This is a piece about the bassist Albert Stinson (1944-1969). It’s something I’ve been meaning to write for a long time. The great drummer Jim Keltner was kind enough to talk to me about his boyhood friend, as was another drummer from Los Angeles, Doug Sides, who toured and recorded with him in John Handy’s band. I first heard Stinson in 1963 on Passin’ Thru, Chico Hamilton’s very striking Impulse album, recorded when the bassist was all of 18 years old. To my 16-year-old ears, he was exceptional even then; goodness knows what he might have become.

It’s the evening of Friday, April 7, 1967 in the Harmon Gymnasium at the University of California, Berkeley. Your name is Albert Stinson, you play the double bass, and you’re about to deputise for Ron Carter in what might be the greatest small jazz group of all time: the Miles Davis Quintet as constituted between the autumn of 1964, when Wayne Shorter arrived to join Davis, Carter, Herbie Hancock and Tony Williams, and the middle of 1968, when Carter became the first to leave. The greatest? Certainly the one applying new levels of freedom and near-telepathic interplay to the business of improvising on tunes.

So this group has been together and constantly evolving for the best part of three years and you’re being dropped into the middle of it. You’re only 22 years old but you’re ready, in the sense that you have the chops and the experience. You were a prodigy, and you’ve played alongside Charles Lloyd and Gábor Szabó in a brilliant Chico Hamilton Quintet, and with other heavyweights.

But to play in this band, at this stage, you had to be ready for anything. Accelerando or ritardando, not always synchronised. Stopping on a dime without warning, restarting at the merest twitch of a nerve-end, intuiting the leader’s moves but following without following, waiting out a silence, hitting the short, sharp ramp from triple-p to triple-f without a moment’s doubt. Playing against or through what someone else was doing.

You’re not the first bassist to deputise for Carter, a busy guy on call for many sessions. Gary Peacock was the first. Then Reggie Workman, then Richard Davis. After you, there’ll be Miroslav Vitous before Carter goes for good and Dave Holland becomes a permanent member. All great, great bassists. And now it’s your turn.

There’s a buzz in the Harmon Gymnasium. For starters, Miles calls “Gingerbread Boy”, the brusque, flaring Jimmy Heath tune featured on Miles Smiles, the quintet’s second studio album, the one that made everyone realise something different was happening here. At a rocket-propelled 80 bars a minute, the theme hurtles past, with Williams’s drums at their most volcanic. You play time, straight. You survive, although you miss the cue at the end and the piece finishes with your phrase trailing off, as if surprised by the sudden silence around you.

Miles leads into “Stella by Starlight”, his tone at its purest, the trumpet holding a long note into what feels like infinity as you join Hancock in a free background that seems to be inventing itself outside the tune. Eventually you move into a walking medium 4/4, deploying your big, strong tone but keeping the elasticity that enables you to move with the others when the tempo doubles and Williams starts to force the issue. You’re okay, and a little more than that when you respond to the wind-down of Shorter’s solo with something that shows you’re getting the hang of this particular freedom of narrative. Hancock’s solo begins out of tempo and you invent figures to support him before you slide back into the 4/4, seamlessly.

And then, on Shorter’s “Dolores”, a post-bop epigram also from Miles Smiles, the tempo goes back up, and now you’re no longer feeling your way but fully contributing, the equal of these four giants as they charge through a warp-speed exercise in musical plasticity, in aural geometry, in listening, hearing and responding at some Zen level of intuitiveness. In fact you’re almost too ready when Miles creates the silence from which he goes into “Round Midnight”, and you let your lower-register notes bloom in a way that Carter would probably consider excessive. But you’re part of the excitement as Williams’s snare-drum fusillades overwhelm the two-horn fanfares and soon you’re shifting the time around behind the flickering, nudging phrases of Shorter’s solo.

And now you’re home, riding the waves as the set continues with something based on the bones of “So What” and concludes with “Walkin'”. After just under an hour, it ends with an ovation.

