The vision of Scott LaFaro

Invited to talk about the bassist Scott LaFaro, Ornette Coleman came up with a typically gnomic insight. “Scotty could change the sound of a note just by playing another note,” Coleman told LaFaro’s biographer in 2007. “He’s the only one I’ve ever heard who could do that with a bass.”

There’s a chance to consider what Ornette might have meant while listening to a new three-CD set that compiles work from throughout LaFaro’s sadly abbreviated career, which ended when he was killed in a car crash in 1961, aged 25. Starting with tracks from a 1958 trio album by the pianist Pat Moran, it continues through sessions with the pianists Victor Feldman and Hampton Hawes, the clarinetists Buddy DeFranco and Tony Scott, the trumpeter Booker Little, the arranger Marty Paich, the altoist Herb Geller, the composer John Lewis and the tenorist Stan Getz, as well as Coleman — and, of course, the pianist Bill Evans, with whose celebrated trio he came to fame.

In New York in 1960 Coleman called LaFaro to play alongside his usual bassist, Charlie Haden, in the famous double-quartet session called Free Jazz. Although the two young bassists were friends (LaFaro was then aged 24, Haden 23), it would be hard to imagine a single generation producing two exponents of the instrument with more contrasting styles: Haden darkly thrumming, happy to dig in and walk a basic 4/4, never using two notes where one would do, LaFaro all lightness and velocity and complex phrases executed with quicksilver grace.

When Haden was soon thereafter taken off the scene by drug problems, LaFaro assumed his place in Coleman’s working band and recorded again with him on the album titled Ornette!. But by the summer of that year he was back in his regular place with the Evans trio, playing a summer engagement in a 7th Avenue South basement club that produced two live albums which had an extraordinary impact on jazz: Waltz for Debby and Sunday at the Village Vanguard.

Together with two studio sessions, Portrait in Jazz and Explorations, these albums effectively turned the piano trio from “piano with rhythm accompaniment”, as it used to say on the labels of 78s, to three-way exchanges between creative equals, with the drummer Paul Motian as the third voice. Booker Little, with whom LaFaro recorded in 1960, described him admiringly as “much more of a conversationalist behind you than any bass player I know.”

Little died of uraemia in October 1961, aged 23. Three months earlier, three days after appearing with Stan Getz at the Newport Jazz Festival, LaFaro had died in an accident while visiting family in upstate New York, seemingly after falling asleep at the wheel. Both were prodigies, serious-minded young musicians equally determined to avoid the traps set by the jazz life, with golden creative futures ahead of them. (LaFaro had just begun to compose, and the legacy of the Evans trio to jazz impressionism is unthinkable without his only two recorded pieces, “Jade Visions” and “Gloria’s Step”.)

There were great bass players in jazz before LaFaro. Some of them — Jimmy Blanton, Oscar Pettiford, Ray Brown, Charles Mingus, Ray Brown, Red Mitchell — helped to change how the instrument was played, just as Coleman Hawkins or Charlie Parker changed the saxophone and Louis Armstrong or Miles Davis changed the trumpet, in ways that no classical player could ever have imagined. So when LaFaro arrived on the scene at the end of the 1950s, in his early twenties, he was firmly in a tradition of extending and influencing an instrumental vocabulary.

In the biography, many musicians describe the shock they felt at his death and try to describe what it was that made him so remarkable: the way that he took such a big step in helping to free the bass from the subservient role of walking a steady 4/4 at whatever the tempo might be. Gary Peacock, another friend and contemporary, who later took on his mantle with the trios of Evans and Keith Jarrett, describes him as “anchoring the time without playing it”.

That’s a beautiful way of explaining his effect, and it ties in with a simple but very telling observation made by the bassist and educator Phil Palombi in an essay on LaFaro’s playing included in the biography: “LaFaro rarely began a phrase on the downbeat of a bar.” He avoided the obvious, playing games with symmetry, leaving space for others (and for silence), created a feeling of suspense and suspension, mobilising the music and making it float in new ways. Evans and Motian were his willing and brilliant accomplices, but he was the one who set the tone and made it happen.

