.

Meanwhile Lloyd Swanton plucked the open D string on his bass with emphasis, letting it ring. That became the tonal centre of the entire collective improvisation, the only fixed point as each of the three explored his own avenue of rhythmic and melodic creation, the symbiosis built up over 30 years enabling them to operate in seeming independence of each other and yet in complete communion. It takes the idea of listening to each other to a different place: listening without listening.

As is usual, but not inevitable, the music gathered power and volume until, by some unspoken intuition, the musicians broke it down, stripping back all the chosen materials until we were returned to the silence.

It’s always tempting to search for analogies and metaphors. Tempting, but unnecessary. Still, on Saturday I thought of the sea breaking on a shore, composed of countless waves and wavelets, all surging and cresting according to their own individual strengths and sub-trajectories, yet responding to a single tidal pulse. It’s an amazing thing to witness in person, when you see how these musicians never even look at each other in performance (Abrahams actually sits side-on, facing offstage) but are linked by something unique.

* The Necks are at Band on the Wall in Manchester tomorrow night (May 13), the Empire, Belfast (14), the Sugar Club, Dublin (15), and thereafter in Switzerland, Portugal, the Netherlands, Croatia, Greece, Poland, Spain, Italy and Belgium: https://shop.thenecks.com/tour-dates

This is the line of ticket-holders waiting to enter Cafe Oto for the Necks’ sold-out lunchtime concert today. It might have seemed an unusual time of day to experience the intensity of free collective improvisation, but the Australian trio’s music tends to work its unique magic at any time of day or night, in any location.

This is the line of ticket-holders waiting to enter Cafe Oto for the Necks’ sold-out lunchtime concert today. It might have seemed an unusual time of day to experience the intensity of free collective improvisation, but the Australian trio’s music tends to work its unique magic at any time of day or night, in any location. Abrahams began the first set with tentative piano figures, joined by Buck’s bass drum and, eventually, Swanton’s arco bass. The pianist tended to hold the initiative throughout, creating arpeggiated variations that slowly surged and receded, gradually building, with the aid of Buck’s thump and rattle and the keening of Swanton’s bow, to a roaring climax — including, from unspecified source among the three, a set of overtones that gave the illusion of the presence of a fourth musician — before tapering down to a perfectly poised landing.

Abrahams began the first set with tentative piano figures, joined by Buck’s bass drum and, eventually, Swanton’s arco bass. The pianist tended to hold the initiative throughout, creating arpeggiated variations that slowly surged and receded, gradually building, with the aid of Buck’s thump and rattle and the keening of Swanton’s bow, to a roaring climax — including, from unspecified source among the three, a set of overtones that gave the illusion of the presence of a fourth musician — before tapering down to a perfectly poised landing.