—ooOoo—

“Albert brought something different to that band,” the drummer Jim Keltner told me when I asked him to talk about his longtime friend. “Ron Carter is one of the greatest musicians ever, but Albert brought a different kind of fire. They were so highly evolved, and Albert was one of them. I don’t really want to talk about genius-this and genius-that, but I do believe that he was a genius. He came back and told us that Miles had asked him to join the band, but he said he couldn’t because he had too many gigs lined up with Chico. That’s mind-boggling. But it’s the kind of player and person he was.”

Keltner, who would go on to play with Bob Dylan, John Lennon, George Harrison, Ry Cooder, Neil Young and countless others, was in his last year at the mostly white Pasadena High School when he met Stinson, who was two years younger and attending the mostly black John Muir HS. They were neighbours in the Altadena. “I was always aware that I was older than Albert,” Keltner said, “but I knew that I would never be as smart as him. A very, very smart cat. A very high IQ.” Another neighbour, the vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson, had just graduated from John Muir, and the three played together constantly.

“Albert lived in a kind of cul-de-sac about five minutes from my house. It was a very diverse community, very well integrated. White people had black or Asian neighbours, and there were a lot of Mexicans around. And I’m half-Mexican.”

He remembered that Stinson lived with his mother, a former dancer, and her steady flow of boyfriends. His father had left the family early. When Keltner got married young, to a girl he’d known in high school, Stinson envied him. “He always loved the fact that Cynthia, my wife, and me, we made the long haul, which is very unusual for musicians. I think he wanted that and thought he could have it, but it wasn’t to be. I can’t really bring myself to talk about his personal life, but he was hurt badly by his relationship. His very first girlfriend was really young, a young beautiful black girl, and he was young, too… he was in love with her. I can’t speak for her but he was really in love with her. They were a little team. At some point he married and had a baby. He’s called Ian Stinson. He looks just like Albert, but with dreads… a beautiful kid. He’s a drummer and lives up north.”

Keltner remembered an early visit to the Stinson house on Shelly Street. “One afternoon I went over and he was sitting on the floor with his cigarette and ashtray and his weed and a little half-smoked doobie and a glass of cheap Ripple white wine, with a newspaper and glue and a huge massive book. He was making his own bass from a library book. I’m not sure how he did it, but the bass that he built himself was the one that I used to put in my car, because I would drive him everywhere. An upright bass and my drums in a Volkswagen.”

But before long they’d all hooked up with another young star of the future, the saxophonist and flautist Charles Lloyd. “I told Charles Lloyd about Albert when we were driving down from a little gig in a country club up in the mountains,” Keltner said. He was subbing for Mike Romero, Lloyd’s regular drummer. Hutcherson was already in the band, along with the pianist Terry Trotter and the bassist George Morrow. Soon Stinson would be replacing Morrow and also persuading Keltner, who thought he would never be as good as Romero, out of giving up music altogether.

“Mike Romero would come into the music store where I worked and I just thought he was the coolest guy in the world. One day he said to me, ‘You want to sub for me for half a set?’ I acted very confident and yet I was scared shitless. So I played, then I stayed and watched Mike, and I was so demoralised. Albert lit into me and told me how dumb I was. He said, ‘I would rather play with you any day than with Mike Romero.’ I said, you’re just saying that because you’re my friend. But I never forgot it. It carried me through.”

Of Stinson’s six albums with Chico Hamilton, recorded between 1962 and 1965, Passin’ Thru is the one that made a deep impression on me at the time. On pieces like “Lady Gabor” and the title track, he seemed to have metabolised the deep-groove drone effects created by the multiple bassists on such John Coltrane recordings as Olé and Africa/Brass. Barely 18, his strength and maturity were extraordinary.

He’d also recorded for Pacific Jazz with the pianist Clare Fischer (Surging Ahead, 1962), the guitarist Joe Pass (Catch Me!, 1963) and Charles Lloyd (Nirvana, 1965). He’d played (although not recorded) with Gerald Wilson’s mighty big band in Los Angeles. In 1964 he’d visited London with Hamilton, Szabó and the altoist/flautist Jimmy Woods to record the soundtrack for Roman Polanski’s Repulsion. He’d been in Rudy Van Gelder’s famous studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, one day in 1967 to record a quartet session for Blue Note under Hutcherson’s leadership, with Hancock on piano and Joe Chambers on drums, featuring a fantastic Stinson solo on a piece called “My Joy”, although the album wouldn’t be released until 1980, under the title Oblique.