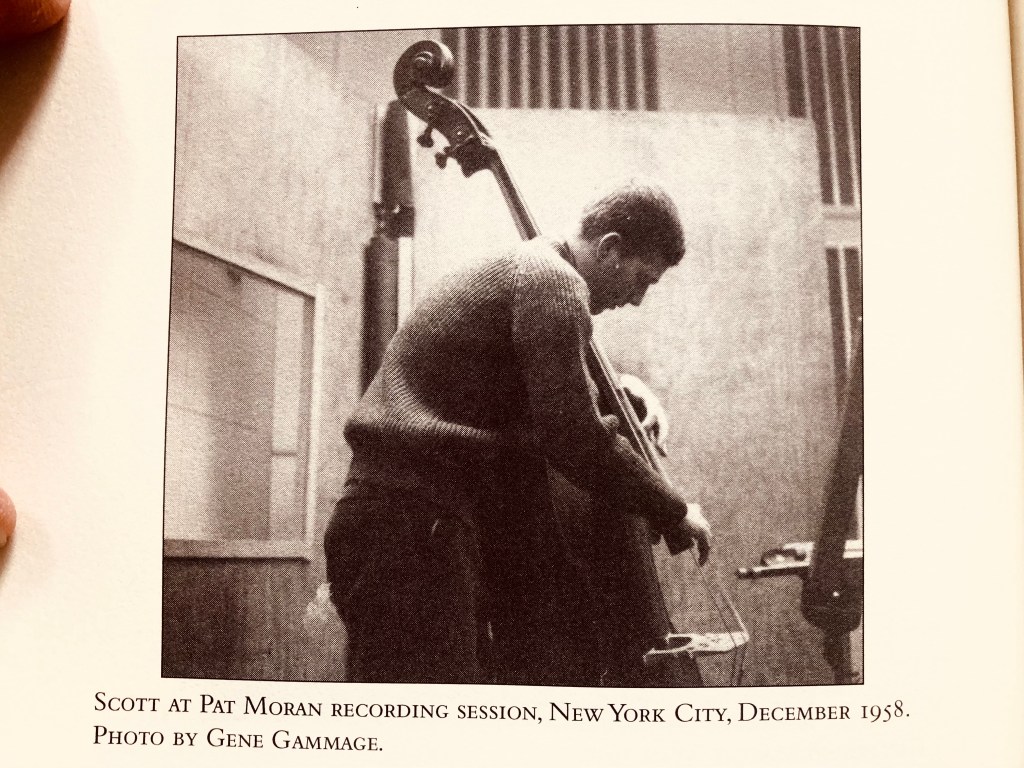

He played a three-quarter size bass built around 1825 by Abraham Prescott of Concord, New Hampshire, found for him in Los Angeles by Red Mitchell. Another great bass player, George Duvivier, helped him to get it rebuilt in New York. (Badly damaged by impact and fire in the fatal car accident, it was completely restored 20 years later.) The height of the bridge was adjusted to lower the action and LaFaro was a pioneer in the technique of plucking the strings with the index and second fingers of his right hand, like a finger-picking guitarist, giving him the ability to articulate phrases of great complexity.

The new set of CDs includes some beauties, such as a couple of cool-as-a-breeze tracks by a sextet co-led by Getz and the vibraphonist Cal Tjader with Billy Higgins on drums, Paich’s characteristically intriguing and beautifully swinging arrangement of “It’s All Right With Me” as a bass feature, a lovely version of “Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams” by a Hawes-led quartet with Harold Land on tenor, and the whole 37 minutes of “Free Jazz”. “Gloria’s Step” and “Jade Visions” are there, as are other Evans classics, including “My Man’s Gone Now” and “My Foolish Heart”.

There’s the occasional oddity, like John Lewis’s arrangement of his classic “Django” for a group including Evans, the guitarist Jim Hall and a string quartet. There’s a version of Dizzy Gillespie’s “BeBop” from The Arrival of Victor Feldman in which Feldman, LaFaro and the drummer Stan Levey flail away at a tempo of 96 bars per minute (that’s bars, not beats), making it to the end without having achieved anything beyond a demonstration of youthful ambition and athleticism (and one that the session’s A&R man, Lester Koenig of Contemporary Records, should have quietly binned).

Out of everything I’ve ever heard of LaFaro’s work, my favourite piece is the Evans trio’s Village Vanguard recording of “Milestones”. Miles Davis’s modal tune received a flawless and historic interpretation when the composer recorded it in 1958 with a sextet (the Kind of Blue band with Red Garland on piano and Philly Joe Jones on drums), but Evans, LaFaro and Motian re-examined, dissected, anatomised and reassembled it in a completely different way.

Curiously, it’s not included in the new set. So here it is. One masterpiece fashioned from another. LaFaro in full flow. Animating and driving the conversation. Rhythmically, melodically, harmonically and conceptually astonishing. Each note changing the one before it. And, in some weird and inexplicable way, only enhanced by the random guffaw from an audience member with which it concludes.

* The Alchemy of Scott LaFaro: Young Meteor of Bass is released on September 20 by Cherry Red. The biography, Jade Visions: The Life and Music of Scott LaFaro by Helene LaFaro-Fernández, was published by University of North Texas Press in 2009 and is the source of the photograph above, taken by the Pat Moran trio’s drummer, Gene Gammage.

Eight years ago I was fortunate enough to be at the Blue Note in Greenwich Village to hear Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra on the night of the US presidential election, and then again the following night after it had been confirmed that Barack Obama would be serving as America’s first black president. The anxious optimism of the first night and the joy and relief of the second could hardly have formed a greater contrast with the current mood of the world, in which the orchestra — minus Charlie, who died two years ago, and now directed by his long-time collaborator Carla Bley — arrived in London to play at Cadogan Hall as part of the EFG London Jazz Festival.

Eight years ago I was fortunate enough to be at the Blue Note in Greenwich Village to hear Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra on the night of the US presidential election, and then again the following night after it had been confirmed that Barack Obama would be serving as America’s first black president. The anxious optimism of the first night and the joy and relief of the second could hardly have formed a greater contrast with the current mood of the world, in which the orchestra — minus Charlie, who died two years ago, and now directed by his long-time collaborator Carla Bley — arrived in London to play at Cadogan Hall as part of the EFG London Jazz Festival.