“Albert loved playing music and he loved jazz,” Keltner said. “He was a thorough jazz musician. All of our friends, jazz players, were completely inspired by him. He was a leader, a ringleader. I was always round at his house, listening to music. We listened to Bartók, we listened to Coltrane. Everything I heard, I heard it first with Albert. Bobby Hutcherson lived even closer to him than I did. Those 3 a.m. calls to rescue Albert, it was always Bobby and me who went to save him.”

Those 3 a.m. calls came when he’d overdosed on heroin, something that had existed in his life alongside music well before, in 1967, he, Hutcherson and Keltner joined the band of the altoist John Handy, whose reputation had been made by an incendiary performance at the 1965 Monterey Jazz Festival. “Albert got me that gig,” Keltner said. “It was a fantastic time for me. It was at a club in San Francisco called the Both/And. I don’t remember playing very good, just hanging on and trying to get it right. I didn’t have the confidence. Jazz playing is a huge amount about confidence. Not like rock and roll, where you do your thing. Not that I’m belittling it. But jazz is a different thing. And even though I wasn’t cutting it, and I knew it, Albert would make it right.”

By the time the new line-up made a well received album, New View, recorded live at the Village Gate in New York for Columbia, featuring a wonderful version of Coltrane’s “Naima”, Keltner had been replaced by Doug Sides, another young musician from Los Angeles.

“Albert was one of these kids who just had a glorious talent, and he was a person that almost anybody would love,” Handy told David Brett Johnson, a deejay on Indiana University’s radio station, in 2008. “A very easy, sweet young guy, and his playing was just incredible. He seemed to have a bunch of natural ability, which I understood because I came that way myself, without that much experience, but just kind of knew how to do it. However, I was afraid — even with those guys in my band, there were drugs. They kept it away from me. They were younger, they kind of… you know, when you‘re the bandleader the little cliques kind of take place, and they weren‘t vicious, they just… I could see the half-generation difference in age and all.”

Doug Sides, who moved to the UK in 2010 and died at his home in Kent this month (October 2024), aged 81, remembered meeting Stinson at jam sessions in an LA place known as the Snake House — actually the home of a musician who kept pet snakes.

“Albert a very special human being,” he told me. “He was one of the nicest guys I ever met. He didn’t have animosity toward anybody. He just liked to have fun. But he had one problem. He liked to get high and he liked to shoot up with the junkies. And he tried to keep up with them, which caused him to overdose a few times before he died in New York doing the same thing.

“He was a really great player. He had a big sound, too, and he could play any tempo. For a small cat – he was short – but he was very strong, strong like somebody who was 6’5 or something, he had that kind of strength. In those days they had beer cans that you couldn’t crush very easily, not like the modern ones where you just squeeze and they fold up. He used to crush them like they were the modern ones.”

His seven months with Handy included a stint in San Francisco performing an opera, The Visitation, written by Gunther Schuller for 19 voices, woodwind and string sections and a jazz quartet, applying ideas from Kafka’s The Trial to the world of civil rights in America, and blending 12-tone composition with jazz.

“Albert had never played with a conductor,” Handy told David Brent Johnson. “Well, man, he learned those parts by just — with one or two rehearsals, and they were very difficult, as you can imagine if you know anything about Gunther Schuller‘s music. And at one point Gunther Schuller stopped the rehearsal and said to the bass players, ‘Do you hear this bass player? He sounds as big as almost all of those guys put together back there!’ And poor Albert was so sick, I didn‘t realise it, from doing crazy things, you know, and vomiting during the breaks because he was taking drugs… I didn‘t know that. He kept it away from me. All I know is he played his butt off.”

Jim Keltner said he thought one of the reasons Stinson turned down Miles Davis’s offer was that he didn’t want to leave Altadena, where his mother had left him their house on Shelly Street. “My own life had really changed by that time,” the drummer recalled. “I’d done rock and roll with Gary Lewis and the Playboys in 1965. Albert thought that was cool. He wasn’t judgmental. Some of the others were jazz snobs. By 1968-69 I was playing in a couple of bands and Albert was travelling more so I was seeing him less, but I’d hear things.”

Stinson joined the band of the guitarist Larry Coryell, whose popularity had taken off during his time with Gary Burton’s quartet. “When I heard he’d joined Coryell,” Keltner continued, “someone said he was playing electric bass, or thinking about it. I thought, oh wow, that’s incredible. He’ll burn that thing up. He’ll make it his own and he’ll be one of the baddest cats and maybe at some point we’ll play together again. But then, bam.”

On the road in June 1969, a few weeks short of his 25th birthday, Stinson overdosed again in a New York hotel room. This time he would not be saved. “It wasn’t a shock,” Keltner said, “but it was incredibly sad. Then I started hearing stories about the guys he was getting high with. Instead of trying to save him, they got scared and ran away. That’s one of the things I learned in the earlier days, one of the sad, dumb things, about how you don’t do that. You’ve got to save them. Which then, in turn, I got saved two times later. Bobby and I weren’t there to save him.

“Because of that rumour, I remember just hating Larry Coryell and everything about him. It was a misplaced anger. I didn’t know the details or anything. Eventually I had to let go of blaming him for Albert’s death.”

Whatever his habits, and the problems they may have caused for himself and others, Albert Stinson was someone who inspired powerful feelings of love and loss in fellow musicians. In Keltner and Sides, obviously, and also in Charles Lloyd, who cherishes his memory. Four months after Stinson’s death, Bobby Hutcherson wrote and recorded a lament called “Now”, dedicated to his late friend, with a lyric by Gene McDaniels delivered by the soprano Christine Spencer: “At the end, no more need…”

“Later in life,” Keltner told me, “I came to appreciate that although people will compliment you on your talent, generally speaking your talent is based on who you’re playing with. Every time I played with Albert, under any situation, whether it was some little silly gig like a bar mitzvah or whatever, it was incredible. It was always great. I always felt like I was somebody.

“It shows how amazing Albert was. He was so soulful. And he was too sensitive a cat for the world. A sensitive, beautiful old soul.”

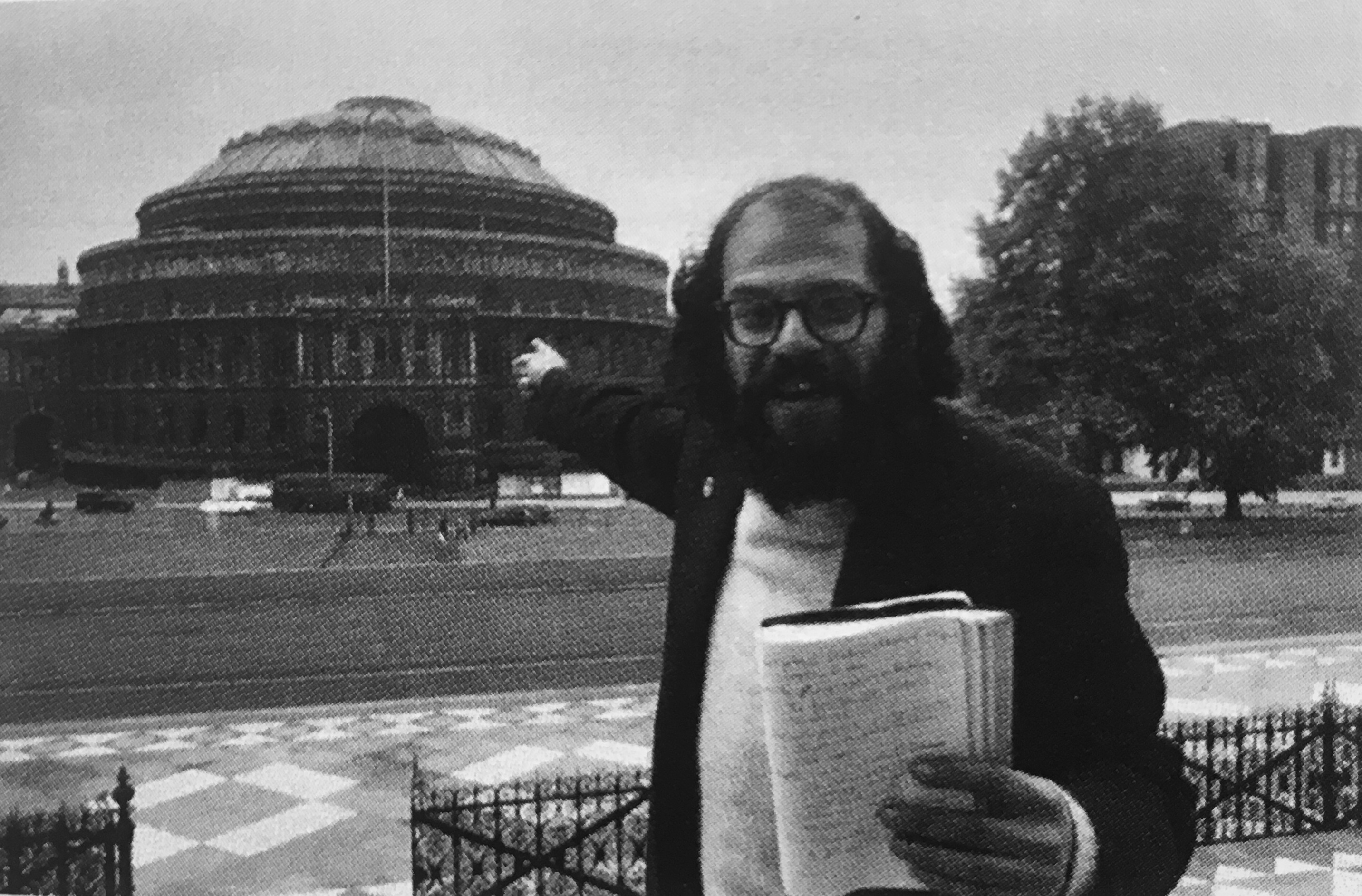

* The fine photograph of Albert Stinson is by Ave Pildas, whose work in jazz and many other fields can be seen at http://www.avepildas.com. A bootleg of the radio broadcast of the Miles Davis Quintet’s Harmon Gymnasium concert was released on a CD some years ago by the recordJet label.

With three hours to go until the inauguration of Donald J. Trump as the 45th president of the United States, the coffee shop I frequent was playing the Staple Singers’ “Respect Yourself”. That’s a record with a lot of American history in it, one way and another: a message delivered by a mixed group of black and white singers and musicians, showing how music can provide encouragement, comfort and even guidance.

With three hours to go until the inauguration of Donald J. Trump as the 45th president of the United States, the coffee shop I frequent was playing the Staple Singers’ “Respect Yourself”. That’s a record with a lot of American history in it, one way and another: a message delivered by a mixed group of black and white singers and musicians, showing how music can provide encouragement, comfort and even guidance. There was a time, seven or eight years ago, when I came to the conclusion that Bill Frisell was simply making too many records. I fell out of the habit of automatically buying his new releases because he seemed to be spreading himself too thin. Good Dog Happy Man (1999) and Blues Dream (2001) are still two of my all-time favourite albums, but I tend to prefer him nowadays as a contributor to other people’s records — something to which his particular expertise is well suited. Used sparingly, the characteristics of his playing add texture and flavour, just like King Curtis or Steve Cropper once did.

There was a time, seven or eight years ago, when I came to the conclusion that Bill Frisell was simply making too many records. I fell out of the habit of automatically buying his new releases because he seemed to be spreading himself too thin. Good Dog Happy Man (1999) and Blues Dream (2001) are still two of my all-time favourite albums, but I tend to prefer him nowadays as a contributor to other people’s records — something to which his particular expertise is well suited. Used sparingly, the characteristics of his playing add texture and flavour, just like King Curtis or Steve Cropper once did.